“The only thing that made me weak was seeing the models cry,” Christian Lacroix says.

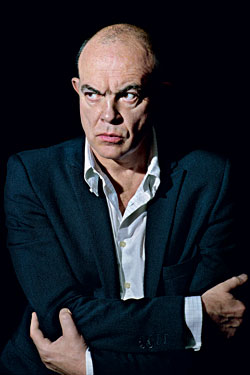

The designer is sitting in the reception room of his Paris atelier not even 24 hours after the haute couture show that could well be his last. Lacroix showed under an order of protection from a French court, in spite of the fact that his American owners have basically pulled the plug. He says he hasn’t been paid in eighteen months, and neither have his suppliers. “People say I am a crazy French,” he says, “that I need this for my ego.” Lacroix talks with his entire face, his whole body, bending and extending and waving and wiggling around. “Non,” he says. “Non. This is not for me.”

The collection is hanging on racks in front of him, and a television is running, on a loop, the basically flawless exposition of 24 looks: Each model an exact representation of traditional chic, this one in a nearly backless evening gown, that one in a strong-shouldered cape. The palette is dark, somber: navy blue and black and gray, with exuberant bursts of color here and there. The models are wearing their hair in dramatic chignons covered by black jersey and cinched with large diamanté brooches. There’s a slight air of mourning about some of them, but they are all impeccably elegant. These are clothes that do not experiment with irony or with whimsy or with the sometimes “modern” idea that to be ugly is to be chic. They announce themselves as fashion; they announce themselves as, above all, French.

What you cannot hear on the video is the applause as each look is paraded through the three salons of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs: There is a diplomatic silence in the press room, and then, like a summer storm moving across a very still lake, comes the muted patter of applause from first the customers and then, softer still, the friends. Nor can you see, on the video, the view outside the museum’s long windows of the Tuileries, where a terrific periwinkle cloud became too heavy for itself and began pelting large, splashy drops on the garden’s sandy paths.

The models take their final turn, with tears running down their pale, pale cheeks, and in the front row, journalists (who are clapping now, and standing up) and clients and friends are crying, too. Behind them, a homemade CHRISTIAN LACROIX FOREVER! banner is held up by the designer’s oldest customer, a statuesque French aristocrat named Pia de Brantes; her white-haired mother and her very tanned daughter have the other side. The sad-accordion soundtrack gives way to a strangled Spanish version of “I Did It My Way,” and then there is Lacroix taking his bow, in a lilac shirt with an open collar and a sharp, dark suit. On his arm is his grand finale, a “bride” dressed as the Andalusian Virgen de Rocío.

“I didn’t cry!” he says proudly, raising his enormous dark eyebrows and pointing at the screen.

“But, oh, look at my big ears!” He lets out a sheepish peal of laughter—his ears, indeed, are huge.

Christian Lacroix has had his own fashion house for 22 years, ever since star turns designing for Hermès and Jean Patou led to backing by Bernard Arnault, the chairman of the most powerful fashion conglomerate in the world, LVMH. It was the ultimate fashion nod. Lacroix had loads of buzz. It seemed like a safe bet.

And, for a minute, it looked as if it would all pay off: Lacroix was like the court designer to the eighties nouvelle société. During his first runway collection, he debuted the skirt that is still his signature: the pouf. It’s a giant meringue of fabric with a hem that turns in on itself. His were made of sumptuous taffetas and silks, and were the perfect symbol for all that was maximal and decadent about that era, and quite an appropriate vehicle for understanding his design ethos. Lacroix does not shy away from heavy brocade; he has no qualm with beadwork or lace or anything resembling medieval tapestry. If you had been invited to, say, Saul Steinberg’s for dinner, you would definitely wear Lacroix; he was a great friend to Princess Di.

The pouf got knocked off all over the place (still does), and Lacroix became such a part of the fashion vernacular that he was a punch line on Absolutely Fabulous (“It’s Lacroix, sweetie!”). WWD famously reserved its largest-possible headline font to declare LACROIX TRIUMPHANT! after one of his shows.

But he never, not even for one year, managed to turn a profit. Certainly LVMH knows how to take critical and popular success and turn it into a lucrative handbag, fragrance, ballet pump—they do it all the time, with Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, Givenchy. But in the case of Lacroix, it never worked. The perfumes crashed—there was one effort called C’est La Vie, released by Dior Parfums, but it faded quickly in the early nineties, and there was another licensing arrangement with Inter Parfums, and another still with Avon, but none was Opium; none was Shalimar.

Lacroix continued to lose money on both his ready-to-wear and haute couture collections, so lower-priced lines called Bazar and Jeans were launched, but Lacroix’s spirit was not well served by T-shirts or denim; what he does really only makes sense when executed opulently. On T-shirts and knits, it all just looked gaudy and sad.

