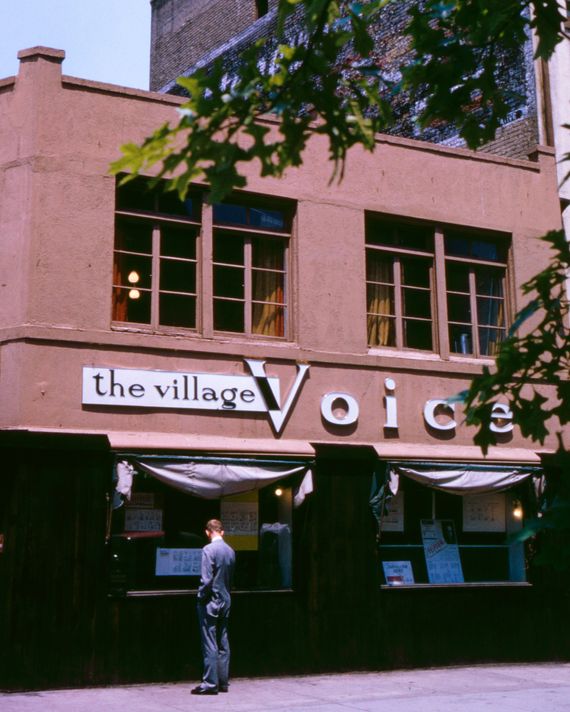

The Village Voice, closed down yesterday after 63 years in business, was where I learned to write. It took me awhile, because I was uncomfortable with the “I” word. The Voice, of course, was full of “I,” but I’d spent two years as a fact-checker at Newsweek where it was a no-no, and the habit was hard for me to break.

I’d left Newsweek in 1964 to volunteer in the civil-rights movement in Mississippi, first in Meridian — I arrived shortly after the activists Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney were declared missing, but before their bodies were found. After Meridian I moved to Jackson, where I was assigned to do publicity for a very dispirited movement. While I was in there, in 1965, I heard about something called the cotton-allotment elections. I couldn’t get a real reporter to write about the cotton-allotment elections, so I took a trip to the Delta and wrote the story myself. My good friend Jack Newfield was at the Voice by then. I mailed the story to Newfield, he showed it to Dan Wolf, the editor-in-chief. Dan published it.

I returned to New York late in 1965, dead broke, and bunked with friends who happened to live near the Voice’s office on Sheridan Square. Newfield mentioned me to Dan Wolf again, and Dan said “Tell her to come in and see me. She sounds like an interesting person.” So I went to see Dan. He was, as usual, smoking his pipe. On the spot he offered me a deal: He’d print anything I wrote that he liked for $75 a shot. The Voice was heavy on columnists, he told me. What he needed was general news reporting. Could I handle that? I said yes. The unemployment-insurance people put me in a category called “Partially Employed.”

Seventy-five dollars wasn’t going to get me my own apartment, but I was like a genie that had been let out of a bottle. My friends gave me leads to under-the-radar stories that, in our opinion, were newsworthy. By that I mean a news story that was unlikely to appear in the New York Times. I wrote about a police informer who had infiltrated New York CORE. I trekked out to a theater in Brooklyn to report on a soul singer then unknown to the white world whose name was James Brown. (On the subway ride home, I met Diane Arbus. She’d gone to the concert to photograph Brown for the early incarnation of Clay Felker’s New York Magazine. Her daughter, Doon, was going to write the captions. Felker had Diane’s photos but my print story came out first, and he did not enjoy being semi-scooped by the Voice.) I pulled all-nighters and staggered into the Voice the following morning with my not-so-neatly typed copy. If Dan wasn’t around, I gave my copy to Diane Fisher, who worked in a cubbyhole and seemed to be the paper’s managing editor.

I turned in a story nearly every week. Dan seldom did any editing. As Newfield used to say, Dan’s job was to orchestrate his writers’ obsessions; he didn’t like ‘professional’ writers. I have to admit that my first pieces for the Voice were awfully stilted, but eventually I improved — and I got comfortable with the “I” word, like everyone else at The Village Voice.

Dan would hold court in his Sheridan Square office after the paper went to bed, but I seldom went to these weekly sessions. Even though I could be an aggressive reporter, I was shy when it came to socializing, and anyway the Voice was never one big happy family. Staffers groused about one another and venomously guarded what they believed was their turf. Joe Flaherty was the biggest grouser. “I write about real stuff on the Brooklyn docks and “she — meaning me — gets the front page for a fucking story about an abortionist,” he complained over drinks at the Lion’s Head, the bar near the office. Barbara Long, who wrote about sports, had a hissy fit when she saw my James Brown story. For some inexplicable reason she thought he was part of her beat. Nat Hentoff was a wicked complainer. If he didn’t like what you wrote, he’d say so in his column the following week. None of us earned a living wage at the Voice. I guess that explains the grousing. We knew that the paper had suddenly become profitable and we wanted to be paid better.

Dan’s opinion was that the Voice was the best showcase in town for emerging writers, and of course he was right about that. Editors and agents began to write me letters saying “If you think you have a book in you, let me know.” When I felt that I did have a book in me, I got in touch with two of those letter writers, an agent and an editor. It took me four years to finish Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape. It became a best-seller. I became financially stable for the first time in my life. But I kept writing for the Voice, on and off, for another 20 years.