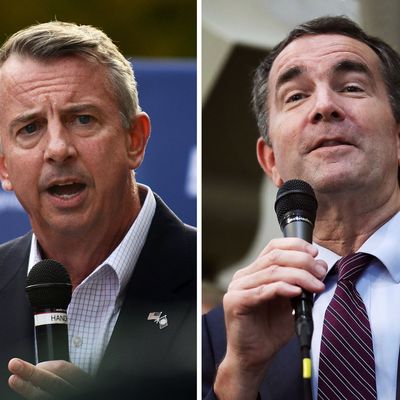

As the nationally important Virginia gubernatorial race went into its final phase, partisans could often pick and choose among polls showing what they wanted to see. At one point in late October, a Hampton University poll showed Ed Gillespie up by 8 points, a few days before a Quinnipiac survey showed Ralph Northam up by 17 points. Was the race really that turbulent, or was some pollster just flat wrong?

For one thing, it’s important to understand that it’s harder to poll accurately in non-presidential than in presidential elections because turnout is so variable. And there are different ways to get at that problem in polls. The most traditional method (known as random digit dialing)

is to take a statistically valid random sample and tweak it with indicators of political engagement associated with likelihood to vote, such as subjective voting intentions and interest in the election.

But some of the polls that do just that are showing the most wild variations in Virginia.

But other surveys (such as Monmouth, Christopher Newport, and Roanoke College) are based on samples that are built from or checked against more objective data on likelihood to vote, such as “voter files.” These are lists of registered voters with addresses, phone numbers, and other data — such as primary voting records — that campaigns rely on and that public pollsters are beginning to use more frequently. Voter-file-based polls in Virginia mostly have shown Northam consistently ahead by mid–single digits, though one Monmouth survey in mid-October had Gillespie up by a point.

There’s no way to know at this point which kind of poll is more accurate; voter-file polls may be more reliable when voting patterns are consistent from election to election, and less reliable when the electorate changes. And current polls are of limited comfort to Democrats even if they do show a steady Northam lead, thanks to a recent history of Democratic underperformance in non-presidential elections in this state.

In 2009, Democrat Creigh Deeds trailed Republican Bob McDonnell by 13.4 percent in the final RealClearPolitics polling average. McDonnell won by 17.5 percent. In 2013, Democrat Terry McAuliffe led Republican Ken Cuccinelli by 6.7 percent in the final RCP average (he also led in the usually reliable Washington Post survey by 12 points). McAuliffe won by 2.5 percent. And then in 2014, Democratic senator Mark Warner led the self-same Ed Gillespie, who’s running for governor now, by 9.7 percent in the final RCP average. Warner won by less than one point.

There are extenuating circumstances that help explain all those Democratic shortfalls: Deeds was running a not-very-competent general election campaign that was especially unattractive to minority voters. Conversely, both McAuliffe and Warner may have been overconfident and/or suffering from complacent Democratic voters who figured Cooch and Gillespie had no chance. Lord knows Virginia Democrats are not complacent this year; they have been fretting about Northam’s campaign for months.

When it comes to Democratic confidence, the jumpy polls aren’t helping at all. It also hasn’t been that long since the ultimate nasty Election Night surprise of 2016 (though the polls then were closer to Hillary Clinton’s popular vote win than people seemed to realize at the time).

If Ralph Northam does win by something like his current 3.3 percent advantage in the polling averages, it will be comforting not only to Virginia Democrats, but for anyone who prefers data —even sometimes flawed and often conflicting data — to reading entrails or trying to measure “enthusiasm” in anticipating what might happen in elections. We should have a pretty good idea by Wednesday what sort of variables tripped up some pollsters, and made others look prophetic.