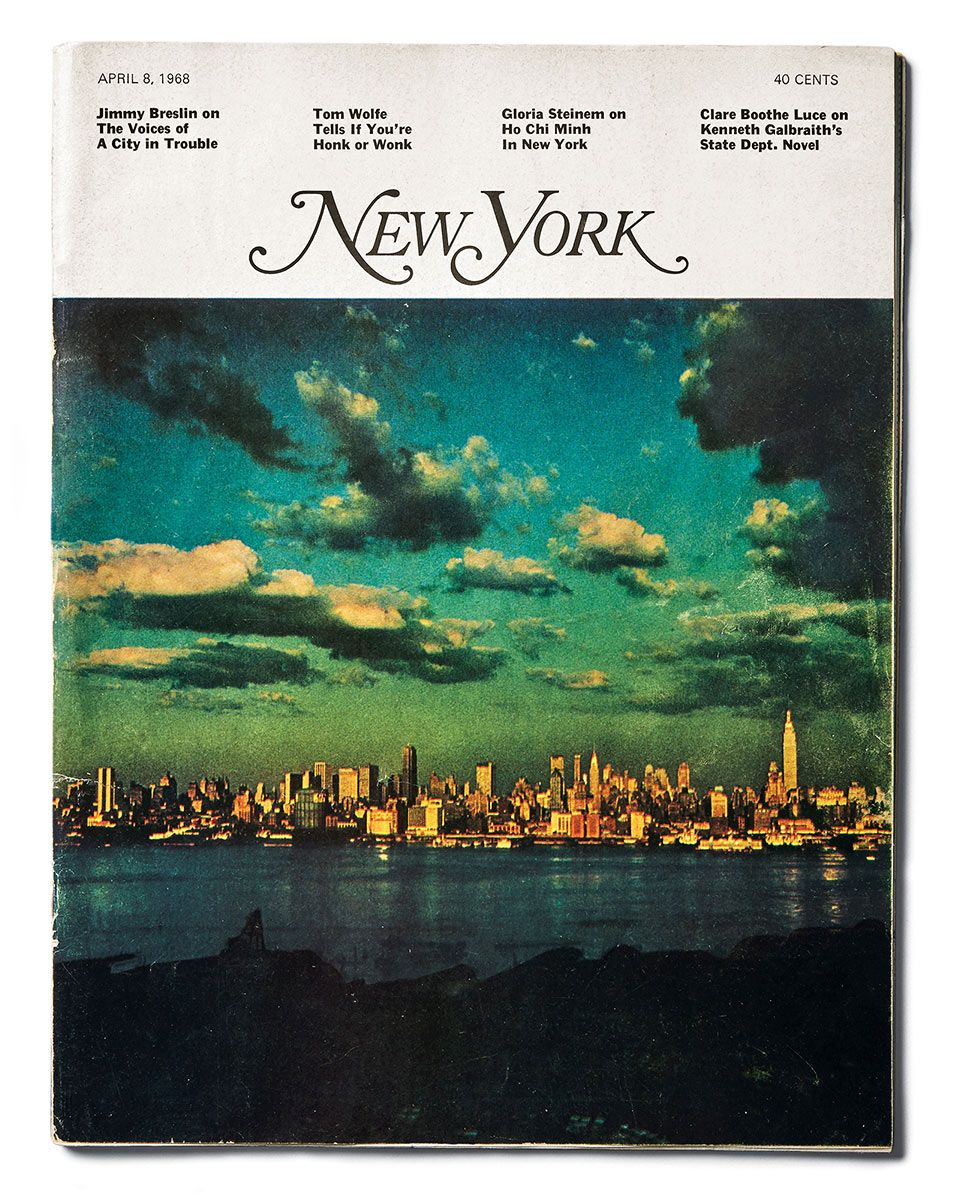

The cover date of New York’s first issue was April 8, 1968. To mark our 50th birthday, we present this oral history of the magazine’s early days, excerpted from Highbrow, Lowbrow, Brilliant, Despicable: 50 Years of New York Magazine.

The New York Times, May 8, 1967: “Hope for starting the New York magazine, which had been a Sunday supplement for The World Journal Tribune, as an independent publication, was disclosed yesterday by Clay Felker, who had been editor of that magazine and the Book Week supplement. Mr. Felker said he was trying to raise capital for a new enterprise, teaming up with Jimmy Breslin, columnist; Tom Wolfe, writer, and Milton Glaser, art director for Push Pin Studios … Mr. Felker said he had asked Matt Meyer, president of the World Journal Tribune, for the right to use the title.”

Milton Glaser (design director and columnist, 1968–1977): I must say how innocent we all were about what a magazine should be. But in some cases that kind of innocence is a benefit. You don’t know what to do, so you invent something.

Gloria Steinem (contributing editor, 1968–1971): Clay and I had countless lunches that we referred to as “tap dancing for rich people.” We were pitching the essence of New York — persuading New Yorkers that they were important enough and universal enough to have a magazine.

