On the morning after, traumatized liberals set out hunting for answers as if Election Day were 9/11 all over again. The ubiquitous question of 15 years earlier — “Why do they hate us?” — was repurposed for Donald Trump’s demolition of the political order. Why did white working-class voters reject Hillary Clinton and the Democrats? Why did they fall for a billionaire con man? Why do they hate us?

There were, of course, many other culprits in the election’s outcome. Comey, the Kremlin, the cable-news networks that beamed Trump 24/7, Jill Stein, a Clinton campaign that (among other blunders) ignored frantic on-the-ground pleas for help in Wisconsin and Michigan, and the candidate herself have all come in for deserved public flogging. But the attitude among some liberals toward the actual voters who pulled the trigger on Election Day has been more indulgent, equivocal, and forgiving. Perhaps those white voters without a college degree who preferred Trump by 39 percentage points — the most lopsided margin in the sector pollsters define as “white working class” since the 1980 Ronald Reagan landslide — are not “deplorables” who “cling to guns and religion” after all. Perhaps, as Joe Biden enthused, “these are good people, man!” who “aren’t racist” and “aren’t sexist.” Perhaps, as Mark Lilla argued in an influential essay in the New York Times, they were turned off mostly by the Democrats’ identity politics and rightfully felt excluded from Clinton’s stump strategy of name-checking every ethnicity, race, and gender in the party’s coalition except garden-variety whites. Perhaps they should hate us.

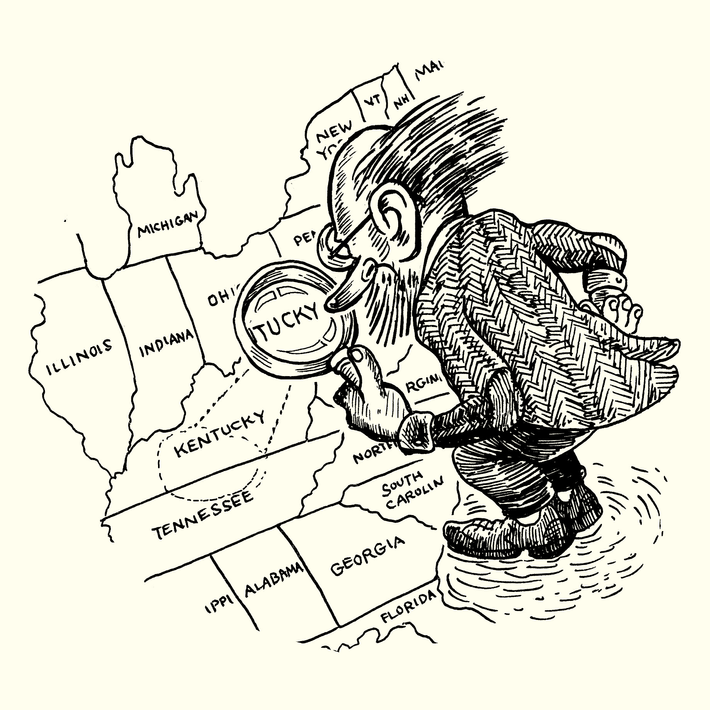

While many, if not most, of those in #TheResistance of the Democratic base remain furious at these voters, the party’s political class and the liberal media Establishment are making a concerted effort to convert that rage into empathy. “Democrats Hold Lessons on How to Talk to Real People” was the headline of a Politico account of the postelection retreat of the party’s senators, who had convened in the pointedly un-Brooklyn redoubt of Shepherdstown, West Virginia. Democrats must heed the rural white enclaves, repeatedly instructs the former Pennsylvania governor and MSNBC regular Ed Rendell. Nicholas Kristof has pleaded with his readers to understand that “Trump voters are not the enemy,” a theme shared by the anti-Trump conservative David Brooks. “We’re Driving to the Inauguration With a Trump Supporter” was the “Kumbaya”-tinged teaser on the Times’ mobile app for a roundup of on-the-ground chronicles of these exotic folk invading Washington. Even before Trump’s victory, commentators were poring through fortuitously timed books like Nancy Isenberg’s sociocultural history White Trash and J. D. Vance’s memoir, Hillbilly Elegy, seeking to comprehend and perhaps find common ground with the Trumpentariat. As measured by book sales and his appeal to much the same NPR-ish audience, Vance has become his people’s explainer-in-chief, the Ta-Nehisi Coates, if you will, of White Lives Matter.

