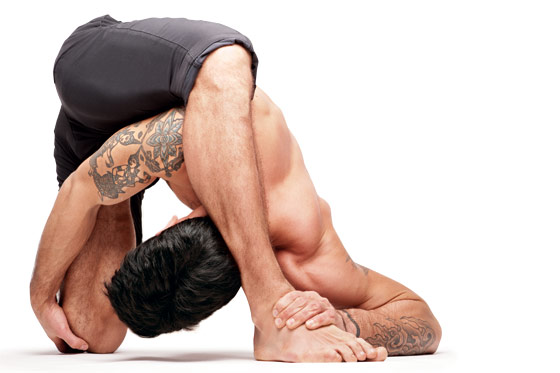

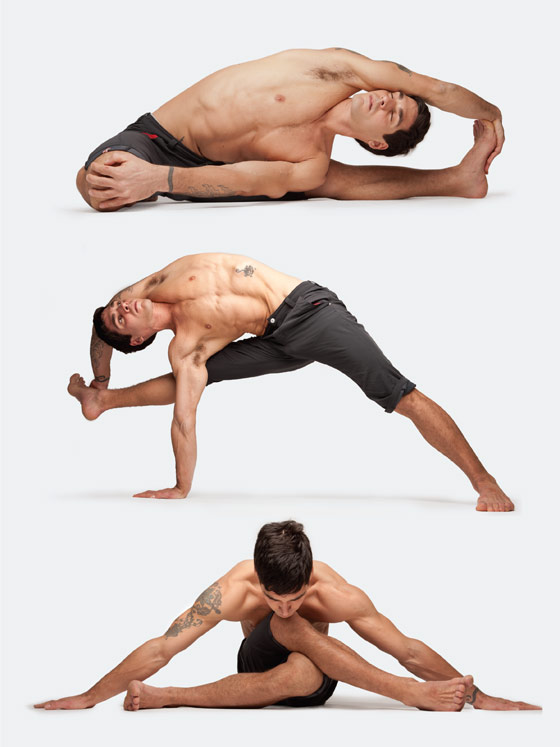

David Regelin draws his dark eyebrows together into an expression of concentrated disdain. The eight students before him are obediently bent over, ankle to thigh, like a flock of Lululemon-clad flamingos, but the instructor does not like what he sees. “A lot of you think you’re good at yoga,” he proclaims. “You’ve worked hard, and you can get into cool-looking postures. But you shouldn’t be coming to yoga class to perform,” he continues, dropping to a squat before a red-faced middle-aged guy and nudging the man’s earthbound foot forward. “You shouldn’t be coming to exercise, or to get muscles like mine,” he adds, pressing his hands onto the floor to flex his tattooed and indeed impressive biceps. “If what you want is to show off, then this class is probably not for you. If what you want is a fitness class, then this class is not for you.”

Hearing a yoga teacher discourage patrons in New York, where studios have become as common and competitive as yellow cabs, is surprising. Hearing such edicts against vanity come from Regelin, a tall, handsome 35-year-old who once listed his “36-pack” abs as an enticement to attend a retreat and appears in shirtless videos of his practice posted on YouTube (“Hot Om Shanti,” reads one comment), is even stranger. Until recently, Regelin was famous at the Kula Yoga Project—whose Tribeca and Williamsburg studios are frequented by twentysomethings with designer handbags and discreet lotus tattoos—for his popular “Multi-Intenso” classes, butt-kicking workouts heavy on the handstands and set to an indie-rock soundtrack. He was an incipient rock star of the yoga world, where famous instructors live lives similar to celebrity D.J.’s, jet-setting between international workshops and sessions with elite clients. But then, this fall, he abandoned Kula for a small studio in Chelsea called Katonah, a pared-down space in which on a recent evening he was teaching a distinctly different style of yoga.

“Modern yoga has become all about distractions,” Regelin tells me after class. We’re sitting at DuMont, a bistro near his apartment in Williamsburg. “The music, people, the setting. Like I’m going to play Björk while people are doing a hip-opener, and say something about letting go of emotions,” he says, affecting a girlish voice. “And everyone’s going to moan. Ahhhhhhhhh.” He exhales dramatically. “You know that? I hate that.” Regelin, who grew up on the Upper West Side and started taking yoga in the East Village in 2001, has, like many people whose jobs consist of lecturing to a captive audience, somewhat monologic tendencies. “I started to look around, and I didn’t like what I was seeing,” he explains. “It felt like functionality and the practicality of yoga was being diminished.” His problem wasn’t Kula, not exactly. It was the overall popularization of the Ashtanga Vinyasa, or “flow,” style of yoga, in which students execute a set of postures—downward dog, plank, upward dog—in rapid succession, often, according to Regelin, incorrectly. “You look around, you see people fumbling, they’re not getting the postures,” he says. “And the classes are so big the teachers aren’t able to help them do them properly.” Or they don’t bother to. “The other day I walked by a woman’s class and she was telling her class”—the voice again—“ ‘Now do your biggest, best wheel ever!’—I mean,” he says, “that’s not an instruction.” He takes a sip of dark beer. “This is where yoga is right now. It’s depressing to me.”

Regelin isn’t a yoga purist. He’s one of a growing number of people suggesting that amateur yogis may be doing more harm to their bodies than good. “Your body is like a Ferrari,” he explains, and this is true for his, though mine is more like an old Saab. “You can’t just drive your Ferrari on any street. You can’t just park it anywhere. If you’re doing squats with one knee the wrong way,” he says, demonstrating in his chair, “you’re going to be walking upstairs one day and that knee’s going to blow out. And usually the people who do the flow classes for a long time break themselves.”

