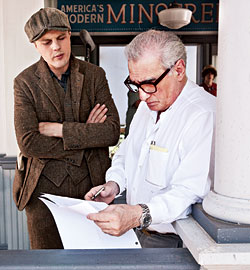

Two years ago, Terence Winter, an executive producer for The Sopranos, was invited to the home of Martin Scorsese. The time was 9:30 p.m., and he had been told it was for dinner. Winter showed up with a bottle of wine. They sat down and started to talk, and as time passed and Winter got hungrier, he realized there was going to be no dinner. But by then, it didn’t really matter. The two were well into planning HBO’s Boardwalk Empire, which Winter wrote and Scorsese helped produce (he also directed the pilot). Over the next year, the two spent hours in Scorsese’s screening room watching thirties Warner Bros. dramas like The Public Enemy,The Roaring Twenties, and Scarface, as well as fictional biopics on real gangsters like Al Capone. “The best film class you’ve ever had,” Winter says. “Martin Scorsese sitting with you watching gangster movies.”

When HBO finally unveils Boardwalk Empire—its sprawling portrait of Atlantic City in the twenties—viewers will see the results of that preparation. It’s one of the most visually sumptuous and detailed productions ever shown on the small screen, and a reaffirmation of premium cable’s indispensability when it comes to provocative, big visions. The thirteen-episode series is based on Nelson Johnson’s history, Boardwalk Empire: The Birth, High Times, and Corruption of Atlantic City, which tells the story of one Enoch “Nucky” Johnson (played by Steve Buscemi and renamed Thompson). During the months they were planning the show, Winter and Scorsese debated how much to update the story. “Should it be a literal description of the twenties, or should we do some stylized, heightened reality and make it our own version?” says Winter. They opted for verisimilitude over beauty, which in this case meant aiming for a kind of shabby elegance.

But shabby is relative: The money spent on Boardwalk Empire is lavish even by the standards of HBO, which is still struggling to replace ratings-busters The Sopranos and Sex and the City. Although the words New Jersey and organized crime initially evoke that other Garden State gangster drama, Boardwalk is in fact more reminiscent of Rome, HBO’s blood-soaked 2005–07 saga. Estimates of that series’s first-season costs ran as high as $100 million, but HBO shared the burden with its co-producer, the BBC. Like Rome, Boardwalk aspires to a top-shelf, whole-cloth re-creation of a place and time long lost, but now the network is footing the bill alone. Industry insiders peg the cost of the season at upwards of $65 million. Variety recently reported the price of the pilot alone at $18 million, though that includes constructing a 300-foot-long actual boardwalk featuring period-perfect replicas of storefronts and seaside attractions, including the then-shocking Incubator Baby.

The “benevolent despot” inspiring all this ambition was Atlantic City’s treasurer. But Nucky Johnson was so much more: In life and on the show, he was a fixer and a mob boss, mobilizing voters to keep the local Republican machine in power and running most of the town’s commercial enterprises, licit and otherwise. The series opens just before midnight on January 16, 1920, when Prohibition went into effect. Immediately after, as Atlantic City found a new, lucrative calling as the key point for contraband booze heading into New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago, Nucky becomes the supplier of choice for the likes of Lucky Luciano and Arnold Rothstein. (Capone, played by Stephen Graham, is one of Luciano’s flunkeys.)

Boardwalk’s trek from page to screen began when Stephen Levinson and Mark Wahlberg optioned the book for their production company, Leverage Management. Wahlberg then got Scorsese interested after working with him on The Departed. Winter, the show’s creator, became aware of it as he was wrapping The Sopranos. “They asked me if I thought there was a series in there,” he recalls. “Then they said, ‘By the way, Martin Scorsese is attached.’ I said, ‘Well, I guarantee you there’s a series in here. I’ll find it!’ ” Then they just had to get the damn thing made.

One massive concession to reality is that not a single frame of the show was shot in Atlantic City, where there simply wasn’t enough of the old town left. Ditto for Asbury Park, where the location team briefly considered a stretch of intact boardwalk. In the end, Boardwalk has turned out to be one of the most intensely New York–centric productions ever made. In all, there were just over 120 metro-area locations that passed for Atlantic City and Chicago, as well as the occasional New York–set scene. Among those, 50 were churches, many of them in Brooklyn. In fact, the show’s fictional Babette’s nightclub, the site of the pilot’s stroke-of-midnight Prohibition party, was created in John Wesley United Methodist Church in Bedford-Stuyvesant.

After setting up its crew and soundstages in Brooklyn’s Steiner Studios in early 2009, recalls Shaw, one of the show’s producers happened to drive past a dormant lot on the Greenpoint waterfront, which, thanks to the cresting recession, yielded a long-term lease. “[The lot] had been cleared for condos to be built, but it was not a good time to break ground.” In fact, no actual ground was ever broken. In the rush to erect the boardwalk set and avoid the delays of an environmental-impact study, the whole thing was built on a massive steel foundation that sits on the ground rather than in it. Incredibly, construction began in late April 2009 and was camera-ready by the third week of July. A strip of ersatz beach was added by trucking in tons of sand.

Knowing exactly what to put on the boardwalk, and everywhere else, and how it should look, was a voluminous research job: In addition to Johnson’s book and Atlantic City newspapers of the period, Winter mentions reading John Dos Passos’s USA trilogy; The Great Illusion: An Informal History of Prohibition, by Herbert Asbury; E. L. Doctorow’s Ragtime; and, more recently, Daniel Okrent’s Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. His historical digging unearthed some eye-opening period arcana. For instance, Winter discovered that in 1920 phone use was still novel enough that people didn’t know what to say when they picked up. “The word hello didn’t exist before the invention of the telephone,” says Winter, so at first people made due with “ahoy,” “hail,” and “greetings.” Viewers will also be struck, in episode three, hearing Chalky White, one of Nucky’s business partners (played by Michael K. Williams, Omar of The Wire) say “motherfucker.” According to Winter, it was a Civil War–era term used as a very literal epithet inspired by a horrific breeding practice (plantation owners would mistakenly pair a son with his mother).

Some of the biggest challenges were faced by the wardrobe department, which had the gargantuan task of clothing a cast that at times numbered more than 150. “We ended up building a lot of [outfits] from pieces of older clothes because the vintage clothing would shred as soon as you put somebody in them,” Shaw says. (The job was a little easier with Paz de la Huerta, who, as Nucky’s moll, is usually out of clothing altogether.)

With HBO all but officially announcing the show’s renewal, Winter’s beginning to worry about what comes next. The year 1920 was bursting with historical phenoms: In addition to Prohibition, there was the onset of a postwar depression, the return of thousands of soldiers from Europe (Michael Pitt plays Jimmy Darmody, a doughboy and Nucky’s renegade protégé), the passing of women’s suffrage, and the conviction of one Charles Ponzi. “I hope something happened in 1921 or I’m not going to know what to do,” says Winter. Luckily “the diving horse didn’t come in till the thirties. Thank God we don’t have to worry about that.” Yet.

Boardwalk Empire

HBO

Sundays. 9 p.m.

Debuts Sept. 19.