In 22 years at LVMH, Lacroix went through eleven different presidents. But for Christian Lacroix, profit has never been the point. “Businessmen and market people are so far from artists and creative people,” Lacroix says now, regretfully. He is munching on a plate of pastel macarons from Ladurée, while outside there is the whir of military planes rehearsing for Bastille Day on the Champs-Élysées. “Mr. Arnault was the guy with the money. But perhaps the chemistry was not there. It’s this matter of alchemy, of being the same fit, the same rhythm, the same target, and too often it’s a matter of opposition, of war. I think they were very disappointed with me from the beginning because the fragrance was not successful, but it was not my fault. I think it happened when my name was not enough known. And then they signed away licenses without saving creativity. They much prefer to sign with people able to give them back a great amount of money than with people capable of understanding timeless passion. Perhaps LVMH focused only on numbers and bottom lines and was not happy with passions.” He grabs a pale-green macaron—pistachio—and stares into space for a moment. “In the end, you know, Mr. Lacroix had to shut his mouth.”

Four years ago, perhaps sensing the impending larger doom, Arnault gave up. He was involved in a transaction with a South Florida–based company called the Falic Group. The three (unfortunately named) Falic brothers acquired Urban Decay and Hard Candy—teenybopper beauty lines—and later wound up with Christian Lacroix as well, for a price Lacroix dismisses as far too little (the Falics did not return multiple calls for comment). Now the Falic brothers are attempting to sever their relationship, and Lacroix throws up his hands. He’s simultaneously—cue the accordion—philosophical and hopeful and nostalgic.

“Our last meeting was very moving,” he says about Arnault. “We said nothing sentimental, but it was tacit, not spoken, but we both knew. It was a pity.”

There is no equivalent in Italian or American or English culture to the haute couture.

Couture is an over- and misused word—too often, it gets slapped onto things as a catchall phrase meaning “fancy.” But what “haute couture” really means is clothing made entirely by hand, and haute couture refers only to the small group of designers who are members of a French trade group called the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture Parisienne, which was founded in 1868. There are strict rules for membership in the Chambre Syndicale, regulating the number of original designs produced each year, as well as the number of trained specialists who work on those collections. These specialists declare their profession at 16 and take a specialized professional baccalaureate exam, followed by years of apprenticeship. Many of the members of the Chambre Syndicale have large, multinational companies backing them, absorbing the financial burden. Chanel, Givenchy, Valentino all still show haute couture, because to have such a division is still considered important for branding, like some sort of unbelievably expensive and rarefied biannual ad campaign. Indeed, at the Chanel haute couture show, just hours after Lacroix, the models marched in front of massive plastic renderings of perfume bottles, a grand merci, perhaps, to what makes it all possible. Standing on the set after the show, Karl Lagerfeld clasped his gloved little fingers together when asked about the future of haute couture and said, “When you’ve got $3 billion to lose, you are still rich.”

But there’s more to it than branding. Couture is a part of the French identity, like croissants and small dogs and moss-green chairs in the parks.

“Without couture,” says Lacroix, “no life is possible. Nothing. I remember being a teenager in ’69 and our president, Mr. Pompidou, said in a press conference, ‘The France of Camembert is over!’ He was wrong. Of course we are good for some computers and everything, but forever cheese and couture should be sanctified in this country. In Italy they have a very wonderful way of doing fashion, but it is deluxe ready-to-wear. It is not handmade; it is not the coquette. Everything about couture, it belongs to Paris.”

Lacroix’s atelier is off the Rue Faubourg Saint-Honoré, clustered around a courtyard full of potted orange and palm trees, with awnings over the long French doors. CHRISTIAN LACROIX, says a door to the left, HAUTE COUTURE, says another. One day before Lacroix’s show, the sky is dark and there is also a tall woman with her white hair pulled back into a low chignon—Marie Seznec, Lacroix’s longtime muse. She is wearing an orange shift dress with an olive-green ribbon tied around her waist, an olive-green strand of beads around her neck, and she is sipping from a cup of just-squeezed carrot juice.

Up above are the workrooms: Lacroix’s couture studio employs 25 seamstresses, divided into two divisions: flou and tailleur. Flou is concerned with the draping and the design of things, while tailleurs—tailors—do the very technical sewing, constantly ironing as they go. The rooms are unabashedly feminine: The walls are lined with photographs of newborn babies, birthday parties, graduations. The women themselves are not glamorous—they have the home-rinsed frizzy hair and geometric glasses of the Frenchwomen who live in Le Corbusier–esque buildings on the outskirts of town. They work in almost complete silence and answer questions mostly by holding up their work. One woman is folding a long ribbon of silk into an elaborate pattern of roses, which she stitches onto the hem of a coat; another is building up, layer by layer, a shoulder pad with the elaborate layering of stitches and fabric insulation of an old French technique called picotage. In an all-white room, two seamstresses are already working on a wedding dress due in September, hand-encrusting whisper-thin layers of lace.