Tom Wolfe (contributing editor, 1968–1977): Jock Whitney [who had owned the Herald Tribune] had agreed to sell the name New York for $6,500, but Clay couldn’t even come up with that. He finally borrowed it from a writer, Barbara Goldsmith.

Glaser: The prevailing spirit was, we’re all in the same boat together. That means you could repair the leaks, it’s going in the wrong direction, whatever — but it’s never about tearing it down. Personally I’ve always felt optimistic about the city, because of this idea that it’s a place where anything can happen, and that you can’t anticipate what that will be. The city is too complex to ever be sort of epitomized by a single perception. I mean it’s the worst, it’s the best, it’s the least. It’s the most terrible people, the best people. All of that at once.

Steinem: We had a lot of other names, some of them quite funny. Tom wanted to name it The New York Moon, because he had this vision of sending trucks to deliver it to newsstands, going too fast on purpose, with a big banner that said THE MOON IS OUT.

Gail Sheehy (contributing editor, 1968–1977): One of the unique aspects of this is the relationship between Clay and Milton. Clay was very much a kind of Upper East Side debonair man-about-town, living in a big duplex, and Milton was very much downtown, an artist in turtlenecks and very long, wild hair. Clay had a more hair-trigger temper, and Milton was more the rabbi who worked things through. But their sensibilities were totally in sync. They both saw beyond the normal conventions of magazine journalism.

Glaser: We knew that we certainly couldn’t beat The New Yorker at its game. We always thought of New York as being somewhat more working class. We tried to avoid issues of elitism or talking down to our audience, and wanted to be just one of the guys, the people who made it.

Charles Denson (office assistant and staff photographer, 1968–1977): Clay was obsessed with power and how things really worked in New York and what was going on behind the scenes, and that was the magazine’s strong point.

Richard Reeves (writer, 1971–1977): The New York Times covered the city as government, and New York covered the city as millions of people.

Alan Patricof (board member, 1968–1971; chairman, 1971–1977): I really respected his talent. His ability to catch trends — you look at the number of people he brought to the magazine, where all those people have gone — that’s no accident.

The New York Times, February 1, 1968:

“NEW YORK MAGAZINE TO APPEAR APRIL 8: New York magazine, the Sunday supplement of the defunct World Journal Tribune, will appear as an independent weekly on April 8, Clay Felker, its editor, announced yesterday. Mr. Felker said that production problems had set back the scheduled publication date of the first issue, which had been set for March 1. There is no plan to change the name of the magazine, he said, despite a protest by the New Yorker, the 43-year-old magazine of humor and commentary, which has threatened legal action against the forthcoming weekly.”

Steinem: The first issue of any magazine is, in my slender experience, a kind of heart attack, because systems are not in place yet, and there’s been lots of question about what should be in the issue, and everything’s coming together at a fever point of inefficiency.

Sheehy: Gloria came up with the idea of writing about Ho Chi Minh’s travels in New York and other parts of the United States as a young man. When she showed up late clutching her story, Clay grabbed the manuscript and without a glance handed it off to a messenger to take to the printer. She said, “How can you run a story without fact-checking or something?” He said, “It’s here.”

Steinem: That’s almost true. I believe that that piece was at least three times as long. So he didn’t change it, but it was drastically cut for space. But I have to say that Clay did not keep me from sending off Western Union telegrams to the leader of our enemy in a war, to try to fact-check Ho Chi Minh.

Glaser: I tell people this, and they say they don’t believe me. But finally we put together an issue and we did everything that was required, and when we got it out of here none of us were ready for the fact that next week there was going to be another one. Suddenly we realized that the job wasn’t done. “Again?”

Deborah Harkins (editor, 1968–1995): But it was collegial, and funny. We had a music editor, Alan Rich, and a switchboard person named Marion. Alan would always rush silently from his desk and come over to Marion and wrestle her to the floor. She kept going, ‘Oh, Alan. Oh, Alan.’ One day Clay came out of his office and stepped right over them and went down the stairs.

Glaser: The most difficult part was the transition from the old insert to a freestanding magazine. You can see, in the first year particularly, significant remnants of the old magazine. There was not accountability between the covers and the contents. You found a picture, it was about New York, and we were saying, “That’s sufficient. We don’t have to talk about what’s inside or anything else.”

Walter Bernard (art director, 1968–1977): A parking meter with a glove on it, the doorknob of the Plaza Hotel — all of those very beautiful things that were in the tradition of the Herald Tribune. Except people didn’t want to pay 40 cents for that.

Glaser: We discovered that we had to be more aggressive, more visceral.

The magazine ran on a shoestring budget, out of the fourth floor of Glaser’s own Push Pin Studios building on East 32nd Street.

Bernard: Do you know where our typesetter was, for the first six months? Philadelphia. We had messengers going back and forth.

Glaser: There’d be people replacing letters, cutting in an e because there was a misprint.

Bernard: Because you couldn’t send it back to Philadelphia to get an e fixed.

Glaser: It was the most perversely inappropriate way to put a magazine together you could imagine and yet somehow we did it every week.

