Paul Smith’s central-London studio-cum-den is filled with thousands of art tomes stacked in casually dangerous piles. The walls are studio-hung with photos and framed memorabilia—a Chet Baker Let’s Get Lost T-shirt, a poster for the movie Il Gattopardo, some very fine Marc Quinns, a bespoke matte-black racing bike made to fit its owner’s six-four frame, the occasional plastic fried egg.

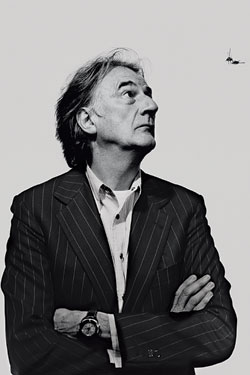

And of course, there’s Smith himself, a gently leonine 61, outfitted as usual in one of his signature mash-ups: unwashed blue-black jeans, custom suit jacket with jaunty floral lining, lime-green socks, and a cowboy-cut shirt made from what he calls “very posh fabric,” fastened with a happy array of mismatched buttons.

It’s comforting that the designer who has been the most successful at getting his notoriously fashion-shy gender to wear color—not play-it-safe pastels but antic, intense, vivid hues—is himself a daily practitioner. Paul Smith has made a fortune and earned a knighthood from his belief that men will wear color, if it is presented with humor and dash; so the chromophobia of his peers puzzles him. “Certainly, if you look at most front rows of most fashion shows, everybody is dressed in black. The bulk of clothes sold in the world are probably black. I presume that’s because black with black with black just works,” he says, then elevates his eyebrows. “I can’t think of anybody else who uses color: Martin Margiela, mostly black; Helmut Lang, black; Jil Sander, black. Prada uses nice pattern.”

Color, in Smith’s conception of it, shows character. “You’re quite artistic, so you wear a little colorful tie,” he explains. “Or, I’m quite quirky and I wear a colorful pair of socks. It’s about using color as punctuation marks, not about wearing an entire lilac suit.” He attributes this affinity to his sixties youth and “the whole San Francisco hippie scene. Men were wearing clothes in a dandy, more feminine way. Floral shirts were very normal.”

Esquire fashion director Nick Sullivan is one of Smith’s converts. “He has a way of making men feel a little bit dandified without feeling foolish,” Sullivan says. “It’s easy to be goofy and make people feel uncomfortable. It’s much harder to be witty.”

“I’m a very down-to-earth person,” says Smith. “And anyone who knew my clothes, knew this. Y’know: If Paul said you can wear a red sweater, it was sort of okay.”

His clothes are informed partly by his art sensibility and partly by necessity. In 1976, when he launched his collection, Smith had a meager fabric selection at his disposal, “normally a blue-and-white stripe or a piece of white fabric. That’s how Paul Smith ‘classics with a twist’ came about,” he says, using his oft-repeated motto to describe his philosophy. “So I started playing—blue buttonholes on a shirt, different color buttons on the cuffs. It was a sort of nudge into color.”

The spring collection, taken as a whole, is not a gentle nudge. It’s a shove into the middle of a chorus line of raspberry and red sweaters, Kelly-green polo shirts, deck shoes in Sunny Delight orange and Pepto pink, that is in part an homage to the optimistic SoCal palette of his friend David Hockney. Smith bumped into the artist one day and was struck by his ensemble: gray chalk-stripe suit, emerald-green shirt, rich-blue tie. “I’d forgotten about David’s style,” Smith says now. “The fact that he’d put a tie with a rugby shirt, and it was just so wrong, he just looked so right.” Only a few will wear the collection undiluted—the members of the young Brit music fraternity, perhaps, like Razorlight and Franz Ferdinand, who rock their Paul Smith with the volume turned up loud. The rest—the ones who’ve bought a suit here, a shirt there, and maybe a coffee mug, those who’ve made Paul Smith Ltd. into a $650 million empire with 400 stores in 35 countries—will do it nudge style.

Smith is not a dandy by birth. He’s from a working-class family in Nottingham. Dyslexic, he left school at 15 and intended to become a professional cyclist, until a serious accident in 1963 left him hospitalized for six months. Soon after Smith recovered, he fell in love with Pauline Denyer, a fashion-school graduate and teacher who fueled her boyfriend’s interest in clothing design and encouraged him to start a boutique. Paul Smith Vêtement Pour Homme opened in 1970; twelve feet square, with a weekly rent of 50 pence (about $4.50 today) and open just two days a week, it sold what were then exotically hard-to-get labels like Kenzo and Katharine Hamnett alongside the sort of whimsical objets trouvés for which he is now known. The shop was not exactly mainstream Nottingham fare, but the duo kept themselves afloat, with Denyer teaching and Smith freelancing as a tailor, stylist, and window dresser. “That shop became quite famous,” says Smith, “because there was no compromise.”

As he learned to sell clothes, Smith also took evening classes to study how to make them. A military man taught him to tailor, imparting the secrets of ceremonial dress (“It’s all about important, elegant, fine posture”). Some of this upstanding aesthetic is evident in his signature cut today—though he firmly believes that the art of fit lies in the eye of the beholder, and he points to designer Thom Browne, with his love-’em-or-loathe-’em “shrunken” silhouettes, as proof of this philosophy. Smith’s menswear business became a thundering success.

Then there’s the elusive women’s business. Smith introduced a women’s line “by demand” in 1993 and, though solid, it didn’t have nearly the impact of his menswear. “There are something like ten or fifteen times as many women’s companies as there are men’s, so it’s a huge competition,” he says. “A lot of it these days is not about the clothes, it’s about the advertising power, the power you have to open shops. It’s a lot more to do with buying into the world that surrounds the label or the designer, which is unfortunately often extraordinarily false.” The glammy brouhaha surrounding women’s fashion (“the image, the girl, the makeup, the shoes”) isn’t particularly his cup of tea. “I don’t have a strong feminine side, which I think is a disadvantage,” he says. Still, he plays to his strengths, concentrating on witty tailoring, shirts, raincoats, and knitwear, while relying on the assistance of womenswear design director Sandra Hill for more feminine pieces. Certainly, Smith gives the impression that he would much prefer to hobnob with people like Eboy—the German collective of digital “pixel artists,” whose work he recently featured on his clothes and accessories—than aggressively pursue cash and cachet in the women’s sector.

Smith laments the decline of the peacock male in the modern world and bemoans the decline of flamboyant youth tribes, from mods to hippies to the crazy-colored British goths, that have kept menswear interesting over the decades. “I love all that because it’s self-expression through nonviolent means, not wanting to look like your elder brother or your mum and dad, just saying, ‘I am me,’ ” he says. In his view, clothing—in fact, just about everything—should be leavened with humor, and the world takes itself too seriously too often. “People grow up so quickly now. In a way, they miss a lot of fun.”