Hope Hicks plans to depart Washington by Good Friday, over a month after she resigned as the White House communications director on February 28. She will leave behind a press operation that is inherently broken, rife with scandal and petty divisions that have only worsened amid the cyclical staff sheddings that have defined the first 14 months of Donald Trump’s administration.

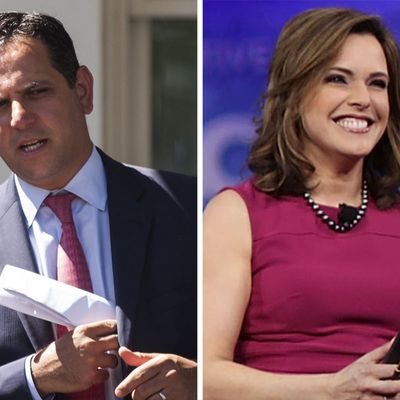

The race to fill the Hicks void is a clandestine parade of all the worst human impulses. Among the potential hires mentioned by Trump in conversations with aides in recent weeks are former Fox News executive Bill Shine, who reportedly isn’t interested, and Kellyanne Conway, who reportedly is. But administration sources told New York that, whoever the job goes to, the real story is the bloodletting between two early front-runners: director of strategic communications Mercedes “Mercy” Schlapp and Treasury Department spokesperson Tony Sayegh, both former Fox News contributors.

White House officials told New York the view from the inside is that Mercy wants it most, and is campaigning for the job with the assistance of her husband, Matt Schlapp, a lobbyist and frequent presence on cable news who chairs the American Conservative Union, while Sayegh is a competitor because he was well-liked by Hicks, whose recommendation the president is expected to weigh heavily. When anonymous sources began sprouting weedlike in the conservative press to go after Sayegh, the Schlapps were blamed. And their perceived ruthlessness had a perceived profit motive: the year that Mercy joined the administration, Matt’s lobbying firm saw its income nearly double.

“How’s that for fucking hubris?” a former senior White House official told New York. “The Schlapps have literally turned off so many people. Access to power has turned them both into fucking monsters.”

Hicks was the third communications director, after Michael Dubke (March–May) and Anthony Scaramucci (July–also July). If you count Sean Spicer, who held dual roles as the press secretary and the communications director during bursts of communications directorlessness, Hicks was the fourth communications director. And if you count Jason Miller, who was supposed to be the first communications director but ended up not entering the White House, Hicks was the fifth communications director. The job was hers for a Trumpian record of five months.

Seeking the job now, knowing its recent history, is something of a self-destructive act; it’s unlikely anyone will replicate Hicks’s singular importance, and the higher you climb in the Trump White House, the quicker you’re killed off. Yet the appeal of the senior title and promise of access to the president is strong, even if who the president is means that the substance of the job is irrelevant: how do you devise messaging for Trump, who will blow up the strategy without warning with a single early-morning tweet? “One hour you’ll be talking about immigration reform. The next you’ll be talking about the NFL. The next you’ll be talking about gun policy. The next you’ll be talking about tax cuts. And then, you know, circle back around to who lied on Morning Joe that day,” a second former White House official told New York, comparing the experience in the press shop to being, “on speed.”

And then there’s the fact that everyone’s always trying to kill everyone else.

“In some aspects, it’s worse than people even realize,” a current White House official told New York. “It started early on, when it was very factionalized with the RNC individuals versus Bannon’s versus Jared’s. All of that infighting just carried over. It’s a never-ending cycle.”

The official added, with a laugh: “It wouldn’t be this White House if everyone inside wasn’t fighting all the time.”

The Schlapp-Sayegh drama has its origins in tax reform, the only successful policy rollout of the Trump presidency so far. From the introduction of the plan in early November to the bill signing in late December, it took just seven weeks, scoring Trump a big-league legislative victory just as his first year in office came to a close.

Led broadly by the since-departed economic adviser Gary Cohn, it included select staffers from the national economic council, legislative affairs, political affairs, communications, and other White House departments. Sayegh was brought in to work alongside Hicks in her office, which shares a wall with the Oval. The time and attention the project absorbed, and the president’s awareness of it, bred what several sources in the administration referred to as “resentment” from those not involved, in particular from Schlapp. “It was the biggest thing the White House was doing,” the official said. When it was successful, that only created more resentment.

