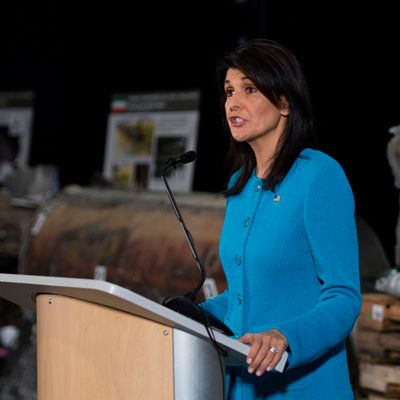

When U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley on Thursday presented what she claimed was irrefutable evidence that Iran had supplied a missile launched at the Saudi Arabian capital by Houthi rebels in Yemen last month, it was hard not to recall the last time an American diplomat stood before the U.N. with evidence that a rogue Middle Eastern state was engaged in proliferation of dangerous weapons.

As it turned out, then–secretary of State Colin Powell’s 2003 speech explaining the Bush administration’s rationale for going to war with Iraq was based on lies and fabrications, and, of course, Iran says Haley’s evidence is fabricated as well. Iran’s proxy relationship with the Houthis is well-known, but the U.N. itself is not as sure as the U.S. seems to be that the two short-range ballistic missiles fired by the Houthis were Iranian-made, while some experts suspect Saudi Arabia of overstating Iran’s meddling in Yemen, the better to justify its own.

For missiles that (as Haley put it) “might as well have ‘Made in Iran’ stickers on them” to literally fall into Saudi Arabia’s lap is mighty convenient for Saudi Arabia’s efforts to paint Iran as Mideast menace No. 1. Are we sure we’re not letting ourselves get dragged into an ill-advised Saudi scheme for a decisive confrontation with their regional rival? Haley’s claim that Iran is violating U.N. resolutions via its Yemeni proxy is a good deal more credible than Powell’s yarn about Saddam Hussein buying yellowcake uranium from Niger. Nonetheless, the conspiracy theory that the Saudis made the whole thing up will find an audience in the Middle East’s already-weaponized fake news environment.

Also complicating Haley’s claim that Iranian weapons “are turning up in war zones across the region” — or at least the moral authority of the United States to complain about that — is that our weapons and those of our allies tend to do the same, both intentionally and otherwise. It is a little hypocritical to demagogue against Iran for backing its preferred factions in the Yemeni civil war while Saudi Arabia besieges and bombs that country with Washington’s backing, the weapons the U.S. dumps in Syria and Iraq keep ending up in the hands of extremists, and private Saudi money funds at least as many jihadists across the Middle East as Iran’s Revolutionary Guard does.

But what really makes Haley’s speech reminiscent of Powell’s is that the latter was a crucial step toward war, whereas the former, well, could be.

With the support of their Cold War allies, Saudi Arabia and Iran have been engaged in a regional cold war of their own for some time, which has had few benefits for either side but has resulted in a tremendous amount of death and suffering throughout the Middle East. Lately, Saudi Arabia and its frenemy Israel have been ramping up their rhetoric on the threat Iran poses to the region, suggesting (but not quite saying) that it might be time to turn this cold war hot. Haley said the U.S. intended to “build a coalition to really push back against Iran” — but is it a coalition of the willing?

On its own, Haley’s presentation might read as an argument for renegotiating the agreement over Iran’s nuclear program or reinforcing international sanctions against the country, but taken with everything that has gone on in the past few months, it is not outside the realm of possibility that the Trump administration is gearing up for a direct military engagement with Iran, with the U.S. serving as a bridge for awkward partners Israel and Saudi Arabia.

Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu was an outspoken critic of the Iran deal and the Obama administration’s overall effort at rapprochement with Iran, and has long advocated for an international coalition to deprive Iran of the means of producing a nuclear weapon, by force if necessary. Israeli right-wingers like Naftali Bennett are loudly complaining of Iranian aggression through proxies like Hezbollah and its presence in Syria. Now that ISIS is on the retreat in Iraq, U.S. diplomacy there is shifting toward a new priority: containing Iranian influence. Saudi Arabia has been vying with Iran for influence in Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Palestine for many years now, and recently has taken to planting anti-Iran propaganda in publications as prestigious as The Atlantic, along with stunts like having Lebanese prime minister Saad Hariri fly to Saudi Arabia to resign his office, citing Iranian threats on his life, then later withdraw his resignation. Even France’s foreign minister says Iran is trying to create an “axis” of influence from its western border to the Mediterranean Sea.

This all sounds a bit like a group of countries laying the groundwork for war with Iran. Compounding the suspicion that a U.S.–Iran conflict is in the cards is that the administration has identified checking Iranian expansionism as a goal of its Middle East policy. President Donald Trump decertified the nuclear deal in October, opening the door for Congress to either fix it, rescind it, or kick the can right back to him. Preoccupied with robbing the poor to pay the rich, Congress chose the third option and let its deadline pass. The ball is now back in Trump’s court, where he may effectively cancel the agreement at any time by re-imposing sanctions. The increasing marginalization of Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, who has been trying to uphold the agreement, may show which way the wind is blowing.

Trump’s decision to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and reaffirm plans to move the U.S. embassy there was also seen as a sign that the regional coalition against Iran has already formed up. Even though critics of the move rightly observed that it would make it more politically challenging for Arab leaders to join an American-Israeli alliance against Iran, the cynical (and, unfortunately, probably correct) view is that these leaders will voice outrage at Trump’s provocation but do little else, and will fall in line with U.S. policy priorities when the time comes.

Little wonder, then, that the International Crisis Group is warning of a high risk that the U.S. and Iran come to blows over the Yemen conflict. It’s not entirely clear how the Trump administration would juggle full-scale wars with both Iran and North Korea. Nor can we predict exactly how Russia, other regional actors like Turkey, or the various non-state actors and terrorist groups of the Middle East would respond to a march toward war with Iran. Hell, we don’t even know if the Trump administration is gunning for that outcome, but it sure looks like it.