Couture clothing is only produced if an order is made. If that happens, the premier of the couture atelier takes 30 measurements of the client’s form and then has a mannequin built in her likeness. While the client is expected to schedule a number of fittings, relative to the complexity of the design, fittings can also be done on this new, true-to-life mannequin. It’s estimated that there are, worldwide, only about 150 customers for couture—the prices begin at about $50,000 for a simple suit. Clients these days come mostly from Asia or the Middle East.

When Christian Lacroix says that he did not do this collection for himself, this is what he’s talking about. “I have my reason to be strong,” he says. “All of them, with this magic in their fingers, they have hours on the Metro back and forth; they might have unemployed husband, or difficult children, they are not on the most beautiful level of the French social scale. But they have this. They have gold in their fingers, and I would like to save them first. Because, you know, this is the heart.”

Why the Falics wanted Lacroix is not entirely clear. Lacroix imagines that the wives Falic became his fans when, earlier this decade, he designed collections for LVMH-owned Pucci. “The wives were very, very, very, very excited,” Lacroix says. “I was doing Pucci, so they were in love because, you know, they are Miami and Florida and all of that.”

There were problems with the Falic Group from the start. According to Lacroix, his new partners began with a long-term view of the company that happily dovetailed with his own: They would cancel the diffusion lines and buy back as many licenses as possible in an effort to shore up Lacroix’s position as a maker of extremely high-end luxury product. He would continue with his biannual ready-to-wear collections, and he would also continue to design haute couture. The brand would have a moment to reposition itself and, ideally, reapproach the licensee market from a newer, more elevated position. This method became popular in the nineties, when Tom Ford did it at Gucci, and then Burberry followed suit. The problem with this strategy is, of course, that it eliminates all of the immediate moneymakers, however modest, in the interest of making even more money later on.

So the Falics shut everything down and decided to open two splashy stores, one in Las Vegas, Nevada, and one in New York. The New York store opened in April 2008 with a giant party at the Gramercy Park Hotel, where Lacroix snuggled between Sarah Jessica Parker and Diane Von Furstenberg at dinner. “The party was perfect,” he recalls. “But the boutique”—overseen by members of the Falic staff—“was a little bit cheap. It was a little bit blah.”

The morning after the opening, Lacroix had breakfast with Simon Falic and was told that, given the financial crisis, the brothers no longer wanted to continue, that they were looking for a buyer for Lacroix.

“I don’t know,” Lacroix sighs. “Maybe all of their money was with Monsieur Madoff.”

The Falics had found a buyer, they said, an elusive Santa Barbara, California, businessman who has a commodities company. “He is like Howard Hughes,” Lacroix says. “He has never appeared. In April, they said that he was poisoned in a Chinese restaurant, so he could not sign. In May, they said that he was stuck in his house, burning in the fires. In June, it was his prostate! I called the French Ministry of Finance and they had never heard of him.” So the Falics, in spite of themselves, remain the owners of the house.

Lacroix himself says that he is owed more than a million euros. The fall ready-to-wear collection received many orders that were never filled because the house is in huge debt to its suppliers (Lacroix estimates these debts at 18 million euros). He has begun his own hunt for backers, with the help of his friend David de Rothschild.

“I could not stand having my workers doing nothing during Fashion Week,” Lacroix says. “In this métier, you have a biological clock in your stomach, and they knew: Couture is coming.”

Against the Falics’ wishes, Lacroix began to sketch. He filed for protection with the French government, which he says agreed that the Falics should pay two more months of salary (through August) and 15,000 euros in fees for the models.

The donations began pouring in. Olivier Saillard, of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs at the Louvre, offered three elegant salons. Inès de la Fressange and Bruno Frisoni, the creative directors of Roger Vivier, sent over boxes of shoes; Odile Gilbert volunteered to do the hair; Stéphane Marais chipped in with makeup. Lacroix gathered his suppliers together in the garden behind his office: “I asked them to forgive me,” he says. “And they said that if we would show, they wanted to give everything.”

Taroni and Gandini, two of the best Italian fabric mills, donated fabrics. “I didn’t want to exaggerate,” he says. “I didn’t want to be rude. But this house, it means something to the métier. It means something to Paris. It is really like some happiness pills.”

Lacroix loves fantasy. Growing up in Arles—the sunflowery Provençal town where Van Gogh went to paint—he spent a great deal of time by himself. He is eleven years older than his only sibling. “I was very fond of books, literature, images, legends, and fairy tales. I was always inventing, always sketching. Very early, I felt it was not possible to share my world. I feel we all have a deep, deep, deep soul which is impossible to share.”

