Things you learn at an open-call public-address announcer audition in a dead-quiet basketball arena: An accent — be it Brooklyn or Jersey or vaguely Australian — can disappear into the boom of the mic. Breath is loud, louder still when there at nerves at play. Roaring “two-point goal” in an empty stadium is strangely uncomfortable. But not as uncomfortable as a low-energy announcer talking to empty seats. “Timofey Mozgov” is the minefield you’d expect. “Caris LeVert” is the one you don’t. No crowd exists to swallow the P.A.’s reverb, so mispronouncing a name is as agonizing as it seems. A guy will stumble on the word Nets, and it will break your heart.

But this, apparently, is what it takes to find the next voice of Brooklyn’s basketball team. The person to call the lineups and in-game action, and genially remind thousands of fans they can’t smoke in the Barclays Center. The position is now vacant after the Nets’ previous emcee, David Diamante, announced last month he was leaving after six years. So the organization hosted open auditions at Barclays on Tuesday afternoon to find a replacement. Just about anybody was welcome to give it a shot.

About 175 people did, almost all of them men with a voice that someone once told them made them destined to be an announcer. (“Three,” estimated the woman at the check-in desk, about the number of ladies who showed.) Staff leads them down to the holding room, an empty court-level concession stand. There, auditioners stake out spots, fill out applications, pin numbers — which for some reason, start in the 200s — on their shirts. Then, they wait.

“I was born,” bellows Perry “Trip” Patterson, a 56-year-old from Brooklyn, when asked how he prepared for the audition. He laughed, slapping hands with Kim Osborne, 54, of Manhattan, who sat across from him at a bar-top table. “Go on baby, make it happen. Yeah, I was born.”

Patterson, in black-framed glasses and hot-orange shorts, is mostly kidding. He says he’s done voice-over and radio work, but never met enough success to call it a career. “At this age, I figure 50s are today’s 40s.”

“That’s right,” Osborne chimes in.

“Don’t give up till the wheels fall off. Keep moving,” Patterson continues. “They just going to hear what I got, and say: ‘You’re the man for the job.’”

Osborne, an “actor-slash-hairstylist” with long curly hair and a white-tinged beard, also thought, why not try. “Nothing is going to happen unless I put myself out there and receive it. Make it happen.”

“Put it out in the universe,” Patterson echoes.

For all the Pattersons and Osbornes with a dollar-and-a-dream attitude, many at the tryouts have a background announcing for high school or colleges or smaller markets. They are amateurs ready to go pro. Like 29-year-old Sean Stackhouse, who leans against a wall, looking not unlike a man at risk of puking. He admits he’s a little nervous, but doesn’t sound so when he describes his ten years calling games for the Bears of the University of Maine. He found out about the auditions through Facebook, drove down to Brooklyn. “I thought, you know what, I’m not doing anything today. This would be really cool,” he says. “I just took a leap of faith.”

Stackhouse watched some old Nets clips to get a feel for the arena, and what the judges might be looking for. “Hopefully, what I’ve come up with will be good enough to get a callback.”

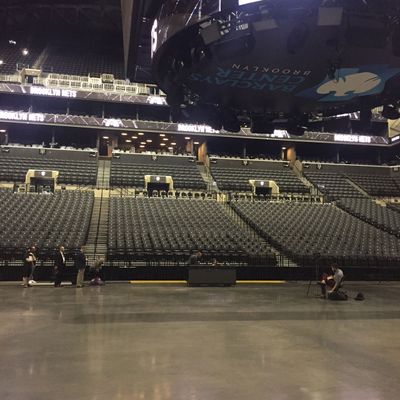

The candidates who do get that callback will have to announce a live game, at Barclays, most likely featuring a community or youth-league team. There’s no set number of potential finalists, but to have a shot at round two, all have to get through this first one, on the floor of the arena, cavernous and intimidating in its emptiness. Contestants are led out in groups of six, and stand, single file, near a small table where each will get his turn to read from the script. On the opposite side of the floor, the judges listen, in a long row far enough away so that the speakers’ heads look like pinpoints. It is, after all, a voice audition.

And here is exactly what those judges are listening to: “Hellooooo, Brooklyn! Good evening and welcome to the Barclays for Brooklyn Nets Basketball presented by Secure Watch 24, the exclusive security partner of the Brooklyn Nets. Tonight, your Nets take on the Dallas Mavericks.”

Over and over and over, like some sad purgatory. Next comes the Dallas Mavericks lineup. If the judges’ show interest, onto the Nets’ lineup. Here, the auditioners let it rip, vibrating their voices, hanging on to syllables. A few promising candidates are asked to watch a game clip on the Jumbotron and call a Nets basket.

So it goes. Number 210, who struggles through a lineup. Number 212, who is feeling a bit more 718. Number 221, Mecuree Robinson, is one of the only women to try out. Perry and Osborne, with numbers in the 230s, have their turns, though the crisp baritones they joked with earlier seem muted on the P.A. Osborne says he wasn’t sure how he did, he couldn’t hear himself. “The echo,” he explains.

Hours in, with dozens and dozens more people to go, the mood in the arena shifts from hopeful to restless. People pace on the edges, listening and judging their competition. There are jobs to get to, and men waver between missing a shift or their chance of a lifetime. The judges seem to give less leeway — though it’s unclear if the candidates have gotten worse, or if hearing “Secure Watch 24 is the official security partner of the Brooklyn Nets” 50 times is finally taking its toll. More auditioners just plain bomb. The disappointed leave the arena, shaking hands or pounding fists.

But most seem willing to stick it out. John Bradford, a 55-year-old from New Jersey, waited with a friend for his turn. He has called games for his daughter’s professional football team, the Keystone Assault. “My nerves get to me pretty quick,” he says. “I’m trying to breathe, take deep breaths, release it slowly.” Bradford has a bushy Santa Claus beard — because, it turns out, he also plays Santa. He has the deep, steady voice of a man who deals with screaming kids. “It’s a long shot, it really is,” Bradford admits. “But if I don’t go, there’s no shot.”

Tony Rothstein, a 36-year-old actor from Ditmas Park, fiddles with his phone. “I could be the face of the Nets, or the voice of the Nets,” he muses. He confesses to having the jitters, but he smoothly shows off his announcer style. “Brook Lopezzzz,” he intones. “I have to make sure I say it just the right way.” Which is? “On the ‘pez,’ on the Lopez.”

That name probably won’t come up, as Lopez was traded to the Lakers in June. But another to consider. “Jeremyyy Liiinch,” says Rothstein, adding a few extra consonants to the end of the point guard’s name. “You don’t want to say it the wrong way. Jeremyyy Liiinnch,” he explains. “You don’t want to say it the wrong way. People might look at you, like, what are you talking about?”

*This article incorrectly stated Robinson’s audition number as 213. It is 221. The story has been updated.