By this time next year, it’s not entirely implausible that Donald J. Trump will be occupying the White House or, as he’ll likely rechristen it, Trump 1600. In which case, it won’t be too much longer till Mexico is separated from us by a huge wall. Then there’s Canada as a go-to destination, but for Americans looking to put a little more distance between themselves and President Trump, there are a wealth of other escape plans. About 7.6 million compatriots are already living abroad. Some go where their work takes them; others find they can work from anywhere with a good Wi-Fi connection — so why not choose a locale with a low cost of living and a thriving expat community? The U.S. also makes it relatively cheap and easy to live overseas. “You don’t have to return to the country on a regular basis to maintain citizenship,” says Muzaffar Chishti, director of the Migration Policy Institute’s office at the NYU School of Law, which cuts down on the trips back home. And you can vote absentee in 2020, if voting is even still a thing then.

The work-from-anywhere entrepreneurs of Ubud, Bali

The Dossier

The Expats

So-called location-independent entrepreneurs, running their companies in between yoga sessions and New Age retreats.

The Lifestyle

Jam aret, which translates as “rubber time,” rules on the island. Ubud, the cultural capital of Bali, is 33 miles inland and less party-focused than the beach towns.

Rent for a One-Bedroom

$400 a month for a 430-square-foot home.

Getting There

Most come under tourist visas and keep their income off the books.

Their clubhouse is a co-work space.

Open air, not open office.

“The expat community here is tight, and conversation gets real quickly. Plus, there’s a New Age–y vibe so people feel safe sharing. My girlfriend and I are finishing a book on our three-month wine-tasting journey. I write and work on my YouTube channel from the co-work space Hubud. Yesterday, at a social event there, I was eating with a Belgian user-experience consultant who just met his girlfriend, a kinesiologist-coach, in Ubud.” —Matthew Horkey, 33, CEO and founder of Exotic Wine Travel. Nationality: American. Arrived: January 2016.

It’s like a cheap San Francisco, with better weather.

The extracurriculars are even the same.

“I rise, meditate, exercise, email, [have] client meetings, podcast, yoga, sleep, repeat. I also join the Bali Hash House Harriers, a running-and-drinking club that does a hike every Saturday through places you would never see as a tourist. Rain or shine they go, threading their way through rivers and little villages.” —Gary Dykstra, 45, founder of consensusreality.io, a Bitcoin consultancy. Nationality: American. Arrived: February 2012.

“I wake up to the sounds of birds; meditate or do yoga; order my raw organic green juice or turmeric jamu, a medicinal juice, from Wayan’s Coconut Juice Bar; work from my house, a café, or the pool. There’s more going on here than when I was living in San Francisco. There’s even an improv-comedy troupe.” —Monica*, 38, founder of a sleep-mask manufacturer. Nationality: American. Arrived: August 2013.

*A pseudonym requested to protect her visa status.

What They Miss

“Amazon.com. Customs here is a racket.”

“If you ask someone to fix the air conditioner, they say they’ll come but don’t arrive for a few days … if ever.”

And the wine’s good, too.

One local’s favorite bar.

“I like to have wine at a bar within the restaurant Bridges. It won an award for excellence from Wine Spectator.” —Horkey

The fast-paced businesspeople of Shanghai, China

The Dossier

The Expats

M&A men, ad execs, and lifestyle consultants.

The Lifestyle

Noisier and busier than nearly anywhere else. Non-Mandarin-speakers, however, lead a relatively cloistered existence.

Rent for a One-Bedroom

$1,500 a month for a 650-square-foot apartment near the center of Shanghai.

Getting There

Provided you’ve got a job, go for it. But the Chinese government is quite strict when it comes to immigration.

The French Concession is an expat hub.

One local describes the view from his office window.

“My office is in a former French Concession lane house. I see a three-story building opposite me built in the 1930s with ramshackle roofing. There are two bamboo poles and a clothesline stretched between them on the upper floors. Overcoats, overstretched old women’s underwear full of holes, and pajamas are drying right next to a chicken carcass and a chunk of fish on the bone, which is a pretty common sight in colder months.” —Andrew Kuiler, 40, owner and managing director of the Silk Initiative, a food-and-beverage consultancy. Nationality: Australian. Arrived: September 2010.

What They Miss

“Gyms that are open late.”

“Decent potato chips.”

“Big skies.”

Where They Go Out

“My favorite restaurant right now is Xixi, a great little Italian-owned fusion-Chinese bistro, with great mash-ups such as pumpkin-and-pine-nut dumplings.” —Kuiler

The Connecticut of Shanghai.

Foreigners congregate in the suburbs.

The outer suburbs of Shanghai like Jinqiao, with their walled villas and international schools — which Chinese nationals are forbidden to attend — could pass as Wilton, Connecticut. “The only Chinese you meet are cleaners and guards,” says Kate Lorenz, a relocation specialist. That’s in contrast to Shanghai proper, where the younger set congregates on Yongkang Lu, a strip of bars in the French Concession that looks like Bourbon Street.

Expat versus local isn’t really a thing.

So long as you speak Mandarin.

