There are countless iconic photos of Muhammad Ali, the boxing icon and cultural colossus who passed away last night at the age of 74 — training with children in Africa, celebrating over a flattened Sonny Liston, or holding his fighting pose so gracefully underwater. But a key image to hold in the mind when trying to understand Ali is the red-and-white Schwinn bicycle that he lost in 1954.

The bike started his career. The exact model is unknown — the Schwinn catalog ranged from the Phantom (“Nothing In The World Like It! The Most Beautiful Bike You Can Own!”) to the Panther (“Outstanding combination of deluxe features!”) — but a likely candidate is the Spitfire, described as “a wise choice” in situations “where price is important.” The Spitfire didn’t feature the leather saddle or chrome of more expensive models, but that wouldn’t have mattered to young Cassius Clay, as he was known then: the bike was new, it was his, and it was a first taste of freedom, a chance to explore his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky without his parents.

In October of that year — the month when Willie Mays made “the Catch” for the Giants in the World Series and a time when black athletes were entering professional sports for the first time — Clay and a friend were riding around Louisville. According to David Remnick’s telling in “King of The World,” they went to a convention of local black merchants at the Louisville Service Club in search of the free popcorn and ice cream the vendors doled out.

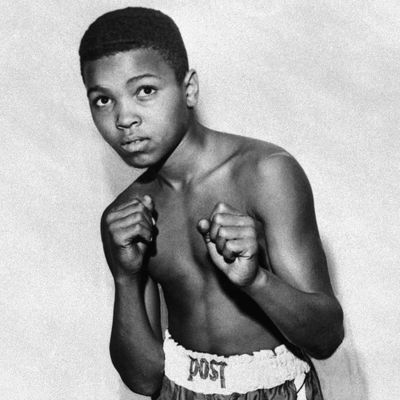

Twelve-year-old Cassius wanted to show off his new bike and went back outside to check on it, but the Schwinn had vanished, and with it his pass to adolescent freedom. He started to cry. Consoling him, a man told the young boy to talk to a police officer in the basement of the building, where a boxing gym had been set up.

Consumed with anger, Clay went downstairs, where he met Joe Martin, a local officer who taught boxing to troubled kids as a means of instilling discipline. Martin listened as the young boy fumed about finding the kid who stole his bike and beating him up. Even then, he was full of ideas of punishment and justice.

“Well,” Martin said, “do you know how to fight?”

“No,” Clay said, “but I’d fight anyway.”

Martin gave the young boy his first offer, and test: free boxing lessons. Clay passed the first test when he showed up at the gym, and the second when he returned.

Boxing was not the only allure of Martin’s basement: There was also notoriety. Martin had a deal going with a local television station, who broadcast local bouts for a show called “Tomorrow’s Champions.”

Cassius Clay couldn’t resist. After six weeks of training, he was scheduled for his first fight. The bout was a three rounder. The weight: 89 pounds. Clay and his opponent, Ronnie O’Keefe, flailed away at each other with massive gloves until the final bell rang.

Clay seized the spotlight. At 12, he revealed his incredible skill for showmanship for the first time and announced to the crowd that he’d be “the greatest of all time.”

The judges weren’t convinced yet. He’d won, but via split decision.