To hear him tell it, New York’s top yogis are harboring secrets that rival Suzanne Somers’s liposuction scandal. “There’s been a lot of famous teachers who have had, you know, hip replacements and knee surgery,” he says knowledgeably. “But they’re not going to put that out there. If you’re the fast-food industry, you don’t say, ‘I’m obese, eat my food.’ ” His salad arrives, and he declines the pepper grinder the waiter proffers. “I don’t believe anything actually comes out of those,” he explains.

Regelin is to all appearances a person of firm convictions, but they can be overturned. “I was a vegetarian for years,” he says after ordering a burger. “I knew how to defend it really well. ‘We have this kind of teeth, animals have these kinds of teeth, blah blah.’ ” But then he was introduced to the work of Joseph Campbell. “He said, ‘Life lives on lives,’ ” he says, and it caused him to change his habits.

His most recent reversal came when Nevine Michaan, a yoga instructor out of Bedford Hills, New York, approached him after taking one of his classes with her daughter. “She said, ‘You have a problem with your back,’” he recalls. “And she touched the right side of my back where I had this like, knot. She said, ‘The left side of your back is much stronger than your right.’ And she was exactly right. I was like, Who are you?”

Among yoga teachers, Michaan is something of a cult figure. “She’s kind of the yoga teacher’s teacher,” says her daughter Danielle, who opened the Chelsea branch of Katonah Yoga this fall, where Michaan, who has been teaching yoga for more than 30 years, frequently leads classes. A metaphor-spouting 57-year-old with long graying hair, Michaan compulsively “reads” the bodies of nearly everyone she meets, including Westchester figures like Chevy Chase and Martha Stewart, assessing the weaknesses in their posture and prodding them into better form. “If you want to teach someone to make an origami cup, the easiest way to do it is to make the cup first,” she explains while cheerily manhandling me into a seated lotus position a few days after I have dinner with Regelin. “You give it to them and tell them to unfold it, and then just have them refold the exact same corners.” She lifts my chin firmly but gently. “There,” she says. “Now you’re perfect.”

In Michaan’s brand of yoga, which combines alignment-based Hatha with Taoist ideas, the good is the enemy of the perfect. According to Michaan’s theory, people are like fold-up tables. If something happens to one of the limbs, the whole thing goes wobbly. Yoga postures can help straighten them out, as long as they’re doing it right. “Learning yoga from Vinyasa is like learning French in a bar,” Michaan says. “Eventually you need to learn how to conjugate a verb and structure a sentence.”

As she talks, Regelin sits next to her, rapt. Michaan changed the way he thought about teaching, he told me back at DuMont. “After going to her classes, I started looking at my students and I was like, I’m not helping these people. I saw how their practices were evolving and I thought, I don’t want to be a part of this anymore.”

He began teaching classes that focused more on alignment and form, rebranding them “Vesica,” after the vesica piscis, the geometric symbol with mystical connotations. He became more vigilant about adjustments and unsparing about his students’ flaws. “I’m never going to praise you,” I heard him say once. “Praise is bullshit.”

In contrast to the dialogue chirped by most yoga instructors (“You don’t need to do everything perfectly,” one at my gym cooed recently, “because the perfection is inside of you”), Regelin’s inter-class patter could sound harsh, even when he tried to temper it. “I’m not trying to be condescending,” I heard him say more than once, sounding exasperated. And “You’re not in trouble.”

“You think I boss people around,” he says. “But I’m helping them.” He’s right. Regelin is all-seeing; in his classes it’s impossible to get away with a lazy dog or a floppy eagle without him bounding over to adjust your posture. You leave feeling not only muscles that you usually ignore, but like you’ve learned something. Which is, of course, the idea. “Yoga is not about enjoying yourself and having a fun experience that you like; it’s about changing yourself,” he says. “And what changes you is usually stuff you don’t like. It’s like if you go on a trip, and it’s like the worst trip of your life, it is usually the one that transforms you the most. If you go on a trip and everything’s paid for and you’re shuttled everywhere, I mean, that’s great, that’s nice. But you don’t want to indulge all the time.”

At Kula, not everyone was onboard with his Tiger Mom approach, and Regelin, unsurprisingly, saw students drifting away from his classes. “Most people are completely self-indulgent people who only search for the gratifying thing,” he says. “As soon as somebody points out something they’re not able to do, they get defensive.”

Schuyler Grant, the founder of Kula, declined to comment on Regelin’s tenure there. “I’m not going to get into a back-and-forth with David,” she said over e-mail. “He can say what he likes.” But Regelin’s popularity with the other teachers at the studio began to suffer, too, as he found himself getting into frequent arguments. “You know, I’d tell them like, ‘If you really had something to say, you wouldn’t be shouting it over music,’ ” he says. “Or, ‘If you really wanted someone to learn a pose, you wouldn’t be putting together ten different poses that don’t relate to one another.’ ”

When the opportunity to leave Kula for Katonah came, he took it. “David is intense,” says Danielle Michaan. “But it’s because he’s so dedicated.”

These days, his classes are smaller. “I don’t have as many students as if I was like, ‘Be yourself!’ ” he says. He doesn’t blame the people who skitter out after the first class, freaked out by his assessment of their form. “It’s confrontational,” he says. “It’s like going into someone’s house and opening a closet and being like, ‘What the fuck, you’ve got a huge mess in here.’ People have a fear generally of being known. Like this. I fear this. Now people are going to see me and be like, ‘There’s that asshole.’ ”