In 2009, Donald Trump bought a golf club in Loews Island, Virginia, and promptly set about refashioning the landscape to suit his needs. He had the courses reconfigured, his name plastered across its walls, and 400 trees chopped down to open up views of the Potomac River, much to the chagrin of local conservationists.

But while the mogul wasn’t interested in conserving trees, he was ostensibly intent on preserving history. As the New York Times reported in 2015:

Between the 14th hole and the 15th tee of one of the club’s two courses, Mr. Trump installed a flagpole on a stone pedestal overlooking the Potomac, to which he affixed a plaque purportedly designating “The River of Blood.”

“Many great American soldiers, both of the North and South, died at this spot,” the inscription reads. “The casualties were so great that the water would turn red and thus became known as ‘The River of Blood.’”

The inscription, beneath his family crest and above Mr. Trump’s full name, concludes: “It is my great honor to have preserved this important section of the Potomac River!”

Alas, the events this plaque commemorates never occurred. The Times was unable to find a single historian of the Civil War willing to vouch for Trump’s claim. And, in an interview with the paper, the reality star all but admitted that he hadn’t determined the site’s historic significance on the basis of expert research, but merely on that of his own intuition (“That was a prime site for river crossings. So, if people are crossing the river, and you happen to be in a civil war, I would say that people were shot — a lot of them”).

Trump had not built a monument to preserve history; he had constructed a prop to lend credibility to a convenient fiction.

On Thursday morning, the president scolded the “foolish” Americans who would rather “change” their nation’s history than learn from it.

Trump’s personal hypocrisy on this subject is expansive. Beyond his own attempts to change Civil War history for fun and profit, the president has also ordered the Department of the Interior to consider the removal or resizing of 30 national monuments — so as to make room for fossil-fuel extraction, among other things.

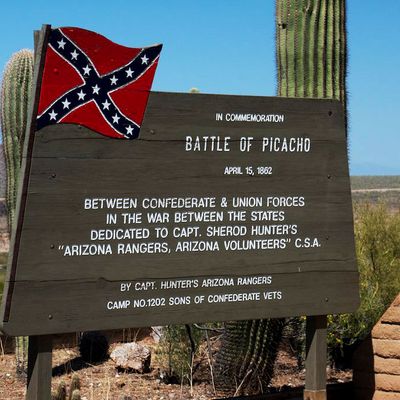

But Trump’s argument wouldn’t be any less ironic were it coming from someone less comprehensively ridiculous. America’s myriad tributes to the Confederacy do no more to promote accurate historical memory than the president’s tribute to the brave imaginary soldiers who died on the shores of his golf course.

Like Trump’s plaque, Confederate monuments were born of a desire to rewrite the past for present convenience. This point should be obvious. If we saw German politicians arguing that there was no tension between upholding the values of their liberal democracy and preserving monuments to Adolf Hitler’s military prowess we would recognize that these officials were trying to distort their nation’s history, not learn from it.

That so many Americans cannot recognize the tension between their president’s endorsements of freedom and equality under the law and his defense of monuments to men who committed treason in defense of chattel slavery is a reflection of our nation’s resilient racism. But it is also a product of the fraudulent history that all those statues of Robert E. Lee were erected to propagate.

In his review of David Blight’s Race and Reunion, historian Eric Foner offers a deft summary of this historical revisionism and its origins:

Two understandings of how the Civil War should be remembered collided in post-bellum America. One was the “emancipationist” vision hinted at by Lincoln in the Gettysburg Address when he spoke of the war as bringing a rebirth of the Republic in the name of freedom and equality. The other was a “reconciliationist” memory that emphasized what the two sides shared in common, particularly the valor of individual soldiers, and suppressed thoughts of the war’s causes and the unfinished legacy of Emancipation. By the end of the 19th century, in a segregated society where blacks’ subordination was taken for granted in the North and South, “the forces of reconciliation” had “overwhelmed the emancipationist vision.” Another way of putting it is that the Confederacy lost the war on the battlefield but won the war over memory.

… Rather than the crisis of a nation divided by antagonistic labor systems and ideologies, the war became a tragic conflict that nonetheless accomplished the task of solidifying the nation. With Reconstruction having ended in 1877, another invented memory – how the South had suffered under what was called Negro rule – was widely accepted among Northern and Southern whites. The abandonment of the nation’s commitment to equal rights for former slaves was the basis on which former white antagonists could unite in the romance of reunion.

Blacks were not the only ones forgotten in this story. Gen. James Longstreet, the Confederate commander who had the temerity to support the rights of former slaves after the war, was excised from the pantheon of Southern heroes. No monuments to Longstreet graced the Southern landscape; indeed, not until 1998 was a statue erected at Gettysburg, where he served under Robert E. Lee.

The South may have lost the Civil War, but it won the battle over how it would be remembered. The statue of Lee that brought white supremacists to Charlottesville last weekend wasn’t built to commemorate the Confederacy’s loss, but Jim Crow’s triumph. Few modern conservatives would defend the statue on the grounds that the resilience of white supremacy in the post-bellum South is worthy of glorification. But they will appeal to the fraudulent history that was written to abet that resilience.

Lee was not an opponent of slavery; he was a slave owner who routinely tortured his chattel and broke up their families. He was not a heroically high-minded military commander, but a general who allowed his soldiers to torture and kill black prisoners of war. Lee did implore his fellow southerners to accept defeat upon the war’s end. But the idea that he unified — or, in the president’s ostensible view, “saved” — America by doing so is obscene. For one thing, Lee’s advocacy for surrender left much to be desired. In the opinion of his former rival Ulysses S. Grant, Lee set “an example of forced acquiescence so grudging and pernicious in its effects as to be hardly realized.” For another, Lee assiduously opposed the only form of reconciliation that would have unified all Americans under the same republican government (the one that would recognize the South’s dark-skinned residents as Americans).

Unlike Longstreet, Lee vociferously opposed the extension of civil rights to African-Americans, imploring Congress not to enfranchise the former slaves, who had “neither the intelligence nor the other qualifications which are necessary to make them safe depositories of political power.”

Lee is not so widely memorialized because he was a uniquely racially progressive Confederate general, but because he was not.

It’s possible that Donald Trump genuinely does not understand this. The “reconciliationist” vision of the war is still taught in our public schools, and fortified by more than 700 monuments to Confederate valor. For the incuriously patriotic white American, it is far easier to accept this narrative, than to confront the implications of its fraudulence.

So long as we live in a nation that glorifies Confederate generals, it will be tempting for (white) patriots to believe that those men fought for something more noble than the Southern elite’s right to enslave dark-skinned human beings; and that subsequent generations built memorials to those generals to celebrate a cause more noble than white supremacy; and that the ongoing presence of such statues in our cities and parks reflects something more noble about our society than its ongoing failure to accept the full humanity of African-Americans.

Unless, of course, such “patriots” march with tiki torches while chanting “blood and soil.”

Which is to say: We can either accept that monuments to Robert E. Lee are an affront to our nation’s highest values or that those neo-Nazis in Charlottesville were right about what those values truly are.

Or else we can keep changing our history to suit the needs of reactionary, rich white fools — and leave that statue of a traitor in Emancipation Park, and that plaque honoring the brave soldiers who drowned in the River of Blood, a few hundred feet from hole 15, at the Trump National Club.