The outbreak of Hillbilly Chic among liberals is an inverted bookend to Radical Chic, the indelible rubric attached by Tom Wolfe in 1970 (in this magazine) to white elites in Manhattan then fawning over black militants. In both cases, the spectacle of liberals doting on a hostile Other can come off like self-righteous slumming. But for those of us who want to bring down the curtain on the Trump era as quickly as possible, this pandering to his voters raises a more immediate and practical concern: Is it a worthwhile political tactic that will actually help reverse Republican rule? Or is it another counterproductive detour into liberal guilt, self-flagellation, and political correctness of the sort that helped blind Democrats to the gravity of the Trump threat in the first place? While the right is expert at channeling darker emotions like anger into ruthless political action, the Democrats’ default inclination is still to feel everyone’s pain, hang their hats on hope, and enter the fray in a softened state of unilateral disarmament. “Stronger Together,” the Clinton-campaign slogan, sounded more like an invitation to join a food co-op than a call to arms. After the debacle of 2016, might the time have at last come for Democrats to weaponize their anger instead of swallowing it? Instead of studying how to talk to “real people,” might they start talking like real people? No more reading from wimpy scripts concocted by consultants and focus groups. (Clinton couldn’t even bring herself to name a favorite ice-cream flavor at one campaign stop.) Say in public what you say in private, even at the risk of pissing people off, including those in your own party. Better late than never to learn the lessons of Trump’s triumphant primary campaign that the Clinton campaign foolishly ignored.

This is a separate matter from the substantive question of whether the party is overdue in addressing the needs of the 21st-century middle class, or what remains of it. The answer to that is yes, as a matter of morality, policy, and politics. Americans below the top of the heap, with or without college degrees and regardless of race, have been ill served by the axis of Robert Rubin, Lawrence Summers, and the Davos-class donor base that during Bill Clinton’s presidency helped grease the skids for the 2008 economic collapse and allowed the culprits to escape from the wreckage unscathed during Barack Obama’s. That Hillary Clinton pocketed $21.6 million by speaking to banks and other corporate groups after leaving the State Department is just one hideous illustration of how the Democrats opened the door for Trump to posture as an anti-Establishment champion of “the forgotten men and women.” In the bargain, she gave unenthused Democrats a reason to turn to a third-party candidate or stay home.

But it’s one thing for the Democratic Party to drain its own swamp of special interests and another for it to waste time and energy chasing unreachable voters in the base of Trump’s electorate. For all her failings, Clinton received 3 million more votes than Trump and lost the Electoral College by the mere 77,744 votes that cost her the previously blue states of Michigan (which she lost by .2 of a percentage point), Wisconsin (.8 point), and Pennsylvania (.7 point). Of the 208 counties in America that voted for Obama twice and tipped to Trump in 2016, more than three-quarters were in states Clinton won anyway (some by a landslide, like New York) or states that have long been solidly red.

The centrist think tank Third Way is focusing on the Rust Belt in a $20 million campaign that its president, a former Clinton White House aide, says will address the question of how “you restore Democrats as a national party that can win everywhere.” Here is one answer that costs nothing: You can’t, and you don’t. The party is a wreck. Post-Obama-Clinton, its most admired national leaders (Biden, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren) are of Social Security age. It rules no branch of federal government, holds only 16 governorships, and controls only 14 state legislatures. The Democrats must set priorities. In a presidential election, a revamped economic program and a new generation of un-Clinton leaders may well win back the genuine swing voters who voted for Trump, whether Democratic defectors in the Rust Belt or upscale suburbanites who just couldn’t abide Hillary. But that’s a small minority of Trump’s electorate. Otherwise, the Trump vote is overwhelmingly synonymous with the Republican Party as a whole.