“She probably came in thinking she’d have a lot of access to the president,” an administration official told New York. “And then you get there, and find you don’t interact with the guy at all and you’re not working on the biggest issue.” Instead, Schlapp cultivated the impression that she was to Chief of Staff John Kelly what Hicks was to the president, but sources described uncertainty or even skepticism about the true state of their relationship even as they cautiously interpreted her directives as coming, in one way or another, “from the Chief.”

But worse than isolation from Trump for Schlapp’s prospects as the president’s new right-hand woman was isolation from the original right-hand woman. Hicks liked Sayegh, and by extension, those who liked Hicks liked him, too: Josh Raffel, another senior communications official who acted as a spokesperson for Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner, and Javanka themselves. (Both Hicks and Raffel had previous relationships with the couple, having worked for a New York PR firm that repped the Trump Organization and Kushner Companies; Hicks eventually departed the firm to join the Trump Organization itself.) When Hicks resigned from the White House (shortly after Raffel resigned), she and her allies encouraged Sayegh to consider taking her place.

“Usually a communications director focuses on long-term planning and policy rollout,” another administration official said, “and if you think about it, tax reform was the only rollout that we achieved in a significant way.” Sayegh had the benefit of being associated primarily with a rare high-profile case of something going well for Trump from a messaging perspective during year one.

But on paper, Schlapp was a more obvious choice: she’d already replaced Hicks once before; her title, director of strategic communications, was one invented specifically for Hicks at the beginning of the administration, before she stepped in to replace the Mooch last summer. Not that it really mattered what Hicks was called. She was the president’s closest and longest-serving political aide, and she occupied an office within earshot of his own. She acted not just as the barrier between Trump and the press corps, but between Trump and other members of the White House staff. This was particularly true of press officials, who relied on Hicks for coherent predictions or expressions of his views, and who, with her there, often had no reason to speak to him themselves.

When Hicks finally became vulnerable — amid her involvement in the various Russia investigations and Degrassi: The Next Generation–meets-Homeland drama in her personal life — Schlapp saw opportunity, sources said. Speaking to New York last month, Schlapp denied this characterization from her colleagues; she said she was hurt by the rumors. “I called Hope right away and was like, ‘This is ridiculous. You know where my heart is and where we work together.’ I mean, she is someone who I incredibly value,” Schlapp said. “I feel like Mother Hen here a lot of times, and I’m very protective of my little — you know, the team.” But a former White House official said that was laughable: “She went after Hope with a fucking full knife right away.” Beloved baby chick or Kentucky Fried, the maneuvering to fill Hicks’s position was cannibalistic from the start.

Things escalated earlier this month, when the fighting spilled into public view with a story in the Washington Examiner that painted a grim portrait of Sayegh. The Examiner reported that Sayegh “has a tendency to ‘delegate too much,’ to boss people around, and to manipulate others for his own benefit,” according to “sources close to and within the administration.” The Examiner added that “one administration official” said these negative characteristics came into sharp relief, “in Sayegh’s interactions with female staff.” According to a source the Examiner described as “a person familiar with conversations about the communications director search,” Sayegh is known in the White House as “a terrible bully.” The Examiner offered no examples of behavior to support the allegations.

Internally, the article was viewed as a hit job — and not a graceful one. Four sources in the administration told New York they believed it was obviously Schlapp’s handiwork.

The American Conservative Union, where Mercy’s husband is chair, is an influential group that organizes the annual Conservative Political Action Conference. Like many publications of its ideological ilk, the Examiner has ties to CPAC; its editors and contributors have spoken at the confab over the years, and as Trump has subsumed the right-wing movement, the publication has documented CPAC’s evolution with vested interest. The foundation belonging to the Examiner’s owner, Philip Anschutz, helps fund the ACU. The day after Hicks resigned, the Examiner ran a column titled, “Mercedes Schlapp should replace Hope Hicks as White House communications director.” It concluded, “Hope Hicks was rarely seen by the media and that damaged her effectiveness and the public’s interest in media access. Mercedes Schlapp can do better for her boss and the American people.”

“It’s contaminating her candidacy,” one administration official told New York. A source close to the White House added, “I think she blew herself up before getting the job.”

