The Good News at the Washington Post, Trump’s Least-Favorite Paper

Jeff Bezos, journalism’s white knight.

–&–

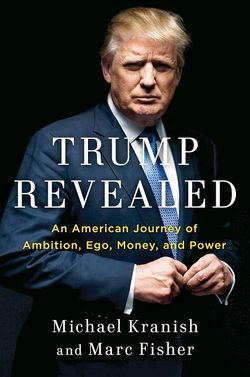

Donald Trump banned.

One of the first things you notice in Washington Post editor Marty Baron’s office is the typewriter art on the wall. “To me, they represent a bit of a metaphor,” he says one afternoon in May, standing in front of a cheerful Anne Duncan lithograph of an Underwood typewriter done in a riot of red and magenta. “These were the glory days of the old newspaper,” Baron explains. “And this” — he gestures at a muted photograph of a typewriter’s fire-charred skeleton taken by a Post photographer on assignment in Detroit — “is some of the wreckage of the industry. That’s kind of where we are.”

And yet Baron does not seem at all worried. “I feel quite good about things, actually,” he says, sitting across from a cutout of an Oscar statuette he’d received from colleagues for being the real-life hero of last year’s Academy Award–winning film Spotlight, about his time at the Boston Globe. Baron’s optimism has little to do with his Hollywood turn and a lot to do with editing the Post at a time of resurgence under new owner Jeff Bezos. In 2013, the Amazon founder bought the paper for $250 million from the Graham family. Since then, he’s invested millions more, turning the Post into a laboratory for inventing a sustainable future for newspapers.

In January, Bezos moved the paper out of its drab offices atop a former printing plant and into a sleek space on K Street that resembles a tech start-up. Around the newsroom, engineers and data scientists sit alongside journalists to integrate emerging technologies into everything the Post does — a far cry from the old Post, where, until 2010, the digital newsroom was relegated to a separate building all the way across the river in Arlington. “We view ourselves as a technology company as well as a media company,” says Post publisher Fred Ryan. It’s a phrase that has become something of a mantra for web publishers lately (Vox Media, Gawker, and BuzzFeed, among others, have claimed the same, and the Tribune Publishing Co. rebranded itself, somewhat ridiculously, as TRONC — “Tribune online content”), but the Post is in a singular position: None of those other companies is owned by someone who also built one of the most significant companies of the modern internet.

Journalists are inclined to be suspicious of the tech industry, which, after all, upended their own in a fairly painful way. And Amazon in particular hasn’t traditionally engendered much goodwill with bookish types. But the tech world does come with deep pockets and a new way of looking at old problems. “What Jeff really brought, beyond his initial investment, is more freedom to innovate and take more risk,” says Joey Marburger, the Post’s director of product.

After years of layoffs, buyouts, and battered morale, the Post’s newsroom has its swagger back. Under Bezos, the paper has grown by 140 journalists and has won two Pulitzers. Its aggressive coverage of the 2016 presidential race frequently drives the news cycle and so infuriated Donald Trump that he has banned its reporters from his campaign. Most significantly, in business terms, since Bezos bought it, traffic to washingtonpost.com has more than doubled. When it briefly beat out the New York Times in November, to celebrate, the Post ran house ads proclaiming itself “the new publication of record.”

Getting journalism in front of readers has always been a priority for newspapers. Web publishing has only increased the stakes. The Times has waded cautiously into the territory of “audience development,” worrying about maintaining a certain Timesian quality. But the new Post has none of these reservations. In an era when readers increasingly get their news on social-media platforms, the Post is the only major newspaper company to publish all of its content directly to Facebook’s Instant Articles. (The Times has declined to publish most of its articles there for fear of cannibalizing its subscription business, which still makes up 60 percent of revenue.) The Post newsroom now talks unabashedly about journalism as a consumer product. “[Jeff] constantly tells us, ‘Don’t focus on the competition, focus on the reader,’ ” says Shailesh Prakash, the Post’s chief technology officer. It’s easy to see parallels between Bezos’s philosophy of growth as developed at Amazon — essentially, give the people what they want, as fast as possible — and the changes at the Post.

Some of that growth has come via tried-and-true web methods: The Post has ramped up the number of first-person essays, along with health and lifestyle coverage (recent stories: “As a Trans Muslim, I Used to Feel Vulnerable All the Time”; “Low Testosterone Makes You a Better Dad”). Headlines, in particular, have gotten webbier and more sensational (“This Is What Happened When I Drove My Mercedes to Pick Up Food Stamps”). The paper has launched a slew of newsletters, like the agenda-driving Daily 202. But Bezos’s open checkbook also means the Post is able to do ambitious (and expensive) journalism — a 7,000-word investigation of a sexual-assault case in the Marines; a multimedia package on the European migrant crisis; extensive reporting on the Syrian civil war.