That makes it all the more a fool’s errand for Democrats to fudge or abandon their own values to cater to the white-identity politics of the hard-core, often self-sabotaging Trump voters who helped drive the country into a ditch on Election Day. They will stick with him even though the numbers say that they will take a bigger financial hit than Clinton voters under the Republican health-care plan. As Trump himself has said, in a rare instance of accuracy, they won’t waver even if he stands in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoots somebody. While you can’t blame our new president for loving “the poorly educated” who gave him that blank check, the rest of us are entitled to abstain. If we are free to loathe Trump, we are free to loathe his most loyal voters, who have put the rest of us at risk.

Liberals now looking to commune with the Trump base should check out the conscientious effort to do exactly that by the Berkeley sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild. As we learn in her election-year best seller, Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right, she poured her compassion, her anthropological sensibility, and five years of her life into “a journey to the heart of the American right.” Determined to burst out of her own “political bubble,” Hochschild uprooted herself to the red enclave of Lake Charles, Louisiana, where, as she reports, there are no color-coded recycling bins or gluten-free restaurant entrées. There she befriended and chronicled tea-party members who would all end up voting for Trump. Hochschild liked the people she met, who in turn reciprocated with a “teasing, good-hearted acceptance of a stranger from Berkeley.” And lest liberal readers fear that she was making nice with bigots in the thrall of their notorious neighbor David Duke, she offers reassurances that her tea-partyers “were generally silent about blacks.” (Around her, anyway.)

Hochschild’s mission was inspired by Thomas Frank’s What’s the Matter With Kansas? She wanted “to scale the empathy wall” and “unlock the door to the Great Paradox” of why working-class voters cast ballots for politicians actively opposed to their interests. Louisiana is America’s ground zero for industrial pollution and toxic waste; the stretch of oil and petrochemical plants along the Mississippi between New Orleans and Baton Rouge is not known as “cancer alley” for nothing. Nonetheless, the kindly natives befriended by Hochschild not only turned out for Trump but have consistently voted for local politicians like Steve Scalise (No. 3 in Paul Ryan’s current House leadership), former senator David Vitter, and former governor Bobby Jindal, who rewarded poison-spewing corporations with tax breaks and deregulation even as Louisiana’s starved public institutions struggled to elevate the health and education of a populace that ranks near the bottom in both among the 50 states. Hochschild’s newfound friends, some of them in dire health, have no explanation for this paradox, only lame, don’t–wanna–rock–Big Oil’s–tanker excuses. Similarly unpersuasive is their rationale for hating the federal government, given that it foots the bill for 44 percent of their state’s budget. Everyone who takes these handouts is a freeloader except them, it seems; the government should stop favoring those other moochers (none dare call them black) who, in their view, “cut the line.” Never mind that these white voters who complain about “line cutters” are themselves guilty of cutting the most important line of all — the polling-place line — since they are not subjected to the voter-suppression efforts being inflicted on minorities by GOP state legislatures, the Roberts Supreme Court, and now the Jeff Sessions–led Department of Justice.

In “What So Many People Don’t Get About the U.S. Working Class,” a postelection postmortem published to much op-ed attention by the Harvard Business Review (and soon to be published in expanded form as what will undoubtedly be another best-selling book), the University of California law professor Joan C. Williams proposes that other liberals do in essence what Hochschild did. “The best advice I’ve seen so far for Democrats is the recommendation that hipsters move to Iowa,” Williams writes — or to any other location in the American plains where “shockingly high numbers of working-class men are unemployed or on disability, fueling a wave of despair deaths in the form of the opioid epidemic.” She further urges liberals to discard “the dorky arrogance and smugness of the professional elite” (epitomized in her view by Hillary Clinton) that leads them to condescend to disaffected working-class whites and “write off blue-collar resentment as racism.”

