On a sunny afternoon in April, Joe Womack drove me through the north end of Mobile, Alabama, past several chemical factories. We went down a highway hedged by tall yellow grass and slowed down in front of a power plant, where dark smoke was chuffing out of the highest tower. Womack parked beside a creek; the air as we stepped out smelled faintly noxious.

“This is called Hog Bayou,” he said with a sweep of his arm. He was wearing a Nike T-shirt and wraparound sunglasses. In the 19th century, the area was a dense forest, and the former slaves who lived there gave it that name, Womack said. “You could walk right across the street and kill a deer, kill a hog, catch some fish, and bring them back. You’d have food for a week.” Womack, I’d been told, was the best possible guide for a tour of the waterfront; his family has lived in the area for more than a century, and at age 67, he’s become both a shrewd activist and a repository of neighborhood history. “So according to folklore, this is where the African slave taught the American slave how to live. The Africans hadn’t been slaves for long, and they knew more about being free than being slaves.”

By “the Africans,” he meant the last known group of people brought here to be slaves, in 1860 from modern-day Benin. The slave trade had been illegal by then for half a century, but a Mobile businessman reportedly sponsored a voyage to Africa on a bet that he couldn’t pull it off without being caught. [Read an excerpt from Barracoon, Zora Neale Hurston’s 1928 interview with the last living survivor here.] When the Africans were freed, just five years later, they still spoke minimal English and were far less acclimated to American society than native-born slaves. So they took refuge in this area north of town, which was marshy at the time, separated from the Mobile city limits by a swamp. They established an independent society — “the first continuously controlled by blacks, the only one run by Africans,” as the scholar Sylviane Diouf puts it in her 2007 book Dreams of Africa in Alabama — and shared their belongings, built one another’s homes, and governed according to tribal law. Many of their descendants still live there.

Womack and I walked up a short concrete ramp, along the creek bank, to get a better look downstream. I was startled by the view: In the middle of the placid river, there was a lush headland of pine trees and tall grass. “Yeah, this is the bayou,” he said, noticing my reaction. “For a long time International Paper didn’t let people come back here. After it opened, we brought some 85-year-old women over in a bus. They said they never knew this was here, been over here all their lives, they just busted up and started crying.”

The desolation of Hog Bayou is similar to what’s happened to Africatown as a whole, even though it’s as much a part of American history as Gettysburg or Appomattox. “This is the only place where somebody can say, ‘I know where my ancestors came from,’” said Donna Mitchell, who was executive assistant to Mobile’s first black mayor and is now spearheading economic-development efforts in the neighborhood. “Questlove” — percussionist for the Roots, and a descendant of one of the Africans brought over in 1860 — “can say, ‘I came from there.’”

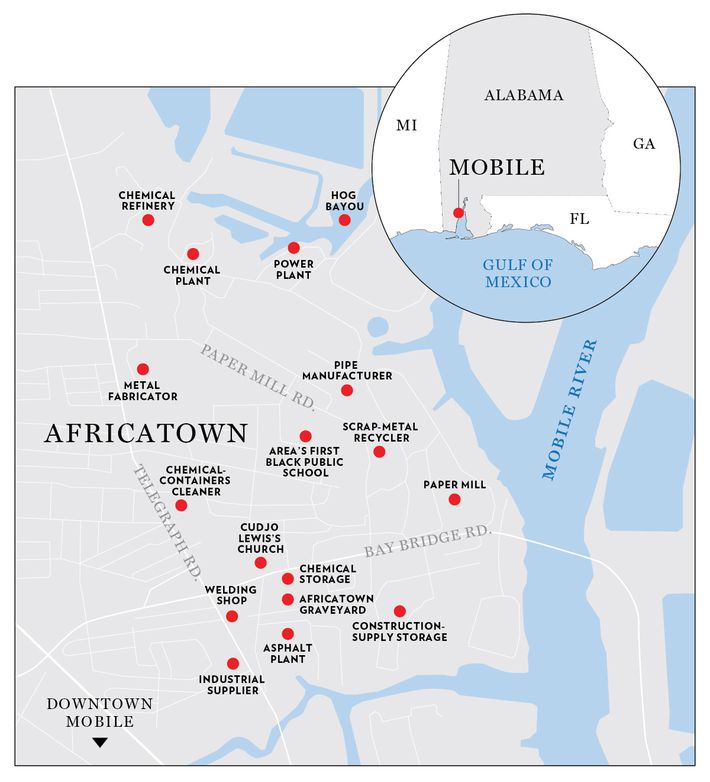

But instead of getting its due, Africatown’s business district was bulldozed in the 1980s to make room for a road connecting two highways, much of its housing stock is falling apart, and residents believe pollution from the factories that surround the community has created a cancer epidemic. It could well be vacant within another generation, in which case it will likely devolve into an industrial wasteland. “This could be an extremely good story for the state, or it could be a horror story,” Mitchell said.

