California’s primary, which culminates with in-person voting on Tuesday, will have a deep influence on the overall story of the 2018 midterm elections. Most significantly, it will shape Democratic challenges in as many as nine Republican-held U.S. House seats that could be vulnerable to being flipped in a blue “wave” election. Those seats represent a large and key chunk of the 23 net seats Democrats need to win back control of the chamber.

Whether those red seats in California ultimately turn blue in November could be heavily affected by the new “top two” voting system that the state has adopted. Under these rules a general election is a face-off between the pair of candidates that get the most votes in a primary, regardless of party. So rather than the traditional Republican-versus-Democrat ballot choice in November, there will be a lot of intra-party duels, where the other opposition has already been knocked out of contention. The system has added an entirely new level of strategy to the primaries at a party level too — especially in terms of avoiding getting locked out of the general election in an otherwise winnable race. But that very prospect hangs over the Democrats in three U.S. House races in Southern California, with potentially huge implications for control of that institution (and the direction of American politics for the next two years).

The same thing — i.e., getting locked out — could happen to Republicans in the two big statewide races for the U.S. Senate and governor, with the side effect that not having any Republicans at the top of the ballot would likely drive down GOP turnout in November. The primary will also serve as a test of Democratic voter enthusiasm and GOP counter-mobilization on the nation’s largest battlefield.

Which is all to say, that there is a lot going on in these races. Here are the key ones:

U.S. Senate

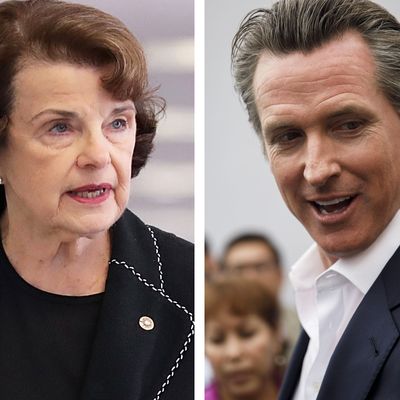

Democratic U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein has been in office since 1992 (she was mayor of San Francisco for a decade before that), and if reelected, would turn 90 during her next Senate term. Her age and a general perception that her centrist politics are out of date in a state and a Democratic Party that are moving to the left have made her vulnerable this year, at least on paper. There are 31 candidates on the top-two ballot challenging Feinstein, but none of the Republicans are well-known and just one Democrat has any significant statewide visibility: Kevin de León of Los Angeles, the Democratic leader in the state senate.

De León has staked out a position distinctly to Feinstein’s left, championing single-payer health care (he managed to get a bill through the state senate) and harvesting endorsements from the California Labor Federation, Democracy for America, and several branches of the Sandernista Our Revolution organization. More importantly, his supporters blocked an expected endorsement of Feinstein at the state Democratic convention and came closer than the incumbent to the 60 percent of delegates required to get the nod.

Feinstein’s huge financial advantage, and the generally accepted premise that the primary is just a trial heat for a fight between Feinstein and de León that will continue until November, has kept this race relatively quiet, with every poll showing the incumbent far ahead. There is some risk that by keeping his powder dry de León could slip right out of the top two; a Gravis poll in May showed him running fourth behind two little-known Republicans, and a more recent SUSA poll had him narrowly leading one of the GOP candidates. That would be a shocker, and not only a blow to progressives opposing Feinstein, but a big boost to Republicans expecting to be “locked out” of the general election for senator, as they were in 2016.

Governor

The race to select a successor to term-limited governor Jerry Brown (who is finishing up his second eight-year stint as governor) has been complicated and dynamic. The presumed front-runner from the beginning has been Brown’s heir apparent, two-term Lieutenant Governor (and before that, San Francisco mayor) Gavin Newsom. Reflecting the Zeitgeist, and somewhat modifying his past persona as someone combining cultural liberalism with a more moderate stance on other issues, Newsom has pointed his gubernatorial campaign to the left side of the road, and has been rewarded with solid labor and progressive support. He is facing three credible Democratic challengers, but the main threat to Newsom for most of the campaign has been former Los Angeles mayor Antonio Villaraigosa.

A long and bitter battle with teachers’ unions over his education policies as mayor (especially with respect to his support for widespread use of charter schools) cost Villaraigosa any real chance at labor support, despite his own background as a union organizer. Partially as a result, his gubernatorial campaign is being heavily financed by a national network of billionaires (including former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg) who are deeply invested in the charter school cause.

Even as backers of Newsom (who supports a cap on new charters for the time being) and Villaraigosa conduct their proxy war over education policy, Republicans are beginning to consolidate support behind a candidate who could well finish second and make the general election: wealthy businessman and partial-self-funder John Cox. Originally, Cox and state legislator Travis Allen — a fiery Southern California conservative and an outspoken fan of Donald Trump — were locked in a fight that seemed likely to keep both out of the top two. The state GOP failed to choose between them in its state convention (where 60 percent of delegates were needed for an endorsement) in early May, though ads run by Cox were beginning to give him some distance over Allen in polls. Then the president tweeted an endorsement of Cox on May 18, undercutting Allen, and the most recent polls have shown Trump’s new favorite running ahead of Villaraigosa for the general election spot.

Cox is also benefiting from crafty ads being run by Newsom “attacking” him in ways that make the target more attractive to Republican voters. And on top of everything else, a third Democrat who has just enough money for serious ads down the stretch, state treasurer John Chiang, is going after Villaraigosa’s vote. Turnout patterns could determine whether Villaraigosa can still make the top two.