In his twenties, he moved to Paris and was living with a “Maoist aristocrat”—a man—in Les Halles when he met a smoky-voiced woman named Françoise. He was not happy with the Maoist aristocrat—“Everything always had to be a bit dusty”—and when he saw Françoise it was as if his Parisian fantasy had stepped off his sketchbook and into his life: “Elegant legs, black belt, high heels, cashmere, and old fur from her mother, a beautiful brooch. What is that?” Lacroix, who still identifies as bisexual, fell madly in love. “At first sight,” he says. “So we went to the movie theater, and I invited her to a Russian restaurant, an exhibit by Braque. She was perfect.” Françoise divorced her husband, and she and Lacroix have been together ever since. “We remain child together,” he says, “for 35 years.”

The afternoon of the show, Francoise is there, her red hair cut into a severe bob. “C’est la vie, c’est la vie, c’est la vie,” she sighs. “I have been with Christian through the ups and downs, and this one, this will be fine.” All around her, the clients begin filing in. Danielle Steele is here, wearing a white blazer from Balmain with shoulder pads the size of tennis balls. “It’s very worrying,” Steele says, wrinkling her brow. Suzanne Saperstein, the ex-wife of a Texas billionaire, is across the runway, with her pillowy lips and two belts slung over her jeans. Kelly Sia, wife of a Singaporean businessman, is wearing a raspberry-colored strapless dress. “He made my wedding dress,” Sia says, looking sad.

Lacroix, meanwhile, is backstage, bending and writhing and wriggling before a throng of television cameras. He is laughing a lot, but he appears tired, stressed. In his fantasy version of this story, there is, somewhere in the audience, a savior in the crowd who will be dazzled by what he sees today. He will take out his checkbook, the atelier will go on.

The seamstresses arrive en masse and disperse quickly to their dresses, each of which is hanging in a collapsible black wardrobe. A short woman with an Ace bandage on her ankle touches her dress and then crosses herself, kisses her fingers, and closes her eyes.

“I have my conscience with me,” Lacroix says, smiling his great big circus smile. “And something in my soul, in my gut, it is my Jiminy Cricket saying that I will find my way, a wonderful white knight will arrive on a horse, a beautiful princess! I am sure we deserve it. Without being romantic, the workroom deserves to be saved. Without being poetic, this collection is one of the best that we did.” He says it again and again, into tape recorders and microphones, and slowly for people wielding notebooks and pens.

Afterward, Lacroix went to the outskirts of Paris to watch Givenchy. This, combined with the presence of Yves Carcelle, a member of LVMH’s executive committee, at his show, started a flurry of rumors that LVMH would save the day, that Arnault would be too heartbroken by the potential end of the house to let such a thing happen. A day before his show, Lacroix lunched with Jean-Jacques Picart, his original business partner. And in between fittings he got a letter from another friend at LVMH. “This is such a shame,” the note read, “we are with you.” And then, the next day, lunch with Carcelle. “It is like being at my own funeral!” he says, laughing.

The deadline for bids on the company was July 28, and Lacroix’s friend David de Rothschild was helping him approach various European investors. Several offers have been made; there was one from a client whom Lacroix declines to name, saying only, “I prefer to keep her as a customer.” Later it is revealed that her father is president of Uzbekistan. A French turnaround company called Bernard Krief Consultants expressed interest, but that company’s resources were deemed insufficient by the courts. Currently, the Italian Borletti group, which has a stake in the Printemps department store, has an offer pending, which would cut more than half the staff, and the Falics have put forth a restructuring plan that calls for a 90 percent reduction in staff, making the label into a licensing house. The remaining 10 percent would be largely administrative—the workroom would not be saved. In this scenario, the Falics would continue ownership of Lacroix’s name, which they could use in an attempt to recoup their debt.

Right now, Lacroix is in Arles, close to his roots, catching his breath, waiting to hear from the court that is considering the offers—as his company has filed for court protection from its creditors, it is ultimately the courts who will decide its fate.

He is beside the River Rhone, near the grocery owned by his grandparents, near the fields that he walked through to school: They were filled with rubble from World War II then—now they are clear and the avenues are full of tourists from Japan.

His future is uncertain. He does have his own company, XCLX, through which he designs costumes for theater, opera, and ballet—work he describes as incredibly fulfilling but not helpful with bills. He also designs for TGV trains and movie theaters and hotel rooms and luxury condominiums in Dubai, but, of course, that market is shaky right now, too.

Mostly, he hopes he can keep his name. “I will be like Prince!” he says, and laughs sadly. “The designer formerly known as!”