|

(Photo: Edward Keating) |

The word in early November that beloved Broadway diner Cafe Edison would soon be serving its last bowl of matzo-ball soup was, unfortunately, not the only devastating closing news of 2014 (see also Smith’s, Pearl Paint, Kim’s Video, Milady’s, Ding Dong Lounge, Rizzoli, and Shakespeare and Company). But while it’s indeed been a particularly brutal year for a certain kind of classic spot, New Yorkers, remember, have long been prone to head-shaking and “back-when”-ing—from the time the last couple met up under the clock at the Biltmore to the day the lone remaining Afghan-rug shop on Bleecker Street made way for Brooks Brothers. Amid the nostalgia-fests and #SaveCafeEdison lunch mobs, it’s easy to forget the stalwarts still hanging on. Here, we offer a spotlight on the places that belong to a dying breed of shop (or mobile knife sharpener, or roller rink), which are in many cases the very last of their kind. Get to these glove-makers, fleabag hotels, Chino-Cuban eateries, dirt roads, and seltzer men while you still can.

|

(Photo: Edward Keating) |

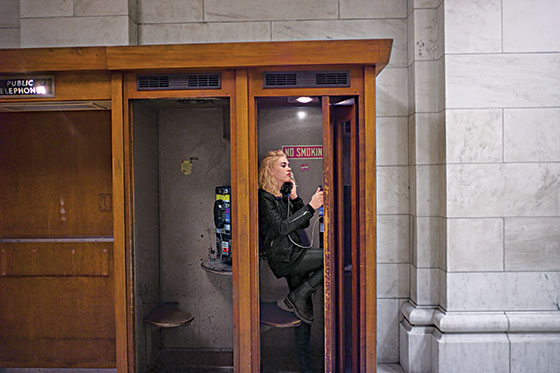

Wooden Telephone Booths

Among only a handful of working wooden telephone booths left in the city (including those at the Harvard Club, the Frick, and Bamonte’s restaurant in Williamsburg) are the three spread across separate floors of the New York Public Library’s Stephen A. Schwarzman Building (above). Installed when the building opened in 1911, these booths include vintage folding doors, wooden seats, electric lights, and ventilation fans. These days they’ve become more of a prime backdrop for selfies, but outgoing calls are still possible for the price of a quarter.

|

(Photo: James and Karla Murray) |

Art-House Movie Rentals

Cinephiles in the city took a gut punch when Kim’s, the St. Marks Place mecca of niche video rentals, closed in 2009 (the last branch, on First Avenue, shuttered this summer). Others like it still remaining: Two Boots Video (42 Ave. A., nr. 3rd St.; 212-254-1441), which opened in 1996 and whose 5,000-title collection is heavy on Criterion, cult classics, and foreign films; Video Free Brooklyn (244 Smith St., nr. Douglass St., Carroll Gardens; 718-855-6130), which started in 2002; and Videology (308 Bedford Ave., nr. S. 1st St., Williamsburg; 718-782-3468), which opened in 2003 as a stand-alone video-rental shop but has expanded with an in-store bar and screening room that shows horror classics like Nosferatu and music-video marathons.

Society Dance Classes

The 1930-founded ballroom-dance school Barclay (its multiple locations include an outpost on the Upper East Side) is one of the last programs of its kind, in addition to the Knickerbocker and the Heights Casino. Here, three alums who went on to put their children through the same white-gloved rite of passage.

"I had a huge crush on this one redheaded little boy. One time, he had a worm in his pocket and he surprised me with it! Luckily, I had my white gloves on.” —Carol Reynolds

"Now my 11-year-old son goes there—we were getting out of a crowded elevator recently and he stood there and held the door for every single person.” —Andrea Donahue

"When my daughter started out, I felt like I was going back in time and looking at myself with the white gloves, doing the Mexican hat dance. I remember anxiously waiting to put the white gloves on for the first time. It was strange and exciting." —Tara Lipton

Stable Row

24th Street east of Madison Square—once known as Old Stable Row because of its saddlers, blacksmiths, and horse doctors—thrived during Edith Wharton–era New York. Now Manhattan Saddlery (117 E. 24th St., nr. Park Ave. S.; 212-673-1400), né Copperfield’s, then Miller’s, is the only remaining equestrian-supply store in the city, selling paddock boots, half-chaps, and horse tack to visiting riders and those who keep horses upstate or on Long Island.

