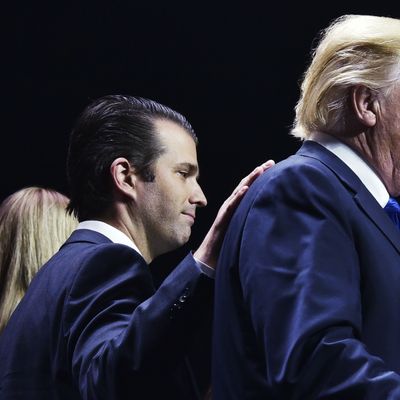

On Tuesday, Donald Trump Jr. released a set of emails between himself and music publicist Rob Goldstone proving he knew the Russian government was working to help elect his father. It was the climax in a series of reports from the New York Times about a meeting in June of last year between Trump Jr. and a Kremlin-affiliated attorney, organized to discuss the transfer of damaging information about Hillary Clinton to the Trump camp.

The fallout from these revelations — as close to a smoking gun as we’ve gotten so far in the Trump-Russia scandal — is still unknown. But the public appearance of Trump Jr.’s email chain definitely raises a lot of questions. Legally, did he do anything wrong? Is there any historical precedent for his actions? And what does this mean for Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation?

To answer these queries and more, Daily Intelligencer spoke with election law expert Robert Bauer, who served as White House counsel to former President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2011.

Campaigns seek out damaging information about their opponents all the time. What makes this Donald Trump Jr. situation unique?

The law specifically prohibits soliciting or accepting anything of value from a foreign national. When we talk about information, which is a very general term – we could be talking about research reports, polling data, a cache of emails — they have value. The election laws pick up, for this particular prohibition, and in other provisions as well, contributions that consist of something in kind. Something that is not acquired with cash, something that is received in the form that somebody else procured and paid for it.

The word collusion has been thrown around a lot to describe the Trump campaign’s possible relationship to Russia. Legally, what does that mean?

Collusion, I think, is a shorthand. It means some sort of conspiracy, conniving, collaboration. In election law there’s a term called coordination and that essentially captures circumstances in which a campaign has found somebody to spend money on its behalf. The campaign is a beneficiary of an arrangement by which somebody might, for example, advertise on behalf of the campaign, or purchase goods and services to be delivered to the campaign. If a candidate is a party to that understanding, then in effect it’s really no different than the campaign getting money directly from the donor. It’s benefiting with its understanding, its consent, and its request. It’s benefiting from the expenditure of the fund. And so it’s treated as a contribution like any other because the spending was coordinated. And that’s where the term coordination comes from.

Do you think coordination is potentially an appropriate term for what we’re seeing with the Trump Jr. meeting?

It seems so. I’m not suggesting that all the evidence is in or where it’s ultimately going to lead, but we have email evidence today that somebody with ties to the Russian government, and known by Donald Trump Jr. to have ties to the Russian government, advised that the Russian government was looking to help his father, told him that somebody close to the Russian government — described in an email as a Russian government lawyer — was coming to a meeting to provide some benefit to the campaign. So I don’t see how that isn’t coordinated activity. There’s a party who wants to be helpful to the campaign — in this case, a foreign government — and the campaign ascends to the help and sort of collaborates around, or communicates around, what that help might be.

There are two categories of laws that may apply not just to Trump Jr., but to the Trump campaign and Russia’s relationship as a whole: federal election laws and criminal conspiracy laws. Is that correct?

Yeah, and the conspiracy laws connect to the election laws. Because you would have a conspiracy, presumably, should the evidence ultimately support it, to violate the campaign-finance laws. So, the conspiracy would not be free-floating and independent, it would tie directly into the violation of the campaign laws.

With conspiracy laws, the crime is the agreement itself to commit a crime. It doesn’t matter whether that effort succeeds or is ever carried out.

That’s correct.

Okay. Federal election laws say that foreign nationals or foreign governments can’t contribute a “thing of value” to a presidential campaign. What does that actually mean?

“Thing of value,” anything of value, also applies to contributions across the board, not just contributions from foreign nationals. And the theory behind it is fairly straightforward, which is you can, for example, pay for a hall to hold a rally in. Find the cash, pay the rental. Or the owner of the hall can just provide it to you. And if the owner of the hall provides it to you, the owner of the hall’s not providing you with cash, the owner of the hall is providing you with a venue for an event and it’s fundamentally the same thing to you. It’s the same value to you as if, in fact, you had purchased it yourself.

So, the “thing of value” limitation is designed to pick up so-called “in-kind” contributions. Not just contributions as cash. Without it, the elections laws would basically be made somewhat nonsensical. There would be no reason to have a contribution limit if the easy way around it was to simply avoid paying cash and to simply provide, in concrete form, whatever it was that the campaign wanted.

So far, there is no evidence that the Trump campaign had anything to do with the DNC hacks or John Podesta’s leaked emails from last year – but are those things we can consider “things of value” during a campaign?

The hacking of the material and then its release into the public sphere?

Yes.

I think you absolutely can confirm that as a thing of value. President Trump at one point, as a candidate, called upon the Russians to locate the so-called deleted Secretary Clinton emails and said, “I hope you find them.” Later it was said, “Well, maybe he was joking.” Well, now it turns out that the campaign was actively looking for this and believed it was very important. I would stress in particular that today the Russian lawyer, Natalia Veselnitskaya, said the campaign wanted that material, or wanted negative information on Hillary Clinton very badly.

