Last Friday, the day that Brazil’s exhaustingly extravagant Carnaval celebrations officially started, scientists here announced that the feared Zika virus had been detected in urine and saliva. They couldn’t be sure if this meant it could be spread through kissing, but the risk was high enough to warrant a recommendation that pregnant women be cautious and to merit further study.

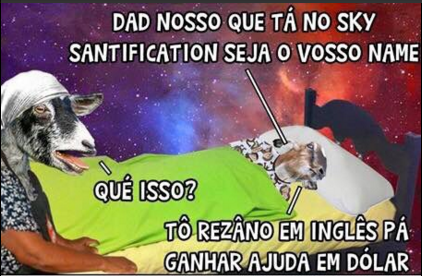

Since Carnaval often involves a lot of kissing — especially of strangers — this was terrible news. But on social networks, suddenly flooded with jokes and memes, the bad mood was undercut by the gleefully dark humor characteristic of the Brazilian web. Users posted pictures of people with condoms over their mouths or entire heads. A teacher posted the title of a fake online photo gallery she had conceived: “See all the celebrities that caught Zika this Carnaval”! A well-liked journalist reminded others that during the festivities streets are worryingly more likely to run with piss than overflow with spontaneous smooches (this is true).

Bad news can be, oddly, good news for the Brazilian internet and its armies of online comedians. There’s something special about internet culture here, more so than the fact that Brazil has one of the world’s most connected and prolific online populations: Brazil’s internet culture is very, maybe particularly, fond of turning national trauma into a source of endless humor and ironic celebration.

There are a couple of local phrases for this phenomenon. Rir para não chorar (“laugh so you don’t cry”), and the supposedly untranslatable A zueira não tem limite, which is something close to “the (aggressive) joking never ends.” And recently Brazil has had a lot to cry about — or avoid crying about.

One of the most famous tragedies to have occurred in the last few years has now become a meme. Actually, it’s become more than a meme — it’s become a part of Brazilian Portuguese and spawned a couple of online holidays. I’m talking, of course, about “7x1,” the score of the Brazilian national team’s catastrophic loss to Germany in the 2014 World Cup.

In the almost two years since, a number of blows to the national psyche — a punishing recession, a shocking corruption scandal, the Zika outbreak — have often incited the response “7x1 was nothing [compared to this].” On both the anniversary of the loss and January 7 (7/1 in the Brazilian transcription), Brazilians superimpose the German flag over their online photos in a twisted reappropriation of the Facebook rainbow or French flag performance.

It’s hard to imagine any other nation celebrating their national humiliation quite so explicitly — or so humorously. (Numbers jokes work well elsewhere, too: When the currency plummeted to 4.20 Brazilian reais to the dollar from a high of 1.5, the obvious response was to declare they’d be smoking their currency.)

The online practice of zueira, when applied to tragedy or failure, is a source of pride for many here, and of consternation for others. Active participants in Brazil’s online life say the phenomenon has deeper roots than just the few tough years Brazil has had recently, or even the internet itself; they cite an especially gregarious, loud, and social culture; a view of history as a series of missed opportunities; deep mistrust of elites’ capacity to deliver on promises; and even the legacy of Brazil’s military dictatorship.

“Obviously irony is something almost innate to Brazilians. You only have to look at the history of our Carnaval marches. So many of the lyrics relied on sexual double entendres. [Irony] is also our way of dealing with things, of minimizing problems,” says Francisco Junior (Twitter: @fjunior), an editor at a radio station in the capital of Brasília.

And unlike Americans, Brazilians don’t see history as a series of awesome victories. “We like to display our failures. We like to celebrate what could have been instead of what we’ve actually done. Look, we’ve won five World Cups, and the 2014 tournament went pretty well overall. But we’re fixated on 7x1.”

A lot of this has to do with the so-called complexo de vira-lata, a putative national inferiority complex inspired by another World Cup loss, in 1950. It, or the fear of it, hangs everywhere, and Brazilians are just as likely to complain bitterly about their country as they are to angrily denounce others for having the “mongrel complex” themselves. “During the dictatorship and its attendant censorship, jokes, humor, and irony were the forms of protest,” reminds Junior. “And now everyone is just jumping on the internet whenever anything happens.”

Regardless of its origins, this manic, self-deprecatory joking seems to be everywhere online here — probably because Brazilians are just so damn active on social networks. Essentially everyone here is connected, and the fifth-most-populous country in the world seems to spend much more time on social networks than people do in the U.S., says Manuela Barem, editor at BuzzFeed Brazil.

“There’s a big difference between the culture of the English-language internet and ours. Brazilians are much more obsessed with what happens online, to the point of spending hours on the same topic. Perhaps that has to do with their desire to always [be] talking about the same thing, for everyone to ‘be a part’ of what’s going on … it ends up being that they’re just posting way more than an American or English person,” says Barem.

When it comes to the special space for trauma, she says her “impression is that it’s a type of minor catharsis, that comes in the form of irony when we confront a problem or some bad news, and we want to react but there’s no apparent solution.”

Of course, Brazil is now a democracy, and people can say whatever they want. The jokers make it clear, too, that not everything goes. So actual death and trauma (say, a birth defect due to Zika) is not joke fodder, whereas a generalized health crisis and constant, low-level terror, perhaps due to public failure, can be funny indeed.

“You can make fun of [the mosquito genus] Aedes but not microcephaly. I can joke about the Zika epidemic, but the government can’t. They have to treat the problem seriously. We have an inefficient state, the economy is in a bad state, and we lost 7x1. We laugh at ourselves before the world can laugh at us,” says Vera Vanessa, the very active and much-beloved Twitter user @verineas. “If the government doesn’t provide the necessary support … what else is there for us to do?”