Meatpackers in the Meatpacking District

“It started to change in the mid-’80s. USDA code got stricter, you no longer had the skilled labor—immigrants from Europe or blue-collar American guys coming in and apprenticing. Then Pastis opened up. Then Soho House, and it got on Sex and the City. Our business has managed to survive because the city owns our building, we have a long-term lease. What we do day-to-day is pretty much the same. We’re still cutting beef carcasses here, but demand has changed: Years ago, you’d see the same three cuts: strip, rib, and filet mignon. You wouldn’t see high-end restaurants wanting short ribs.” —John Jobbagy, J.T. Jobbagy Inc. (832 Washington St., nr. Gansevoort St.; 212-633-0130)

|

(Photo: Edward Keating) |

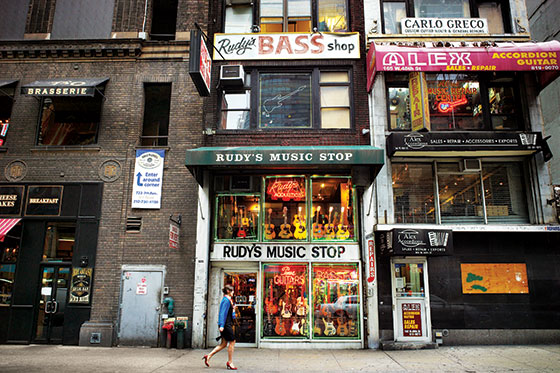

Music Row

Starting in the 1930s, 48th Street just east of Times Square was filled with specialty instrument shops and a few superstores catering to the giants of 20th-century pop and jazz. Most notable in this cluster: Manny’s Music, a favorite of rock stars like Pete Townshend that closed in 2009. Now many have shuttered or moved, and only two remain on 48th Street proper. The original Rudy’s Music Stop (169 W. 48th St., nr. Seventh Ave.; 212-391-1699), founded by Rudy Pensa in 1978, is known for ’70s Gibson electrics and other high-end vintage guitars and basses, along with custom-built models for the likes of Dire Straits’ Mark Knopfler and jazz star Christian McBride. Next door, Alex & Bell Accordions (165 W. 48th St., nr. Seventh Ave.; 212-819-0072) has kept going for 40 years thanks to an international clientele and a recent rush of accordion-playing Mexican migrants.

|

(Photo: James and Karla Murray) |

Manhattan Tackle Supplier

“I bought the business [Capitol Fishing Tackle Company, 132 W. 36th St., nr. Broadway; 212-929-6132] from the original owner’s son, a friend of my father, in 1974, when we were still located at the Chelsea Hotel. Sid Vicious would come in and look at knives, Andy Warhol would come in. People from all around the world knew who we were. Now we’re the only one of our kind, but back then there were at least 26 other real fishing-tackle stores in New York City. There were people fishing off all the piers; I had customers who fed their families fishing. We moved near Penn Station in 2006, and the demand these days is nowhere near as busy as it used to be, but we still have thousands of lures, rods, and reels. The Hudson River is cleaner than ever—there’s bluefish, fluke, and you can’t believe the size of the striped bass you can catch.” —Richard Collins, owner

Working Farm (Not on a Roof)

The 47 acres occupied by the Queens County Farm Museum (73-50 Little Neck Pkwy., Floral Park; 718-347-3276) have been worked since 1697, making the museum the site of the oldest continuously active farm still in existence in the state (not as old, but still very old, is the 200-year-strong El Poblano on Staten Island). It was a family farm through 1926, when the state bought it to use as a rehab facility for a psychiatric hospital. In 1976, it was landmarked and eventually transferred to the city’s Parks Department, which opened the farm to the public. Veggies, alpacas, and honeybees are still raised there.

Roy Rogers

The good old fried-chicken-and-buttermilk-biscuit joint (401 Seventh Ave., nr. 34th St.; 212-630-0327), a chain of about 650 outposts at its peak, is now the last Roy Rogers in the city, sharing a counter with Nathan’s at Penn Station. It doesn’t have the old New York appeal of its food-court mate, but it attracts some nostalgic eaters who remember the chain from its salad days (per Yelp, you should skip the lettuce from the fixings bar, though).

Gunsmith

“My father and uncle were both avid shooters, and my uncle did some amateur gunsmithing. They’re absolutely fascinating devices, built to last generations. We’ve had people come in with guns that go back to the Civil War. They still work, for the most part. I mean, a screw that’s been in a hole for the last 100 years, it’s not going to want to come out nicely. It’s resurrection work on an antique like that.” —Dino Longueira, Majestic Arms, Ltd. (101A Ellis St., nr. Arthur Kill Rd., Staten Island; 718-356-6765)

Slot-Car Racetrack

Named after old-timer owner Frank “Buzz” Perri, Buzz-a-Rama (69 Church Ave., nr. Dahill Rd., Kensington; 718-853-1800), New York City’s last surviving slot-car (remote-controlled mini-vehicles) racing joint, opened back in 1965. A few kids explain why it’s still cool to have birthday parties at this decidedly non-virtual play spot.