“The differentiation of expat versus local is outdated. They’re both such fragmented groups. You’re more likely to see divisions among industry and stage of life than among nationality or origins. Assuming, that is, you can get past the language barrier. Two young people who are working together in architecture — one local and one foreign — are much more likely to know each other than two randomly selected expats. That being said, people are much more direct here than in England. It was a shock being told up front I had gained weight in the casual coffee breaks.” —Alex Ditchfield, 31, vice-president of BDA Partners, a mergers-and-acquisitions firm. Nationality: British. Arrived: September 2008.

But the Chinese Communist Party’s rule is.

Especially on the internet.

“On a positive note, central planning makes things happen overnight. But it’s frustrating at work when you need to use VPNs to access relevant information. But even then, sometimes not being on Facebook and Twitter can be a good thing. I realize my life is in many ways richer because I am not so distracted by social media like most friends back home or in the States.” —Kuiler

“It’s a city of contradiction. The Chinese always seem to find the noisiest way of communicating, and that’s on top of the nonstop renovation and construction. You go over there and it buzzes. And yet you have these pockets of quiet, which are very confusing.” —Kate Lorenz

The intrepid journalists of Beirut, Lebanon

The Dossier

The Expats

Reporters who use the city as a convenient home base for covering mena—their acronym for the Middle East and North Africa.

The Lifestyle

First World nightlife and Third World infrastructure plus the frisson of war-zone adjacency.

Rent for a One-Bedroom

$460 for an 860-square-foot ground-floor unit in Achrafieh, one of the oldest and most popular neighborhoods.

Getting There

A one-month tourist visa can be obtained at the Beirut airport; apply for a second and third month at the Sûreté Générale once in Lebanon.

The work-hard-play-hard ethos is the draw.

Plus, it’s relatively safe, for the region.

“I was in D.C. before this. Beirut is a more dynamic atmosphere. There’s more fieldwork and more interaction with locals. Beirut doesn’t feel dangerous on a day-to-day level, though after the bombings in 2013, I was tentative about walking in public areas: public squares, main roads, downtown Hamra — basically anywhere that wasn’t on the back roads.” —Justin Salhani, 28, journalist. Nationality: Lebanese-American. Arrived: August 2010 (returned to D.C. last year).

What They Miss

“Heating in winter.”

“Cheap sushi.”

“Municipal services that work and politicians who understand that these services are a pretty basic part of governance.”

About Those Municipal Services …

“The electricity problems keep on getting worse, but now we have water problems, too. We’ve been in the middle of a garbage crisis for the past eight months, and there’s a vast Syrian-refugee community here that is not being cared for.” —Bryan Denton, 32, photographer. Nationality: American.

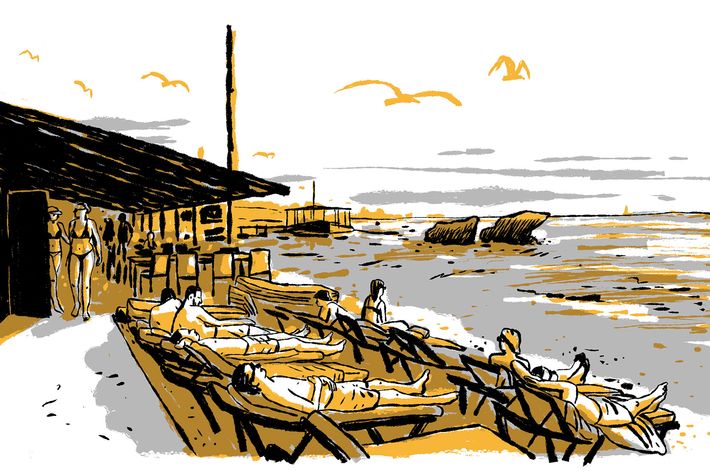

The homes away from home.

Bars, meet-ups, and the sea.

Expats congregate at bars in Mar Mikhael and Hamra like the Captain’s Cabin. The Foreign Press Club also holds the occasional barbecue. In the summer, private beach clubs like Pierre and Friends offer sailing.

“Like an aging playboy.”

One take on the city’s two sides.

“Beirut is a place of chaos and hedonism. It’s like an aging playboy: He is a bit too proud of his past achievements, talks a bit too much about what it was like when people still called him the Paris of the Middle East. Considering the countries around him are mostly authoritarian, racist torturers, Beirut is a pretty good place to be. Infrastructure, though, is a nightmare. The internet is terribly slow. We have to hire a private water company. There’s a traffic jam all day, starting at 7 a.m. On the other hand, you can go out every night and find a drink somewhere. Lebanese women walk around in the most insane high heels on pavement that hasn’t been reconstructed since the Civil War, which ended in 1990. I like that mix.” —Theresa Breuer, 29, freelance journalist. Nationality: German. Arrived: January 2015.

A breakdown of the expat social hierarchy.

The old-timers tend to stick to themselves.

“As a westerner, you’ll always be an ajnabi — a foreigner. That doesn’t mean people won’t accept you, but it’s a permanent outsider status. You’ll always be looking in. The foreign-press community is made up of several generations. Those of us who’ve known each other for the last decade are pretty close-knit. We number around ten or so. It’s a diverse group that is constantly evolving but has a strong core. There are also a lot of younger journalists starting out, recent arrivals who’ve been here for a year or so. Lots of them arrived when Egypt started to get too dodgy to work in as a freelancer.” —Denton

“The Lebanese bitch about the catastrophic infrastructure but with a cigarette in one hand and a Champagne cocktail in the other.” —Theresa Breuer

*This article appears in the March 21, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.