The paper is also experimenting technologically and collaborating with Silicon Valley to do so. This spring, the Post became the first publication to team with Google to build a prototype of a “progressive web app,” designed to cut mobile page-load times from four seconds to 80 milliseconds and to let readers surf the Post in their browsers even without a web connection. The company is conducting research on intelligent “news bots” with whom readers can chat to get the headlines in their car, on Siri, or (in a convenient bit of synergy) with Amazon’s Echo. Other publications are trying similar things, but the Post has a bigger budget than most to play with.

This might not always be the case if the Post doesn’t eventually turn a profit. Bezos is said to have invested $50 million in the company last year, according to sources. “He wants us to prove ourselves,” says Prakash. As does — in a reversal of the old circulation wars — the rest of the industry, which finds itself rooting for a tech titan to figure out how to disrupt it.

In the very recent past, the Post was a symbol not of possible resurgence in the newspaper industry but of its precipitous decline. In 2008, Katharine Weymouth, the granddaughter of legendary Post owner Kay Graham, was named publisher with a mandate to look for new sources of revenue. One of her ideas — selling lobbyists and advertisers access to Post journalists at off-the-record “salons” — was leaked to Politico, inspiring worry over whether the next generation would be the same careful stewards of the Post’s journalistic integrity as previous ones. The salons never came to be, but neither did any other significant revenue streams: By 2013, with more newsroom cuts in the offing, Weymouth and her uncle, Washington Post Company CEO Don Graham, realized that the best way for the family to protect the Post was to find a deep-pocketed, public-spirited buyer. They drew up a short list of tech-savvy, politically moderate billionaires to pitch, which included Pierre Omidyar, Carlyle Group co-founder David Rubenstein, former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, and Bezos. In past interviews, Bezos has said he wasn’t initially interested in owning a newspaper. But he accepted Graham’s $250 million ask — a bargain price — because he thought it would be an intellectual challenge to try to fix the industry’s broken business model.

The news that the Grahams had sold the Post to the Amazon founder stunned the newsroom. The Grahams had owned the paper since 1933, and despite Weymouth’s rocky tenure as publisher, the family remained beloved by Post employees. And she’d succeeded in recruiting Baron as editor in 2012. Meanwhile, many journalists regarded Bezos warily. He was the CEO of a company famous for its culture of secrecy and hostility to the press. (Bezos declined to comment for this article.) “I feel sorry for my PR guys,” Bezos recently joked at a tech conference.

During his first newsroom meeting, Bezos spoke in the vaguest of terms about his plans. “We need to think big and lean into the future,” he said. And: “The death knell for any enterprise is to glorify the past, no matter how good it was.” He was clearly learning on the job and making some missteps along the way. Bob Woodward recalls how he emailed Bezos in 2014 to ask him to attend Ben Bradlee’s funeral after hearing the new owner wasn’t planning to show. “He was the soul of the institution that is now yours,” Woodward wrote to him. “Understand, on my way,” Bezos replied. In early meetings, Bezos suggested things that baffled and worried senior executives: Once, he floated the idea of creating a game that would allow readers to erase vowels from articles they didn’t like; another time, he asked why Post reporters needed editors at all.

Some of Bezos’s early personnel moves scared employees, too. First he replaced Weymouth, a year almost to the day after taking over (he’d agreed to keep her in her role for a year). In her place, he recruited Fred Ryan, the former president of the parent company of Politico — a publication famous for its grueling newsroom culture. Then Bezos froze the Post-employee pension fund. “Jeff has a Silicon Valley ideology that we don’t do pensions,” one former Post executive says.

By the end of that year, though, the internal view of Bezos’s leadership had improved markedly. He instituted biweekly conference calls with senior executives and scheduled quarterly retreats. Over breakfast shortly after Bezos bought the paper, Woodward — who’d known his new boss socially for years — told him the Post needed to hire 20 new reporters. “I had a list of things I went through, and he took notes,” Woodward recalls.

Instead of another round of layoffs, Bezos hired 100 new employees during his first year and approved investment in new projects. “I almost felt like clapping,” Prakash says, recalling his reaction when Bezos approved his pitch to build software to publish digital video.

More encouraging for the newsroom, Bezos’s interest seems to have expanded beyond the business model to journalism with a capital J. “He thinks journalism is an important asset for democracy,” says Walter Isaacson, who recently spoke with Bezos about the paper. And last year, he was welcomed at the Gridiron Club and Alfalfa Club dinners, annual Washington social rituals where journalists rub shoulders with politicians. When Post foreign correspondent Jason Rezaian was released from an Iranian jail earlier this year, Bezos flew him to Florida on his private jet stocked with beers and burritos after asking Rezaian’s friends what his favorite foods were. Bezos seems to have gone from being seen as a threat to Establishment intellectualism — a destroyer of bookstores and publishing houses — to being seen as, perhaps, one of its champions.