"I always play the green car, and my brother always plays the blue, and I always get in front of him on the curve.” —Jackson Schad, age 7

"I went there a long time ago, and I remembered that it was really fun, so I wanted my birthday there. We got to play races—racing the cars is easy because you only actually have to push one button—and after we had cake.” —Patrick McGovern, age 9

"The first time I went, there were a couple of other girls. The second time, I was the only one but I didn't really care. Everybody was yelling stuff like, 'I'm much faster than you!' I yelled, too, kind of." —Veronica Morris, age 7

|

(Photo: James and Karla Murray) |

Peep Show in Times Square

About 20 women ply their trade in six booths at Times Square’s last private peep show. Visits to Playpen (687 Eighth Ave., nr. 43rd St.; 212-445-1731) are not the make-it-rain affairs found at some of New York’s higher-end strip clubs: Rather, customers pay $10 to raise the curtain on a single dancer.

Typewriter Repairman

“My father started the company about 82 years ago. When I was a kid, I helped him spool the ribbons and things, and I officially came into the business in 1959, right during the heyday for typewriters—that lasted until the early ’90s, when more and more requests came in for me to fix people’s laser printers rather than typewriters. But there’s been a resurgence in typewriter sales in the last three to five years. Most of the people who want the typewriters—we repair them when they buy them elsewhere or sell them reconditioned and rebuilt—are the younger generation, everyone from wannabe writers to lawyers to accountants. When they’re working on a computer, they tell me, there’s always a distraction.” —Paul Schweitzer, Gramercy Typewriter Company (174 Fifth Ave., nr. 22nd St., Ste. 400; 212-674-7700)

Big-Screen Porn Theater

The last big-screen porno theater in the city isn’t on some stretch of 42nd Street Giuliani forgot. It’s in an Orthodox Jewish section of sleepy Midwood, Brooklyn. A onetime Deco palace, the Cinema Kings Highway (711 Kings Hwy.; no phone) turned to skin flicks in the ’60s and now screens gay and straight smut in two small, 15-seat basement theaters, while classics and foreign films (like Papillon and the two-part biopic of French outlaw Mesrine) run in the 200-seater upstairs.

|

(Photo: Edward Keating) |

Upper West Side Chino-Cuban Restaurant

Chino-Cuban restaurants became a fixture in Manhattan, and especially on the West Side, after Castro came to power, as many Cuban-Chinese business owners fled the communist regime. The phenomenon peaked in the mid-’70s; now only one of these Upper West Side old-school joints remains: La Caridad 78 (2199 Broadway, at 78th St.; 212-874-2780), where a constant flow of regular patrons consume carne guisada and chicken with broccoli.

Dirt Road

Though there had been efforts to cover the city’s dirt roads with cobblestone going all the way back to the Dutch era, it wasn’t until 1938 that the last public streets in Manhattan were paved over. The only exception was private-access Broadway Alley, which missed out on the asphalt, making it what’s widely believed to be the last dirt road on the island. (Despite the name, the street actually runs between 26th and 27th Streets in Murray Hill, nowhere near Broadway.) For most of its history, it was known as a den of gamblers, stable boys, hoboes, and other Old New York–style sin and depredation. Today, the owners of the various buildings that the alley abuts use it as a service alley.

Gray’s Papaya

One last location (2090 Broadway, at 72nd St.; 212-799-0243) of the venerable papaya-and-hot-dog joint is hanging on. Founded in 1973, it vends dogs that are considered tastier than those at the more numerous Papaya Dog and the much older Papaya King.

Non-Twee Taxidermist

“As of the ’70s, taxidermy was still big, big, big in New York. In Brooklyn alone, there were three or four taxidermists. Now in the five boroughs I’m the only guy. Eighty percent of my business still comes from hunting, as opposed to pets and repair. I’m getting a lot more black bear than I ever did before; there are more black bears in New York State now. For a full black bear, you’re looking at $2,000. People like to keep them in their cabins upstate, but some people keep them in the city.” —John Youngaitis, Cypress Hills Taxidermy Studio(718-827-7758)

Roller Disco

“We opened Crazy Legs (110 Kosciuszko St., nr. Nostrand Ave., Bedford-Stuyvesant; 212-777-3232) in 2008 after the three top rinks in the city—the Roxy, Skate Key in the Bronx, and Empire in Brooklyn—all closed within a year of each other. In the ’70s, the same crowd would go to all those places, and we all knew each other. I was working as a skate instructor at the time, but I had to find a space for a new rink. Our crew finally found one in a Salvation Army gym. We’ll now get 100, 150 people, and we alternate between about five DJs, including Big Bob, who was the DJ at Empire rink.” —Lezly Ziering, owner