Hochschild anticipated that Williams directive, too. She’s never smug. But for all her fond acceptance of her new Louisiana pals, and for all her generosity in portraying them as virtually untainted by racism, it’s not clear what such noble efforts yielded beyond a book, many happy memories of cultural tourism, and confirmation that nothing will change anytime soon. Her Louisianans will keep voting for candidates who will sabotage their health and their children’s education; they will not be deterred by an empathic Berkeley visitor, let alone Democratic politicians.

Had Hochschild conducted her Louisiana experiment, as Williams suggests, in Iowa or the Rust Belt towns hollowed out by factory closings and the opioid epidemic, the results would have been no more fruitful. You need not take a liberal’s word for this. The toughest critics of white blue-collar Trump voters are conservatives. Witness Kevin D. Williamson, who skewered “the white working class’s descent into dysfunction” in National Review as Trump was piling up his victories in the GOP primaries last March. Raised in working-class West Texas, Williamson had no interest in emulating the efforts of coastal liberals to scale empathy walls. Instead, he condemns Trump voters for being “in thrall to a vicious, selfish culture whose main products are misery and used heroin needles.” He chastises them for embracing victimhood by blaming their plight on “outside forces” like globalization, the Establishment, China, Washington, immigrants — and “the Man” who “closed the factories down.” He concludes: “Donald Trump’s speeches make them feel good. So does OxyContin.”

Though some in Williamson’s ideological camp recoiled from his blunt language, he’s no outlier among conservatives. The popular blogger Erick Erickson tweeted last year that “a lot of Trump voters have failed at life and blame others for their own poor decisions.” His and Williamson’s line of attack echoes the conservative sociologist Charles Murray, most recently famous for being shouted down at Middlebury College in Vermont, where some remembered his co-authorship of The Bell Curve, a Clinton-era slab of spurious science positing that racial genetics play a role in limiting blacks’ performance on I.Q. tests. In a 2012 Obama-era sequel titled Coming Apart: The State of White America 1960–2010, Murray switched his focus to whites and reprimanded those in the lower strata for abandoning family values and civic virtues. (This time, the culprit was not the genetic code but the anything-goes social mores wrought by leftist 1960s counterculture.)

The much-beloved Hillbilly Elegy is a kinder, gentler version of the same condemnatory conservative take on the white working class, stitched into the candid and touching life story of the author, now 32, successful, and a Republican who, like Williamson and Murray, is no Trump fan. Against all odds, Vance triumphed over a sometimes brutal and always hand-to-mouth working-class upbringing in Middletown, Ohio, where his hillbilly family had migrated from coal country in eastern Kentucky. His mother was a junkie who married five times, and during one two-year interval the young Vance lived in four different homes. The powerful scenes between the addled mother and her bruised child are reminiscent of the mother-son interactions in the Oscar-winning movie Moonlight, albeit with a white heterosexual protagonist.

Vance has limited sympathy for his mother or the other drug addicts and “welfare queens,” all white, of his hometown. He describes in detail how they game entitlements like food stamps to support their addictions, whether to opioids or flashy consumer goods. Echoing Williamson, he accuses them of responding to the collapse of the old industrial economy “in the worst way possible,” by acting “like a persecuted minority” and blaming everyone but themselves for their plight: “We talk about the value of hard work but tell ourselves the reason we’re not working is some perceived unfairness: Obama shut down the coal mines, or all the jobs went to the Chinese.” Like Hochschild and Joan Williams, Vance nonetheless goes out of his way to clear working-class whites from the charge of racism. What infuriates them about Obama, he writes, is not the color of his skin but that he is “brilliant, wealthy, and speaks like a constitutional law professor.” (That Obama, like Vance, was rescued from his problematic parental dynamic in part by his white Middle American grandparents goes unmentioned.) But that’s one of the few spirited defenses he mounts of those whom forgiving liberals like Hochschild, Kristof, and the rest want to usher into the Democratic fold. In nearly every other way, he, like Williamson, finds them to be a basket of deplorables even without leveling the charge of bigotry.