Indeed, for all the talk of innovation at the Post, the paper is succeeding in large part because of a very old-media tradition: the support of a wealthy owner. Not to mention the guidance of an increasingly legendary editor. Around the newsroom, Post reporters and editors talk about Baron as a towering and beloved figure, much like they once talked about Ben Bradlee. “When you go to the executive editor’s office and sit down, he’s personally read every sentence and is telling you what he thinks,” says Carol Leonnig, who won a 2015 Pulitzer for covering scandals in the Secret Service. Reporters also describe their boss in ways that largely comport with Liev Schreiber’s Spotlight portrayal. Baron can be affectless and relentless. One journalist recalls receiving an email from Baron that ended: “In short, I can see nothing good about this idea.” “To some degree, I have to trust how other people see me,” Baron says when I ask about Spotlight. “I would say it’s incomplete in terms of who I am. A small minority of people say I have a sense of humor.”

Baron and Bezos have a good relationship, but they rarely speak outside of the leadership team’s biweekly conference calls and corporate gatherings. “I’m not aspiring to be a buddy and he’s probably not aspiring to be my buddy,” Baron says. If Bezos ever did meddle, Baron says he’d quit: “I’m just not interested in that.”

Bezos is also proving his worth as owner in another crucial way: He doesn’t mind the heat that comes with newspaper publishing. Donald Trump has singled out Bezos and the Post in recent weeks to preemptively attack a Trump biography the Post is publishing in August. “Every hour we’re getting calls from reporters from the Washington Post asking ridiculous questions, and I will tell you, this is owned as a toy by Jeff Bezos, who controls Amazon,” Trump told Fox News in May. “He’s using the Washington Post for power so that the politicians in Washington don’t tax Amazon like they should be taxed.” Bezos responded by calling Trump’s attacks “not appropriate” onstage at a Post-sponsored event, sounding like a heroic defender of journalistic values. “Most of the world’s population live in countries where if you criticize the leader, you can go to jail,” he said. “We live in the oldest and greatest democracy in the world, with the strongest free-speech protections in the world. And it’s something, I think, we are rightly proud of. It’s critical that we be able to critically examine our leaders.” A few weeks later, Trump cut off access to Post reporters because of a headline he didn’t like.

“It’s almost as if Jeff Bezos has been in the Graham family,” Woodward tells me. “It’s the precise series of values.”

That Bezos would be interested in disrupting the newspaper industry isn’t all that surprising. After all, he founded Amazon by taking on another legacy industry. When he left Wall Street to launch his online retailer in 1994, Bezos’s big idea was that the internet could offer consumers infinitely more choice at a lower cost than brick-and-mortar bookstores. But what’s interesting is that he never tried to reinvent retail with Amazon; instead, he focused relentlessly on using technology to increase efficiency. In a way, he’s taking a similar approach at the Post.

The first new Post product Bezos put his stamp on was the paper’s tablet app. Before engineers started work on the project in the summer of 2014, Bezos told them the story of how he created the Kindle. “He said it wasn’t trying to replace the book. It was keeping the elements of the book that people like, but in an easier format,” recalls Prakash. Most newspaper apps, in Bezos’s view, deluged readers with too much content, which resulted in what he called “cognitive overhead” and a terrible reading experience. Bezos suggested experimenting with layouts that would allow readers to hover over articles, as if from a drone (this was a few months before he unveiled the Amazon Prime Air drone concept). “It completely didn’t work,” Joey Marburger says. But it pushed them away from thinking about trying to simply replicate the newspaper experience onscreen. The app launched in November 2014 with a design that displays articles in tiles with large photographs and headlines, like a series of magazine covers.

It is notoriously difficult to get people to download a new app, and most news is consumed on mobile devices rather than tablets these days. But the Post had an advantage over other newspapers when it came to tablets. Just before the app launched, the Post struck a deal to pre-install it on all Amazon Fire tablets, and Amazon now offers free six-month subscriptions to Prime members. According to sources, the app now has 100,000 paid subscribers and has been the Post’s biggest digital success story by far.

The project also proved to Post staffers that the paper could afford to take risks. “We have to ‘fail successfully,’ if that’s a proper term,” says Fred Ryan, espousing the gospel of Silicon Valley. Last year, for instance, engineers built a Mario Bros.–style video game for cell phones called Floppy Candidate, which involves players steering their presidential candidate around obstacles while collecting gold coins. “It was such an out-there, weird idea,” says Marburger, who was part of the design team. “But Jeff loved it. He played with it a ton and laughed.” Another idea was an in-house social network called the Washington Post Talent Network, which was created by former Post deputy national editor Anne Kornblut. The LinkedIn-style website allows writers to pitch stories and editors to find vetted writers to cover breaking news around the country. Bezos considers it one of the Post’s big successes and recently approved more hires to work on it.