Seltzer Filler

“At our shop, we fill the glass bottles for the seltzer-delivery men. There are probably only seven of those delivery people left in the city, and one of them is my son, Alex. New Yorkers know what real seltzer tastes like. With those plastic two-liter seltzer bottles you find in the grocery store, the seltzer is exposed to the atmosphere before it goes to the capping machine. Ours is never exposed. And those home seltzer machines [like the SodaStream], they’re not the same. It’s all about pressure. Good seltzer should hurt.” —Kenny Gomberg, Gomberg Seltzer Works (brooklynseltzerboys.com; 718-649-0800)

Leather Bar

Now in its second incarnation, the Eagle Bar NYC (554 W. 28th St, nr. 11th Ave.; 646-473-1866) transformed from a far West Side dockworker’s bar into a leather club in 1970 after Jack Modica bought the place and painted every surface black. It became a center for the fetish community and gay motorcycle clubs until Modica lost his lease in 2000; the club reopened under new ownership in a nearby former horse stable the following year. The crowd is a mix of old-school leathermen and curious younger guys who are a bit less strict when it comes to fetishwear. It’s a big sponsor of Folsom Street East, the New York incarnation of the famous fetish fair, and hosts an annual “Mr. Eagle” contest.

Fleabag Times Square Hotel

If you still want a touch of the vice-ridden Times Square of the ’60s and ’70s, consider spending a night at the Hotel Carter (250 W. 43rd St., nr. Seventh Ave.; 212-944-6000; rooms from $119). Proof of the grittiness is in these recent TripAdvisor reviews:

"When we opened the closet for first time, trash bags were there and it looked that it had been there for a while."—Alejandra G., October 2014

The shower curtain had mould on it and the loo paper was that cheap kind that disintegrates in your hand.” —Carla S., September 2014

"When I pulled the sheet down, I saw what looked like RODENT droppings"—Sam E., October 2014

Mobile Knife Sharpener

“Nowadays, I get at most 20 people a week. People eat different, you know? And they’re not meat eaters anymore. People will spend $100 on a knife today, then they throw it away. It gets dull, they’re like, ‘I have to go out and buy new knives.’ I’m like, ‘For what reason? You spent a thousand dollars on these knives. Thirty bucks, I’ll make them like new!” I learned from my father, my uncles; they all did this. What I do is old-school—it’s the type of stone I use, the way I use my hands to speed up my stone, it’s everything. I was bred into it. I couldn’t teach it. And nobody does it anymore.” —Mike Pallotta, Mike & Sons Sharpening (718-576-4469)

Bespoke-Glove-Maker

New York isn’t the center of glove-making it was 100 years ago, and the custom-garment industry has taken a big hit, but LaCrasia Gloves (270 W. 38th St., nr. Eighth Ave., Ste. 1603; 212-686-5428)—which started out with fabric gloves in the ’70s, eventually upgrading to leather in a rainbow of colors for a mix of drag queens, club kids, and socialites—has been kept afloat by work for Broadway and, according to co-owner Jay Ruckel, a recent influx of clients with special needs, including those with extra and missing fingers.

German Yorkville

Known more these days for its post-frat inhabitants, at the beginning of the 20th century Yorkville was an epicenter of German New York. Only a handful of establishments from that era remain: Heidelberg Restaurant (1648 Second Ave., nr. 86th St.; 212-628-2332), where lederhosen-wearing waiters serve liter beer steins and potato pancakes, brined pork shank, and veal schnitzels; Glaser’s Bake Shop (1670 First Ave., at 87th St.; 212-289-2562), owned and operated by the Glasers since 1902 and still churning out strudel; and Schaller & Weber (1654 Second Ave., nr. 86th St.; 212-879-3047), co-founded in 1937 by a butcher-charcuterier from Stuttgart (think cervelat and cold-smoked sow lachsschinken).

Velodrome

A velodrome was often set up at the first Madison Square Garden, and by the early 1900s, there were permanent tracks in the Bronx and Brooklyn. The city’s only remaining dedicated bike-racing track is the Kissena Velodrome in Flushing’s Kissena Park. The 400-meter asphalt oval, built in 1962 at the tail end of Robert Moses’s park-building boom, got a $272,000 makeover in 2002 as part of the city’s failed bid to attract the Olympics. Now cycling clubs meet during the spring and summer, and the track runs a youth racing program. It’s the only track of its kind between here and Pennsylvania, though that’s not for lack of trying—philanthropist Joshua Rechnitz only last year abandoned a years-long plan to put a velodrome inside a $50 million field house at Brooklyn Bridge Park.