An important part of the Trump campaign’s strategy was to create major doubts about Hillary Clinton. You recall the chants of “lock her up,” and President Trump at one point said he was going to appoint a prosecutor, he was going to do a direct prosecution of Clinton. And so any material that somebody could acquire that would dramatically support those claims was of exceptional value to the campaign. Whatever this lawyer promised might have been one thing, the stolen emails might have been another. But one way or the other, they were looking for negative product they thought would be helpful to them on a matter of central strategic significance to the campaign.

How difficult would it be to litigate a “thing of value” in court?

There’s a complicated line of cases and law that have to do with “what does it mean to coordinate with an organization that’s spending money.” Sometimes, the candidate says, “Well, I’m engaged in free speech. The organization is engaged in free speech.” There has to be some limit to how far you can regulate communication between allies. So, I go to see somebody who I think is a supporter and I tell that person something about my campaign that I’m trying to accomplish. Three months later the supporter puts advertising on the air. The supporter is going to say, “Well, that’s my free speech. I’m just taking informed speech and putting it on the air.” I don’t know that you can see that free-speech defense applying here. It seems to me – and I think there’s law on this point – the foreign-national prohibition is for a very different purpose and the free-speech interests here are significantly attenuated.

The purpose of the foreign-national prohibition is to defend the larger political community, as a court recently said. This goes to a fundamental question of defining and protecting what we consider to be the political community entitled to participate in the choice of our elected leaders, and so the breadth of the government’s interest, the scope of the government’s interest, is very broad and very strong, and for that reason some of the free-speech defenses in the coordination world, or in the cases of coordination that you oftentimes see in the domestic sphere, don’t have nearly that force. And I don’t think it ultimately would be upheld in the case where we’re talking about involving a foreign government coordinating with a campaign to win an election in the United States.

And federal election laws also prohibit U.S. nationals from providing substantial assistance to a foreign national?

That’s correct. It prohibits U.S. nationals from assisting foreign nationals in trying to influence an election.

Does that cover trying — but not necessarily succeeding — to provide substantial assistance?

I don’t know that it’s clear what constitutes substantial assistance or whether it would be a liability to merely attempt to provide substantial assistance. It’s certainly a conspiracy to violate the election laws, as you pointed out. It doesn’t have to end in a successful attempt. It can be an attempt, in and of itself, to bring about the fulfillment of a foreign national’s goals.

If you assume that the Putin regime wants to affect the outcome of the election and the Trump campaign wants to help them do it, the Trump campaign believes it would be destabilizing to the Clinton campaign. It would demoralize the Democrats. The Putin government is delighted to do it because it wants to create a bit of chaos in the course of our election. And if the Trump campaign goes about actively aiding the Russians in doing this, denying that they’re involved, refusing to condemn them, reading the WikiLeaks emails, you can read all of that as a form of providing substantial assistance to an effort that, we now know from the emails, they understood that the Russian government was undertaking.

So it seems that there are two types of criminal conspiracy laws that would apply here: to defraud the United States or to make an offense against the United States.

Yes, that’s generally correct.

And defrauding the United States has a broad meaning here, right?

That’s correct, impeding, for example, as one commentator suggested, the lawful administration of a federal election.

How might these recent revelations surrounding Trump Jr. relate to Robert Mueller’s special investigation?

Without a doubt, it raises a whole series of questions that he’s going to be looking into. These emails don’t answer all of the questions. They’re highly suggestive about intent and about specific activities, the intent of working with the Russians on this campaign to try to win the election for Donald Trump. I think it totally underscores the seriousness of this aspect of whatever else — there may be other issues — that Special Counsel Mueller is looking into.

How does being president shield Donald Trump from whatever the fallout of this is?

Understand that the Office of Legal Counsel’s opinion on this subject — and there have been two, one in 1973, and one in 2000 — those opinions are not uncontested. That is to say, this is an executive-branch judgment about the president’s immunity from prosecution while in office. I, for one, don’t share it. I don’t think it’s correct. There are other scholars who do think it’s correct. But it’s certainly not a settled issue at all. And there’s good reason to believe that if called upon to judge the question, a court might conclude, in fact, that the president can be indicted while in office. I’m not saying that would happen to this president, I’m not speaking about the current case, but I wanted to address the general proposition.

Is there any historical precedent for what we’re seeing right now? In terms of what we now know Trump Jr. did, or about Trump’s campaign and Russia in general?

Nothing like what we’re seeing right now has ever occurred — certainly in the modern era — in an American presidential or congressional election. As far as a campaign that is explicitly or actively cooperating with a foreign government in the mutual goal of winning an election, I cannot think of anything like it. Obviously in ‘96 and ’97, Republicans alleged that Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign had received significant foreign funding from Chinese government sources. The suggestion was, for example, that there were particular contributors to the campaign who were, as I recall, treated as proxies or agents for foreign-government interests. But that investigation never led to any such conclusion.

Is there anything you think the public should know about Trump Jr.’s emails, Trump’s campaign, and Russia going forward?

People tend to view this as an individual issue for Donald Trump Jr. There’s a question of his own personal liability or the liability of Mr. [Jared] Kushner and [former campaign chair Paul] Manafort. They’re agents of the campaign: They’re speaking for the campaign, they’re holding a meeting at Trump Tower. I think that one of the things to keep in mind about the exchange of emails today is that it opens up the question of campaign organization liability. That is to say, the campaign as an entity. That, of course, brings it a lot closer to President Trump.

That issue of campaign liability exposes Trump more?

Well, the one question it raises is if this is a campaign venture — and it certainly appears from the emails that it is — rather than some foolish gambit on the part of Donald Trump Jr. Is it plausible that after learning the Russian government is committed to helping Trump and believes it may have information that is damaging to Hillary Clinton, Trump’s campaign manager, much less his son, never informed Trump himself?

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.