This chat will run in the Daily Intelligencer newsletter, which combines a digest of the stories you care about with exclusive political commentary that you won’t find on the website. To subscribe to the newsletter, click here.

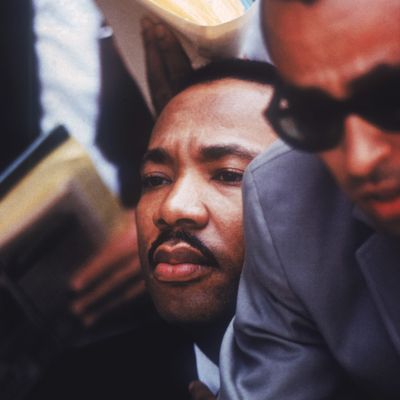

I’m your humble host and editor Ezekiel Kweku, and today I’m talking with three members of New York’s politics team — Jonathan Chait, Ed Kilgore, and Margaret Hartmann — about the legacy and memory of Martin Luther King Jr.

Ezekiel: What do people *forget* about Martin Luther King Jr.? What’s missing or de-emphasized from the public’s memory when they think about his life, mission, and legacy?

Margaret: I think for many he’s been boiled down to an almost neutral figure who preached racial equality and gave good quotes you can post on your social-media page.

Jon: The degree to which he was a political actor, a shrewd tactician, engaged in negotiation and boundary-pushing, not only a quote unquote moral leader.

Ed: The obvious thing is his broader economic and social vision, and its radicalism. The less obvious thing is how much he was hated by so many white southerners before his assassination. The latter is worth remembering because the ideological (and in some cases, biological) descendants of those who hated him now tend to view him as a race-neutral, quasi-conservative.

Ezekiel: White northerners, too! King said once that the mobs in Chicago were more hateful than the ones in the South.

Ed: True. I’m just describing what I know personally, as a cracker who was of sentient age when he was assassinated.

Ezekiel: I would love to hear any recollections you have from around that time if you’re willing to share.

Jon: What time? 1968? I was born in 1972.

Ezekiel: I meant Ed, lol.

Jon: Ed, did you ever meet Abe Lincoln?

Ezekiel: Ed actually lent Honest Abe ten bucks and never got it back.

Jon: Haha.

Ed: (Ignoring Jon). I happened to be visiting some of my rural relatives right after the assassination. The “nicer” among them were unhappy that so many Yankee politicians attended MLK’s funeral. But I mostly remember my sweet “old maid” great aunt saying that if she could find the assassin, she’d take him in and hide him and feed him and care for him the rest of his life.

Jon: Wow.

Margaret: Damn.

Ed: This is a woman who never much missed a Sunday in church. And this is what MLK was dealing with. The Letter From a Birmingham Jail was aimed at the “nice” people of the South.

You can say his legacy was turning people like this — or their descendants, anyway — into lukewarm supporters of desegregation. Or you can say none of them ever quite got it.

Ezekiel: What were the ramifications of King being assassinated when he was? It’s always hard to think through counterfactuals, but how do you think that changed the course history would take?

Jon: I think King probably would have become a less popular, more partisan figure had he lived.

He would not have become a civic icon — I wonder who or what would have filled that space, if anybody. Would there be a “neutral” symbol of civil rights, essentially a modern founder?

Ezekiel: It certainly would have been harder to elide late period King’s anti-war, anti-imperialist, and anti-capitalist message if he hadn’t died young. It seems possible that that symbolic role in the popular memory might not have been filled at all.

Ed: I agree the Poor People’s Campaign would not have been much more popular with King leading it than Abernathy.

Margaret: I’m imagining Fox News going after an 80-something MLK and shuddering.

Ed: On the other hand, it’s not clear the civil-rights movement would have fragmented quite the way it did, with SNCC becoming a “Black Power” stronghold.

Jon: The movement was already quite fragmented when King was alive. It’s not only the right that has engaged in revisionism about what King meant. The left, too, has smoothed over the differences. Many people to King’s left loathed him in his time.

Ed: Yes, but he had a way of holding it together. Even Malcolm X, before his own assassination, was reaching out to King.

Ezekiel: Maybe John Lewis might be the guy. Or perhaps Andrew Young. Both politicians, but that could even make them more palatable.

Ed: I agree that Lewis, who was actually well to King’s left during his life, could have been a transcendent figure. But he largely shunned the limelight back in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Ezekiel: Yeah, I’m thinking more about who would be the icon representing the civil-rights movement in memory rather than who could have/would have replaced King’s actual role after his death.

Jon: Really, almost any great politician ultimately becomes memorialized as a non-politician in history. And King wasn’t a politician per se, meaning elected official or candidate, but he was engaged in politics.

Ed: Jon’s right, of course: there are progressive politicians, and then there are social-movement leaders who push the politicians. King did cross the line now and then. Quick aside (yes, another old guy thing): in the six Democratic National Conventions where I worked in the script/speech operation, the only time I was really moved was by John Lewis in 2008. He also went around the rehearsal room thanking everyone there. Just the nicest pol I’ve ever met.

Ezekiel: A related question: who are King’s political heirs?

Margaret: According to social media on MLK Day, multiple GOP politicians.

Jon: My thought is that it’s hard to identify his heirs. You never know how somebody will evolve over time. People have taken sharp turns in their thought as they age, sometimes unpredictably.

Ed: The immediate heirs have been a mixed bag: Andrew Young, Hosea Williams, Jesse Jackson. None approached King’s moral authority, though Young and Jackson were skillful pols.

But you can make the argument — actually, many have — that Obama was the Joshua to King’s Moses.

Margaret: I’d agree with Obama on moral authority but he couldn’t (didn’t?) fully engage with the protest aspect of fighting for racial equality.

Ezekiel: I think there are similarities between the flattened memory of King and ’08 candidate Obama, but I don’t know about between the actual men. I feel like tightest through lines we have from King are Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition and William Barber’s Moral Mondays.

Ed: I’m a huge fan of William Barber, and agree he is King-like in many respects. The question is whether King’s “heirs” are found among the pols he enabled, or the prophets whom he inspired.

Margaret: Obviously Obama was fighting to advance equality from a policy side, but as president (and particularly the first black president) he had to stay more neutral in the Black Lives Matter movement than perhaps he would have liked to.

Ed: You’re right: Joshua had a different set of circumstances and constraints than Moses.

Ezekiel: Where, if anywhere, do you disagree with MLK?

Ed: This is a hard one. I’d say this: I think we now understand the weaponization of the Declaration of Independence that King and so many civil-rights folk participated in is a two-edged sword, now that it’s being used by conservatives to undermine democracy. Maybe the 14th Amendment was a stronger pillar on which to rely.

Margaret: Honestly, the conversation has made me realize that I don’t have a nuanced enough understanding of MLK to disagree with his message. I’m guessing I’m typical of many people my age that I don’t have a deeper understanding of what he actually did, but it’s also embarrassing. I’m 34 and capable of cracking a book, but I am concerned that we do a poor job of educating kids on the reality of the civil-rights movement.

Ezekiel: I think we would all do well to deepen our understanding of King and the civil-rights movement, and more broadly, the lives of black people in this country between the Civil War and 1968. My biggest disagreement with King — maybe it is less a disagreement with him than it is just a recognition that America has changed over the past 50 years — I don’t think the American conscience can be shocked into true repentance anymore. I think it is callused and atrophied. I’m still thinking through the consequences of that.