It is important to understand that for Republicans the prize for making the top two in either the Senate or the gubernatorial race is simply to avoid a problem: They won’t lose the motivation to vote that having no one on the general election ballot could create. No one really thinks a GOP candidate has a chance to win either office in November. They lost every single statewide race in the national Republican landslide years of 2010 and 2014. The Democratic-leaning 2018 cycle, which in important respects is a referendum on the presidency of Donald Trump (who performed more poorly in California in 2016 than any GOP presidential nominee in over a century), hardly seems the time for a GOP comeback.

But at the margins, statewide Republican turnout could affect the critically important House races.

U.S. House races

There are seven House districts in California held by Republicans that Hillary Clinton won in 2016, and those form the heart of the battleground for Democrats this year. Only one (the 21st District in the Fresno area of the Central Valley) involves a guaranteed one-on-one race, with Democrat T.J. Cox taking on incumbent David Valadao in a district Hillary Clinton carried by 15 points. Cook Political Report rates the race as “Lean Republican.”

Another Central Valley district, the Tenth, was carried by four points by Clinton and only three points by the GOP incumbent, Jeff Denham. Beekeeper Michael Eggman is making his third race against Denham, but has strong opposition from venture capitalist Josh Harder and Riverbank mayor Virginia Madueño. Denham is one of the leaders of a discharge petition drive aimed at forcing a House vote on legislation to protect Dreamers. The population of his district is 40 percent Latino.

Just north of Los Angeles is the 25th District, which Clinton carried by seven points; it’s a toss-up district represented by two-term incumbent Steve Knight, who barely defeated Democrat Bryan Caforio in 2016. Caforio is back for another try, and has labor and progressive backing, but nonprofit advocate Katie Hall is being backed by EMILY’s List and Planned Parenthood. Both Democrats are well funded.

In Orange County’s 45th District, which Clinton won by five points, incumbent Mimi Walters, whose voting record has followed the party line closely, will win one of the general election spots, but a large Democratic field is battling over the other one. Law professor Dave Min, a moderate by California standards (he doesn’t flatly support single-payer health care), was endorsed by the state party, but his UC–Irvine Law School colleague Katie Porter, supported by Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris, has run a strong campaign as well.

Then there are the three Southern California districts where the top two lockouts for Democrats could happen:

In Orange County’s open 39th District (where Ed Royce is retiring), either party could actually be locked out of the general election. Among Republicans, former state legislators Young Kim and Bob Huff were running first and third in a rare public poll taken back in March; Orange County supervisor Shawn Nelson is also running a credible campaign. On the Democratic side there are two heavily self-funding candidates who could break through or knock each other out: DCCC-backed Gil Cisneros, a former lottery winner, who was running second in the March poll, and progressive insurance executive Andy Thorburn, who was running fourth. Almost anything could happen in the 39th.

The open 49th District (which includes parts of Orange and San Diego Counties, and is represented by another lame duck, Darrell Issa) has an equally wild two-party free-for-all. A late-May SUSA poll of the district showed one Republican, former state legislator Diane Harkey, who was endorsed by Issa, running ahead of the field, with five other candidates — including Democratic self-funders Paul Kerr and Sara Jacobs and 2016 Democratic candidate Doug Applegate — within striking distance.

And finally, in Orange County’s 48th District, fears of a Democratic lockout are real but may be fading. Incumbent GOP congressman Dana Rohrabacher is indeed vulnerable (over an array of issues, including his conspicuous affection for Vladimir Putin), but the odds of fellow-Republican Scott Baugh finishing second don’t seem so strong. The Democrat likely to finish second, though, remains unclear: the national party signaled its support early on for stem cell scientist Hans Keirstead, but then switched to real-estate investor Harley Rouda when sexual-harassment allegations arose involving Kieirstead (who claims they are bogus). The state party can’t take back its endorsement of Keirstead, so his name is on influential mailers; it’s unclear what will happen.

And to a large extent, that’s true of this entire primary, where the results may be very slow to take shape. Experts say that by this weekend, no more than 70 percent of the vote may have been counted. So for those of you on the East Coast, don’t stay up too late for returns from California on the evening of June 5.

Turnout is going to be a key variable. Primaries in California, as in every other state, draw a lot fewer participants than general elections, and midterms draw fewer voters than presidential elections, as I noted recently:

In 2016 the general-election turnout was 75 percent of registered voters. In 2014 it was 42 percent, an all-time low for the state. In the 2016 primaries (which included a presidential primary) turnout was 48 percent. In 2014 — the first midterm held under the top-two system — primary turnout dropped to 25 percent, another all-time low.

The top-two system was supposed to boost turnout by attracting independents left cold by the old party primaries, but it hasn’t worked out that way so far. An analysis of mail ballots returned for the primary so far (mail ballots will ultimately form a sizable majority of votes cast) shows the percentage collected from independents running well behind their percentage of registered voters. And overall, it seems California Republicans typically do better in primaries than in general elections in getting their vote out — especially in non-presidential years.

So extrapolations from the primary results to November will be perilous, except in those cases when the first-place finisher achieves a landslide (the top two proceed to a rematch even if the No. 2 finisher’s totals are minuscule). But June 5 will most definitely reset the nation’s largest and most complicated battlefield.