Sheehy: You would arrive at the top of the stairs out of breath. The messengers, you always thought they were going to have a heart attack before they got into the newsroom. I had to borrow a desk.

We had to wait until somebody went out to lunch.

Harkins: I sat under the skylight, which would drift snow down over us in the wintertime. We would sit there with gloves on to do our typing.

Bernard: We complained to the landlord, but he was ruthless.

Glaser: I wasn’t going to give them a thing. [Laughs.]

Denson: There was a row of flat files in the center — Byron Dobell and Shelly Zalaznick and Milton and Clay would be standing around them discussing a story. It wasn’t like an editorial meeting at a newspaper or something where you’d sit around the table.

Sheehy: Clay didn’t really pencil-edit. I mean, his way of pencil-editing — he’d say, “You’ll need this on page three.” He’d say, “This guy is the real story, is the lede.”

Reeves: Clay was a great actor, when he was trying to push someone around — he’d be on the phone yelling at people as if he was totally out of control, and then he’d hang up the phone and turn and say, “Now, what were you saying?”

Patricof: People who were in my office then remember Clay calling me up and shouting at the top of his lungs. What I subsequently learned was that he was doing this, to a great extent, for the people sitting around him in the open office, so that they could hear him in this aggressive fashion, demonstrating his macho or whatever. I’d just put my hand over the speaker.

Harkins: The walls went only partway up, so we could hear everything. He would yell, mostly at Milton Glaser, and Glaser would boom back at him. We called them the Twin Towers.

The magazine’s ability to generate buzz also made writers eager to join up.

Sheehy: The fact that it was tiny and daring and on the edge is what made us believe in it. I mean, there wasn’t anything else out there that was anything like it. The thing that you got back from people was not always Oh, I loved your story — it was, How could you say that?

Steinem: The initial group of writers had stock, a small amount — about $15,000. The reason I remember this is, I put it up for bail. You know the old women’s prison that was in the Village? Well, there were friends in that prison that needed to get out for medical reasons — abortion reasons, actually. Clay got angry at me. He said, “You can’t do that!” But he didn’t keep me from doing it.

Sheehy: Jimmy Breslin and Tom Wolfe were constantly doing sociopolitical commentary on street life. With Breslin it was all about pimps and prostitutes and kneecappers and bail bondsmen, these great characters he created, and then Tom was constantly investigating status — such an important part of New York, with so many levels and sublevels. Tom’s piece “The Me Decade” — he was such a master of language and satire, and that took up most of the issue. I remember one of the biggest thrills of my life was to get a personal note from Tom Wolfe, typed, with his big flourishing signature, congratulating me for writing about “caste and class in the hustling trade.” Because I was writing from the streetwalkers up to courtesans.

Reeves: I was doing pretty well at the Times, and Clay came up to me and said, “Why aren’t you writing for New York Magazine?” I said, “Well, nobody ever asked me.” I didn’t take Clay seriously. I mean, New York was nice, but I wasn’t about to move. Then, a few months later, I lived on West 11th Street, and there was a soup-and-sandwich café there, and Milton Glaser, who was then writing “The Underground Gourmet,” did a piece on it saying this stuff was great. I looked out the window, and there was a line around the block, and I thought, Oh, people are really reading this stuff.”

Frank Rich (writer, 2010–present): I was in college, and I was captivated by it. The New York part of it was fascinating to me because I had always had a childhood fantasy of moving to New York, and Felker’s New York brought home the glamour and the conflict and what we would now call the buzz of New York — the conversation about politics and culture — as nobody else did. It was so different from, at that time, the unbelievably dull and obligatory New York Times Magazine. It had ballsy critics — John Simon, Judith Crist. And a jazzy package that was so original and energizing in contrast to any conceivable competitor. And Nora [Ephron], who I’d later become friends with, but who I was already reading when I was in college.

As the city has changed in the decades since 1968, so has New York — one not just reflecting but creating the other, in a cycle of reinvention.

Michael Wolff (columnist, 1997–2004): It came to define, precipitate, predict the Manhattan that was to become. Clay basically created the yuppie — his proposition was a straightforward one, that you could buy yourself into the class you wanted to be in. And he created New York as a consumer city. There was a time when people didn’t go out to restaurants here. And then New York Magazine came along and redefined what restaurants were, what public life was in New York, redefined who could be part of that life, and what the methods were to get there. The reconstruction of the urban environment which begins about then and comes to fruition in the ’90s is a New York Magazine construct.

Michael Hirschorn (executive editor, 1994–1996): There’s something about New York Magazine that people really care about. It’s still the case that New York Magazine has a unique impact that has not changed.

Adam Moss (editor-in-chief, 2004–present): These days, as New York City continues to be a stunningly successful export of itself, New York has become more national and international, chronicling or reflecting the evolution of urban life in cities everywhere — which have come to look more and more like each other. New York has become a set of publications in every medium, including live performance, and its subject has become not just New York but cities everywhere, city life everywhere, the urban creature everywhere. And in America in the Trump years, which has really found itself very much divided between city and country, that turns out to be a huge and interesting and even important canvas.