However, a new chapter to this saga began in January, one that local leaders like Womack and Mitchell hope will rally the neighborhood and bring in grant money and tourism. During low tide, a reporter for the local newspaper — Ben Raines, son of the former New York Times editor Howell Raines — found what appeared to be the remains of the Clotilda, the ship sent to Africa by the Mobile businessman, Timothy Meaher. In 1860, he had the ship burned, to destroy the evidence, but it didn’t turn completely to ash. Archaeologists determined in March that the ship Raines found wasn’t the right one; it was too large, they said, and its wood wasn’t charred. But they said a more serious effort to find the Clotilda might be on the horizon. Representatives of the Smithsonian and the National Park Service have been on-site to help.

When the Africans regained their freedom, in 1865, most were between the ages of 15 and 30. At first they were bent on returning to Africa, but their former owners refused to help, so many couldn’t pinpoint their villages on the map, and no one knew how to arrange the voyage. In the meantime they camped out on a peninsula north of town. “The Africans, methodically, explored every inch of the area, noting the animals, the plants, and the trees that could help them survive,” Diouf writes.

Eventually they settled into jobs, some of them working at lumber mills owned by Timothy and James Meaher, the brothers who formerly enslaved them. They saved up enough to buy land — some of it, again, from the Meahers — and apportioned it among themselves. They decided to “makee de Affica where dey fetch us,” as Cudjo Lewis, the last survivor, later put it. African-Americans from other parts of the South heard about the settlement and moved there to join.

However, the Meaher family still owned most of the property between the village and the waterfront, and the Africans had no voice in how it would be used. The first factory, International Paper, located there in 1929. More followed, and by the 1970s they encircled the neighborhood. At first, the residents didn’t necessarily mind, because the plants brought thousands of jobs. “They said, as long as you live in the community, we’ll hire you,” Womack said. “As long as you can walk and breathe.” For a while, the neighborhood thrived. The Africatown Elks Lodge was packed at the end of every shift. There were grocery stores, barber shops, a motel, and a movie theater, all within walking distance.

Even then, there were signs something was wrong. Not only was International Paper’s mill one of the largest in the country, but the company also had its chemical refinery next door. Some days a putrid smell filled the neighborhood. “Like we standing out here now, you couldn’t stand out here,” a 62-year-old resident, Charlie Walker, told me in the front yard of his church, Yorktown Missionary Baptist. “Man, it smelled like a dead …” he drew last the word out while he settled on the right noun: “Horse!” He shook his head. “It would upset your stomach.” Other days, residents told me, ash would rain down from the sky. They learned not to hang their clothes out to dry, and they noticed new cars would rust within a few years. Their roofs needed repairs all the time. But for a long time no one seriously worried. “My mom used to work out there, and she’d say, ‘It smells like money,’” Donna Mitchell said.

In 1992, Scott Paper Co. released into the air 630,000 pounds of chloroform, a chemical known to cause cancer, according to a report in the Birmingham News. International emitted another 56,000 pounds, but it had released four times as much in 1989, before an EPA crackdown. The Associated Press reported that by the late ’90s, the EPA had discovered the air in a nearby town contained dangerous levels of nearly a dozen pollutants — and this was three miles from the factories, whereas Africatown is circumscribed by them.

Nearly everyone I met ticked off a list of family members who’d been felled by cancer. “My brother died from cancer — lung cancer, tumors on his brain,” said Pat Dock, another lifelong resident. “My husband died from cancer. I mean, when you live in a place, there ain’t nowhere else to go. And you’re inhaling this day in, day out.” Walker said his parents, his two sisters, and his brother died from cancer, and his other brother has cancer now. Christopher Williams, the pastor at Yorktown, said he sometimes officiates over two or three funerals a week, most of them cancer-related, sometimes for parishioners in their 40s and 50s.

There are no hard statistics available — proving cancer clusters takes complicated epidemiological study — but Williams said he sent a questionnaire, some years ago, to the roughly 150 members of his church, and about 100 responded that they or a family member had had cancer. “They expect it,” Williams said. “Everybody’s going to get cancer out here. You just don’t know who’s next.”

As if the pollution weren’t enough, when the construction of the new road began on top of the abolished commercial district — all that’s left is the Elks Lodge — bones were turned up. City authorities assured residents that though the road ran right by a cemetery, they’d only found dog bones, Womack said. But he doesn’t believe it: “We think they were more than dog bones.”

Two of the three paper plants, International Paper and Scott Paper, wound down their operations in the 1990s and closed by 2000. Other industrial businesses have taken their place, but between the loss of the paper-mill jobs and the dismal state of the infrastructure and housing, Africatown emptied out. Womack said the population once numbered about 15,000; now it’s fallen below 2,000.