At least Hillary Clinton and her party aspired to do something, however inchoate, for the white working class. Vance, Williamson, and Murray — every bit as anti-government as the dysfunctional whites they deplore — have little use for a federal safety net. They instead offer Trump voters lectures about the virtues of self-help. In Hillbilly Elegy, Vance concludes by demanding that “we hillbillies … wake the hell up.” It’s a retread of the magical thinking Murray offered four years earlier (to no avail) in Coming Apart, in which he suggested that a “Great Civic Awakening” among the out-of-touch upper classes would somehow lift up the dysfunctional whites below. For his part, Williamson suggests that Trump-and-OxyContin- addicted working-class whites rent U-Hauls and flee their dying towns for an unspecified future, with no prospect of any government program to rescue them as FDR’s Resettlement Administration once aided Okies who packed up all they had in beat-up jalopies to flee the Dust Bowl.

Vance, you’d think, would be more generous than this. As an alumnus of Yale Law School who ended up working as a Silicon Valley investor under the aegis of Peter Thiel, he is too successful and sophisticated to leave unacknowledged the government help he received along the way. By his own account, his grandmother’s “old-age benefits” kept him from going hungry as a child. He cites Pell grants, low-interest government loans, bargain in-state tuition at Ohio State, and the GI Bill (he enlisted in the Marine Corps after college) for their role in making his elite education and worldly achievements possible. Vance recently announced that he is moving back to Ohio to start a nonprofit organization to help combat the opioid epidemic. But in Hillbilly Elegy, he minimizes the usefulness of government programs and social services, which “often make a bad problem worse.” He approvingly quotes a friend who worked in the White House (presumably a Republican White House) as saying “You probably can’t fix these things” and that the best you can do is “put your thumb on the scale a little for the people at the margins.” In White Trash, Nancy Isenberg might as well be talking about Vance when she writes (of Nixon-era conservatives) that the “same self-made man who looked down on white trash” conveniently chose “to forget that his own parents escaped the tar-paper shack only with the help of the federal government” as he now pulled up “the social ladder behind him.”

The conservative contempt for Trump voters — omnipresent among the party’s Establishment until the Election Day results persuaded all but the most adamant NeverTrumpers to fall into line — would seem to give the Democrats a big opening to win them over. Bemoaning how his blue native state of West Virginia turned red well before Trump beat Clinton by 42 percentage points, the veteran liberal editor and author Charles Peters was hopeful the tide could be reversed with time and, yes, empathy: “If we don’t listen, how can we persuade?” he implored readers of the Times. Those who want to start that listening now can download an “Escape Your Bubble” browser extension to sweep opposing views into their Facebook feeds; both MSNBC and CNN have stepped up their efforts to expose their audiences to Trumpist voices. But getting out of one’s bubble can’t be a one-way proposition. It won’t make any difference if MSNBC viewers hear from the right while Fox News viewers remain locked in their echo chamber. Nor will it matter if hipsters — or Democratic politicians — migrate from the Bay Area and Brooklyn to Louisiana and Iowa to listen to white working-class voters if those voters don’t listen back. There’s zero evidence that they will. The dug-in Trump base shows no signs of varying its exclusive diet of right-wing media telling it that anyone who contradicts Trump, Rush, or Breitbart is peddling “fake news.” When Bernie Sanders visits West Virginia to tell his faithful that they are being raped and pillaged by Trump-administration policies that will make the Trump University scam look like amateur hour, he is being covered by MSNBC, not Fox News, whose passing interest in Sanders during primary season was attributable to his attacks on Clinton.

The most insistent message of right-wing media hasn’t changed since the Barry Goldwater era: Government is inherently worthless, if not evil, and those who preach government activism, i.e., liberals and Democrats, are subverting America. Facts on the ground, as Hochschild saw in Louisiana, do nothing to counter this bias. In his definitive recent book on the Rust Belt drug plague, Dreamland, the journalist Sam Quinones observes that “other than addicts and traffickers,” most of the people he encountered in his reporting were government workers. “They were the only ones I saw fighting this scourge,” he writes. “We’ve seen a demonization of government and the exaltation of the free market in America over the previous 30 years. But here was a story where the battle against the free market’s worst effects was taken on mostly by anonymous public employees.” In that category he includes local police, prosecutors, federal agents, coroners, nurses, Centers for Disease Control scientists, judges, state pharmacists, and epidemiologists. Yet even now, Reagan’s old dictum remains gospel on the right (Vance included): “The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the government and I’m here to help.” In Portsmouth, Ohio, the epicenter of opiate-pill mills and of Quinones’s book, Trump won by a landslide. As he did in Ohio’s Butler County, where Vance grew up and which now ranks eighth among all American counties in the increase in the rate of drug-related deaths between 2004 (when opioid fatalities first spiked) and 2014.

