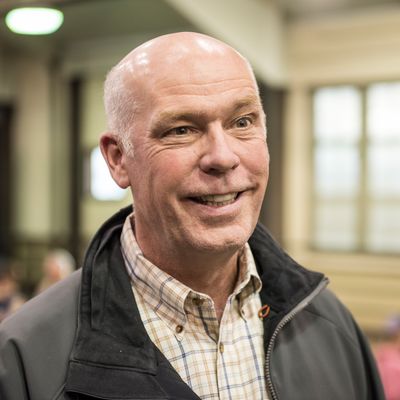

Hours after Montana congressional candidate Greg Gianforte was accused of “body slamming” Guardian reporter Ben Jacobs on the eve of a special election for the state’s U.S. House seat, moveon.org began running an ad intended to make sure every voter heard the audio of the incident. At the end, this line flashed on the screen: “Greg Gianforte. Unfit to serve.”

Three local papers came to the same conclusion, rescinding their endorsements of the Republican candidate. But technically, that’s incorrect. Gianforte won the election on Thursday night, and there’s no reason that he can’t be sworn in as the next congressman from Montana, though he’s been charged with misdemeanor assault.

The Constitution says members of the House and Senate must meet three requirements:

• All members of the House must be at least 25 years old, and members of the Senate must be at least 30 years old.

• Members of the House must have been a U.S. citizen for at least seven years, and members of the Senate must have been a U.S. citizen for at least nine years.

• They have to be an “inhabitant” of the state “when elected.”

The Constitution also says that the House “shall be the Judge of the Elections, Returns and Qualifications of its own Members.” That suggests the House has vast control over who gets to be a member of Congress, but as the Washington Post notes, the Supreme Court shot down that idea in 1969. Three years earlier, when Representative Adam Clayton Powell was reelected despite an ethics scandal, members of the House voted to exclude him from the 90th Congress. He challenged the move and the Supreme Court ruled in Powell v. McCormack that the House can determine if members meet the three requirements listed above, but they can’t create new qualifications — like, for instance, not facing assault charges.

So while House Speaker Paul Ryan’s comment on Gianforte’s alleged body slam was a dodge, it was also technically correct. “If he wins, he has been chosen by the people of Montana, who their congressman’s going to be,” he said. “I’m going to let the people of Montana decide who they want as their representative.”

A sitting member of Congress can be removed by a two-thirds vote in the House, but that method has only been successfully used five times, and three occurred in the wake of the Civil War. It’s highly unlikely that a misdemeanor assault charge would spur Congress to take action against Gianforte, as it’s fairly common for members to serve while facing charges. By the Post’s count, more than two dozen members of Congress were indicted between 1980 and 2015.

Even if Gianforte receives the maximum penalty for misdemeanor assault in Montana, six months in jail, he could still continue serving in Congress. As factcheck.org explains, the Constitution does not say people convicted of crimes are barred from serving, and one member of Congress was actually elected from prison:

In 1798, Rep. Matthew Lyon ran for Congress from prison and won. He assumed his seat in Congress after serving four months in prison for “libeling” President John Adams. An effort was made to expel Lyon from the House, but it failed.

Since some Republicans in Congress responded to the Gianforte assault story by cracking jokes about attacking journalists, there’s obviously little political will to take drastic measures against him. But Vox notes that when convicted, other members of Congress have been privately pressured to resign.

At the very least, Gianforte’s political future is now a little less bright.

“If [Gianforte] is elected, they’re going to want to hide him. So [the assault] probably harms the chances of him getting a really good committee assignment,” Michele Swers, a congressional expert at American University, told Vox. “He almost certainly won’t get as prominent a committee assignment as he would have otherwise.”

Down the line, that could prevent him from achieving his real goal, which, according to Matt McKenna, a longtime Montana politics insider and adviser to Gianforte’s opponent Rob Quist, is another crack at the governorship.

“This is the first day of the end of Greg Gianforte’s political career,” McKenna told the Post, following his win. “It may seem like he got away with this because so many people already voted, but they will deny him the prize he really wants which is the governor’s office. He could go to jail. He still has to be arraigned.”