The more pessimistic remaining residents feel like they’re under siege. Being inside the neighborhood, it’s easy to understand why. Only three roads lead there from Mobile, and anytime I visited, I had to drive through a haze of dust or smoke. Trucks constantly rumble down the few main thoroughfares. On the residential streets, there are dozens of abandoned houses, with their fences bending with rust, Spanish moss dangling from their gutters, and vines winding across their windowpanes, as though the forest is retaking it all.

Earlier this year, after Donna Mitchell went back to her old job, as a nurse, she said she struggled to find energy to keep up her neighborhood projects. “I’d be working like three to 11, or 11 to seven, and I’d get home, and I’d be so tired.” But then she’d imagine one of the Clotilda passengers, a young woman named Zuma, jabbing her in the ribs. “She’d be like, ‘Get up! Get up! Get up, girl, and tell my story!’ And that’s what motivated me. I had to tell her story.”

Mitchell has already made progress. Under her leadership, the Africatown Community Development Corporation is working with the city to buy abandoned properties, with the long-term goal of building new houses and luring families back to the area. She helped broker an irrigation system for the four-acre community garden, where people from the neighborhood can lease parcels for free, and to fund it she organizes a 5K run/walk every summer, in commemoration of the Clotilda. “I was going to change it to September,” she said, “but then the newspaper guy said, ‘Yeah, it’s hot, but imagine that Middle Passage. Running up that bridge in the heat ain’t nothing compared to that.” She recently received a $50,000 grant from the state to create a farmers market.

This spring, too, a $3.6 million grant came in for her group’s most ambitious project, an Africatown welcome center and museum. When it looked like the remains of the Clotilda had been found in January, her first reaction was panic, because she already had plans drawn up for a full-scale replica. “When they found it, that ship was like twice as large. We were like, Oh, hell no.”

While Mitchell runs the neighborhood’s offense, Womack’s group handles defense. Several years ago it beat back a plan to let an energy company install as many as 50 oil-storage tanks around Hog Bayou, and in the process the city agreed to change its public-notice rules, so residents would have more say in these decisions. At one hearing 150 people came to protest. “I won’t say that the fight is over,” Womack said, “’cause the fight is never over,” but he sees it as a turning point. Since then, the mayor’s office has created a neighborhood plan, based on discussions with the residents, that lays out goals of building more houses, seeding new businesses, and adding more urban farms.

Meanwhile Christopher Williams, the pastor, has recruited an Alabama law firm to sue several companies for the pollution, particularly International Paper, which for years had the largest local footprint. The suit, filed last year on behalf of some 250 residents, accuses the companies of releasing toxins in excess of EPA limits. When I was in town, legal staff were interviewing residents, at the church, about their families’ experiences with cancer, to consider adding them as plaintiffs. Donald Stewart, the lead attorney, said he expects as many as 900 after the vetting is done. “They put the nastiest stuff around the people least able to protest it,” he said. “You would think that in 2018,” a century and a half after the Civil War, “we’ve gotten some distance away, but you wonder sometimes.” Williams hopes to force International Paper to set up a free clinic for the cancer victims. Asked for a response, a company spokesman said that “neither plaintiffs nor their lawyers have produced any evidence” to support their claims.

There are tensions between the neighborhood advocates. Donna Mitchell’s strategy depends on support from the factories — for instance, they co-sponsor the Clotilda 5K, and a power company has leased the land for the community garden — and she becomes defensive when the subject of pollution comes up. There’s no scientific data to prove it’s hurt anyone, she said. “It’s kind of like, ‘As long as I can scream, and I never have to prove it, I’ll continue to scream it.’” Womack said no one has been able to afford a comprehensive soil test so far, which costs at least $20,000. He hopes to see a proper test in the course of the lawsuit.

But if the air and soil are so deeply polluted, is the neighborhood already ruined? Ramsey Sprague, an environmental advocate who often works with Womack, says it’s not. Chemical refineries cause less permanent damage than oil refineries, and if the cancer link is confirmed, federal grant money could be available for cleanup projects. “The amount of resources the community could go after are massive,” Sprague said.

The Meahers, still one of the area’s most powerful families, now have a state park, across the bay from Mobile, named in their honor. One descendant is a Mobile attorney; another runs a timber and land-management company; and they own large chunks of Africatown through a real-estate company. They have never made any public statement about their ancestor’s crime, and have “strenuously refused” to release his personal papers, according to Sylviane Diouf. They did not respond to my interview requests.

So finding the old ship, Womack imagines, could alleviate several problems at once. “To me it would mean closure,” he said. “They’ve never admitted they actually did anything, but we know the people came over! We know they were here! Once that closure happens, it might bring this city closer together. It would be something people want to see worldwide. And we could get these old houses fixed up, because we got a lot of old houses in Africatown.”