Walking around the city, one often encounters architectural anomalies: a glassy, undulating Gehry, say, or an alley of colorful Greek Revivals. But there are certain outliers that are so jarring, looking as if they’ve been plopped down from outer space or transported from rural Nebraska, they make you stop and wonder how they got there in the first place. In some cases, it’s because the owners refused to sell a centuries-old building to developers; in others, it’s because they spent years finagling a wacky façade past the Landmarks Preservation Commission — just a few months ago, in fact, a subdued Tribeca townhouse debuted a twisty, flamelike new exterior. Sometimes, though, it’s more simple: The owners just decided they wanted to paint their Upper West Side brownstone a startling azure.

Tiny Amid Huge

349 W. 86th St., Upper West Side (pictured above)

Built in 1900, this Beaux-Arts-style mansion was nearly made into office space in the ’90s. Neighbors stepped in to save it; the building was last on the market for $50 million.

19 W. 46th St., Times Square

This 12 ½-foot-wide boardinghouse was built in 1865. By 1915, the block was almost completely commercial, but No. 19 survived. Now two women rent the top floor.

124 E. 19th St., Gramercy

An 1880s-era Flemish-inspired carriage house — a former occupant is Winston Churchill’s great-grandson — is nestled up to a 22-unit apartment building.

The Trouble With Being So Small

“There’s a high chance of possible damage from neighboring construction. Digging deeper foundations for taller construction can undermine the foundation walls of the smaller home — and there’s always the risk of big, heavy things falling onto roofs that are suddenly 60 feet lower than their neighbors. And, of course, if a big building pops up next door, you might end up losing some light.” —Simeon Bankoff, executive director of the Historic Districts Council, the citywide advocate for New York’s historic neighborhoods.

Country Farmhouses

121 Charles St., West Village

In 1967, this farmhouse — believed to have been the studio of Goodnight Moon writer Margaret Wise Brown — was transplanted from the UES to a backyard in the Village.

37 Garfield Pl., Park Slope

A 1901 shingled single-family home built in the neo-Tudor style — made clear by its peaked roof, single roof window, and clapboard siding.

203 E. 29th St., Kips Bay

The first floor of this wooden four-story house — which was likely built in the late 1700s or early 1800s — is brick, giving the impression that the rest is floating.

How Do You Take Care of a Wooden House?

“New York began to ban them in the 19th century, but the city is still filled with ones that were built before the law came into effect. Wood is less durable than stone, so it requires more maintenance. In the 1950s and ’60s, vinyl salesmen would walk up and down the streets in Brooklyn and people would buy that instead of repainting or getting wood siding. For repairs, my colleague, preservation architect Dan Allen recommends Burda, a construction company in Brooklyn that’s very familiar with wooden houses. As far as fireproofing: There’s no guaranteed way to fully fireproof a wooden building, but installing flame-retardant insulation and sprinkler systems is a way to diminish flammability. Upgrading electrical systems to modern code is also a very good idea.” —Bankoff

Time-Warped Townhouses

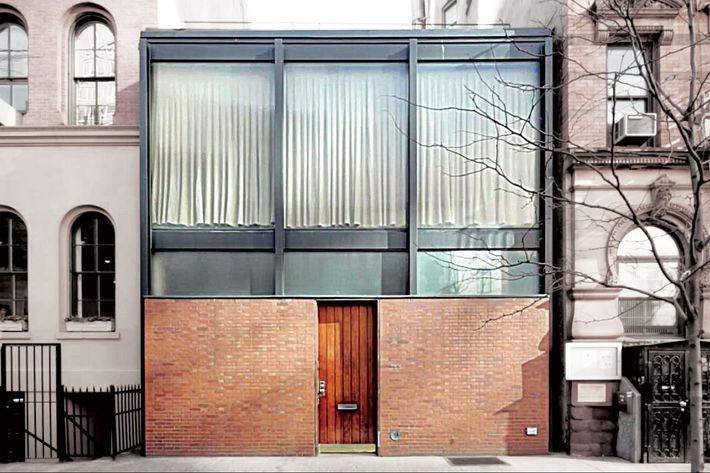

242 E. 52nd St., Midtown

From its brick-and-glass façade to its wooden front door, this 1948 Philip Johnson house (commissioned by John D. Rockefeller III’s wife) hasn’t changed much.

187 Franklin St., Tribeca

Curbed referred to this building, which was designed for a family of four by SystemArchitects, as “the Ed Hardy T-shirt of Tribeca townhouses.”

443 Bergen St., Park Slope

Jeffrey McMahon created this façade with solar panels, Passive House windows, and Hurricane Sandy–reclaimed wood.

How Strict Is the Landmarks Preservation Commission When It Comes to Kooky Façades?

“It really depends on which Landmarks chair you get. If you want to build a modernist façade of your own and you’re in a historic district, you’ll have to present your plan to the Landmarks Preservation Commission. What the chair is looking for is a ‘level of appropriateness.’ That basically means that what’s being built should be complementary in style, scale, and materials. There’s a lot of leeway there. A talented designer can do a lot with that. Things are rarely turned down outright. For instance, the Hearst Tower — which is a giant, weird, geometric thing — is built on top of a landmarked building. The commission allowed that to go through.” —Bankoff

Two Uptown Blues

137 W. 78th St., Upper West Side

This Queen Anne–style rowhouse was likely brightened up prior to the formation of the Central Park West Historic District, which frowns upon painted brick.

106 E. 101st St., Upper East Side

A quarter-century ago, a state agency painted several brownstones on East 101st Street between Park and Lex, where a handful of bright buildings still remain.

If You Want to Go Blue (or Pink)

“No historic district, no problem. But if you are in one, you need the commission’s approval. The owner of the Garfield Pink House, for example, which was painted before the Park Slope Historic District was designated, could only touch it up with the same pink.” —Bankoff

… And a Pagoda in Flatbush

131 Buckingham Rd., Flatbush

There was a long-standing belief that this 1903 Japanese house was built by the foreign consulate. It was not. It was actually designed by Petit & Green, the same firm that imagined Coney Island’s Dreamland. The architects worked with Japanese advisers to ensure stylistic authenticity.

Live in a Modernist Misfit

211 E. 48th St., Midtown

This stucco-and-glass house — on an otherwise unassuming stretch of 48th Street — was designed by Swiss architect William Lescaze in 1934, when the street consisted exclusively of pre–Civil War houses. It was landmarked in 1976 and is considered the first modernist home in New York City. The building was also the first residence in New York to have central air-conditioning. Updates in recent years have included a glass-enclosed hydraulic elevator, a Boffi kitchen, new structural steel inside and out, and a north-facing courtyard with solid-glass-block skylights. It’s going for $4.95 million.

This article has been updated to clarify that Jeffrey McMahon designed the eco-friendly condo at 443 Bergen St.

*This article appears in the July 23, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!