Data is now at the heart of virtually every strategy discussion. Last year, the Post built an analytics system, Loxodo, that can track virtually all the ways readers engage with Post content. It tests which headlines and photos are encouraging the most readership, a feature common to widely used industry software like Chartbeat. But Loxodo’s algorithm automatically publishes the winner of each test so editors don’t have to continually monitor it. Another project analyzes reader behavior in the days leading up to when they subscribed, so that, instead of putting up a universal paywall of a certain number of free articles per month, the Post can better target potential subscribers. For instance, if a reader clicks on mostly articles on health, then he would be asked to subscribe after reading a fifth health article, when he’s most likely to want to keep reading.

Recently, the Post unveiled software that allows readers to bookmark articles and continue reading across multiple devices. It also gives the Post a fuller view of how readers are engaging with content. That 7,000-word investigation of a sexual assault in the Marines had an average reader engagement of 21 minutes. “This is an insanely high number. Higher than any other story we’ve done in the past year,” says Kat Downs, the graphics director.

It’s not just technology helping to sell the editorial brand; the editorial brand is being used to sell technology. Last year, the Post began licensing its custom publishing platform to publishers and universities. So far, only about a dozen publishers have signed on, including the Toronto Globe and Mail, Alaska Dispatch News, Willamette Week, and Santa Fe Reporter, but the Post believes it can eventually generate $100 million a year from the business. This spring, it launched software that solves certain problems for digital advertisers: One rapidly reduces load times for mobile display ads; another reformats video ads for vertical cell-phone screens. The goal, again, is to sell to other media companies. “I want the New York Times to call me and say, ‘Holy shit, I want that,’ ” says Jarrod Dicker, the Post’s head of ad product and technology.

Despite all these experiments, the Post has yet to find a breakout business model. “I don’t think anyone knows that answer,” Prakash acknowledges. “Our aspirations are to grow scale and try, even if we get less revenue per person, to grow the person pool so much so ultimately it’s way larger.” But even with all this experimentation, the Post is swimming upstream: The rapid spread of ad-blockers, which one study predicts will be adopted by a quarter of all internet users this year, could devastate digital revenue. Marburger tells me: “Some of these things we have no idea how to monetize. That’s a truthful answer.”

Some Post journalists worry that the Amazonian values of growing an audience by giving the customers what they want could conflict with journalism’s civic mission to report on unpleasant truths. “There’s gallows humor: Are we selling our soul for traffic?” says one longtime Post staffer. Veteran Post journalists have been spared traffic quotas, but junior employees who blog for the website feel the pressure to produce with great frequency. Baron disputes the criticism that the Post has employed so-called clickbait to juice readership. “The way I would define it is, it has a headline that tries to trick you to read the story and when you get to the story there’s nothing of any substance. I don’t think we have any of that,” he says. “I know what’s generated the traffic here. And it isn’t clickbait.” Clickbait or not, it’s clear that the Post is playing a volume game, publishing a vastly higher number of stories than its competitors. According to a recent analysis, the Post, which has a newsroom of about 700, generates 500 stories per day, compared to 230 at the Times, whose newsroom has about 1,300 employees. That’s also about twice what BuzzFeed publishes daily.

At Amazon, Bezos built a retail empire — and a $62 billion personal fortune — by investing for the long term. And he has publicly said he is committed to funding the Post until it is a sustainable business. “My sense, after a number of discussions with him, is that this is a 10-to-15-year investment,” Woodward says. Bezos is also committed to keeping the print edition going for a long while. But inside the paper, there are concerns that the cash spigot won’t run freely forever. “We are his second or third or fourth hobby,” one Post staffer says.

According to sources, the Post’s digital revenue is around $60 million, far below what the newsroom needs to function. The last time total operating revenue for the paper was published, in 2012, it was $580 million; one former executive estimates today it’s probably closer to $350 million. Another Post veteran told me that Bezos said in a meeting that the company’s annual budget, currently around $500 million, will have to be cut by 50 percent over the next three years. The newspaper denies this, and so does Prakash, who does, however, confirm that Bezos told him, “We can’t be an organization that loses gobs and gobs of money.”

The stakes for the Post’s success are high. It’s a newspaper that has all the elements in place: a tech-billionaire investor-owner, a brilliant editor, a rich history, and the resources and culture to encourage innovation. In other words, if the Post can’t invent a business model for newspapers, who can?

*This article appears in the June 27, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.