The Examiner, incidentally, reported that, when he was asked about the possibility that Mercy could be the communications director during a TV appearance, Matt Schlapp responded by saying she would be “very open” to whatever Trump wanted her to do. “It’s almost like she’s running her own surrogate operation internally and externally,” the official said. “She’s running a shadow comms shop.”

According to administration sources, Schlapp has assembled internal support in large numbers, but not among people who are decision-makers. “She’s got a conglomerate of junior and mid-level staffers she’s trying to take under her wing,” one White House official said, explaining that her kindness is seen as a cynical ploy, like “a grassroots operation” that works only on staffers too green to “see through this shit.” A second official said that Sayegh “has been a little more strategic, and he has some pretty big names behind him.”

The allegations against Sayegh — that he’s a “bully” who treats women in the workplace worse than men — were seen as a leap beyond standard self-promotion, and particularly brutal even for Washington, considering the current political and cultural environment as it relates to women sharing professional space with men. “That’s coded language for something more,” the official said, adding, “that Tony piece is upsetting. I haven’t really thought about why, I’ve just been sitting here shaking my head that it’s happening at all.”

The official added, “It sounds to me like she took offense to something he was doing and she’s trying to get back at him. I’ve never seen him treat a woman differently than he treats a man and it shows how recklessly they’re playing with people’s lives.”

Sources inside and outside the administration said that the Schlapps suffer from a lack of subtlety that reveals not only the methods used to reach an end, but their motives for wanting the end in the first place. When Mercy entered the White House, she left Cove Strategies, the lobbying group where her husband remains a principal. From 2009 to 2016, according to data from OpenSecrets, Cove Strategies earned between $390,000 and $640,000 annually, lobbying on behalf of companies like Comcast, Walmart, Verizon, the Motion Picture Association of America, Dow Chemical, Koch Industries, and so on. In 2016, Cove Strategies earned $640,000 lobbying for five companies. But in 2017, the year Mercy Schlapp became a Trump official, those numbers almost doubled: Cove Strategies earned $1,030,000 from nine clients.

There is an “impression internally,” according to a White House official, “that she’s using this experience to enrich her family.” Another White House official had a more direct accusation: “Cove Strategies should change its address to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. The president doesn’t know it, but they’ve set up their headquarters in the West Wing of his house, rent free.”

Angela Flood, a principal at Cove Strategies, said that the impression described by the officials was “mistaken,” adding, “I’m wondering if maybe they have an agenda. I don’t know why somebody would make those accusations.” Flood dismissed Matt Schlapp’s visits to the White House as standard, and unrelated to his business. “I can tell you that we have gone to great lengths to draw very bright lines between anything that happens at Cove and Mercy,” Flood said.

After telling New York that Schlapp and Sayegh wanted to be interviewed for this story, the White House instead provided New York with a statement from deputy press secretary Hogan Gidley: “This palace intrigue nonsense is all ridiculous. Like at any workplace, Tony and Mercy interact in an entirely professional manner. They work closely together and make great things happen for the President’s agenda — and will continue to do so.” The White House also told New York that Schlapp and Sayegh have plans for some kind of social interaction this week, but couldn’t say what those plans were or when exactly they would take place. First, they said it was a dinner. Then, it was a lunch.

But ridiculous nonsense matters a lot in the Trump era, and this episode of fighting has staffers in a state of existential crisis. “One component is always trying to do their jobs, and one component is trying to keep some semblance of peace, and one component is where all the chaos goes,” a White House official said. “At some point we’re all going to need therapists or psychiatrists.”

“In this White House, the comms shop is 100 times more important than the policy shop. The comms shop is what Trump lives for — that’s why he’s on Twitter all the time. Policy is not relevant to him, he doesn’t care. What he cares about are stories,” a second former White House official told New York. “The president of the United States walked into lower press and put his head in there,” the former official added, referring to a recent incident when Trump walked into the briefing room to tell reporters he’d have an announcement soon. “The president of the fucking United States — he’s like an assistant press secretary!”

But as the issue drains time and energy from the staffers fighting and from the staffers tasked with convincing the press that no staffers are fighting, it’s faded from Trump’s mind. For the next few hours, at least, Hicks is still in Washington.