As polls uniformly indicate, nothing that has happened since November 8 has shaken that support. And what are Trump’s voters getting in exchange for their loyalty? For starters, there’s Ryan-Trumpcare, which, on top of its other indignities, eliminates the requirement that Medicaid offer addiction treatment, which over the past two years has increased exponentially in opioid-decimated communities where it is desperately needed. Meanwhile, Trump’s White House circle of billionaires is busily catering to its own constituency, prioritizing tax cuts for the fabulously wealthy while pushing to eliminate rural-development agencies that aid Trump voters.

The go-to explanation for the steadfastness of Trump’s base was formulated by the conservative pundit Salena Zito during the campaign: The press takes Trump “literally but not seriously” while “his supporters take him seriously but not literally.” If this is true, then presumably his base will remain onboard when he fails to deliver literally on his most alluring promises: “insurance for everybody” providing “great health care for a fraction of the price”; the revival of coal mining; a trillion-dollar infrastructure mobilization producing “millions of new jobs” and accompanied by “massive tax relief” for all; and the wall that will shield America from both illegal immigration and the lethal Mexican heroin that has joined OxyContin as the working-class drugs of choice.

There’s no way liberals can counter these voters’ blind faith in a huckster who’s sold them this snake oil. The notion that they can be won over by some sort of new New Deal — “domestic programs that would benefit everyone (like national health insurance),” as Mark Lilla puts it — is wishful thinking. These voters are so adamantly opposed to government programs that in some cases they refuse to accept the fact that aid they already receive comes from Washington — witness the “Keep Government Out of My Medicare!” placards at the early tea-party protests.

Perhaps it’s a smarter idea to just let the GOP own these intractable voters. Liberals looking for a way to empathize with conservatives should endorse the core conservative belief in the importance of personal responsibility. Let Trump’s white working-class base take responsibility for its own votes — or in some cases failure to vote — and live with the election’s consequences. If, as polls tell us, many voters who vilify Obamacare haven’t yet figured out that it’s another name for the Affordable Care Act that’s benefiting them — or if they do know and still want the Trump alternative — then let them reap the consequences for voting against their own interests. That they will sabotage other needy Americans along with them is unavoidable in any case now — at least until voters stage an intervention in an election to come.

Trump voters should also be reminded that the elite of the party they’ve put in power is as dismissive of them as Democratic elites can be condescending. “Forget your cheap theatrical Bruce Springsteen crap,” Kevin Williamson wrote of the white working class in National Review. “The truth about these dysfunctional, downscale communities is that they deserve to die. Economically, they are negative assets. Morally, they are indefensible.” He was only saying in public what other Republicans like Mitt Romney say about the “47 percent” in private when they think only well-heeled donors are listening. Besides, if National Review says that their towns deserve to die, who are Democrats to stand in the way of Trump voters who used their ballots to commit assisted suicide?

So hold the empathy and hold on to the anger. If Trump delivers on his promises to the “poorly educated” despite all indications to the contrary, then good for them. Once again, all the Trump naysayers will be proved wrong. But if his administration crashes into an iceberg, leaving his base trapped in America’s steerage with no lifeboats, those who survive may at last be ready to burst out of their own bubble and listen to an alternative. Or not: Maybe, like Hochschild’s new friends in Louisiana’s oil country, they’ll keep voting against their own interests until the industrial poisons left unregulated by their favored politicians finish them off altogether. Either way, the best course for Democrats may be to respect their right to choose.

*This article appears in the March 20, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.

*A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that Joe Wilson shouted during the president’s State of the Union address.