’I’m feeling very uncomfortable about your apartment,” said Liz. She was talking to her best friend, Sara, who at the age of 24 had just purchased a cozy one-bedroom (price: $675,000) on the Upper East Side. They were on their way to dinner, two carefully groomed, impeccably dressed young women trying to hail a cab, when Liz’s remark just kind of … slipped out. Sara was startled—“I guess it had just been in her head for so long,” she later told me—though she knew something had been brewing. Until she bought the apartment, it had been easy—and convenient—to overlook how different their lives were becoming. They had known each other since their freshman year at Stuyvesant and had attended the University of Pennsylvania together; they recognized each other immediately as similar products of middle-class Jewish households (Liz grew up on East 18th Street, Sara in Brooklyn) in which a great deal of pressure was put on them to succeed. They spent practically every other day together, talking about books or politics or going out and buying each other rounds of overpriced cocktails and feeling the particular bond of being young in New York City. But now there was this apartment, this doorman building with decent views, starkly highlighting certain developments in their lives. Namely, that Sara was making money and Liz was not.

This was just over a year ago. As they told me the story recently over dinner—gourmet takeout and red wine—at, yes, Sara’s apartment, they laughed about it, emphasizing the whole ordeal as a purely past-tense affair.

Liz: “It was just growing pains.”

Sara: “A dissociation of our lives.”

Liz: “It’s hard. You have these feelings you don’t want to have. It helped just being able to say, ‘I’m envious. I’m proud of you, but I’m jealous.’ ”

The dinner was one of several conversations I had with them as a means of dissecting a pernicious, rarely discussed drama among friends: the way money bores into the dynamic and disrupts fragile equilibriums. I met them after sending out an e-mail to friends and acquaintances asking if anyone knew a group with the “sense of humor” required to talk openly about money. The responses ranged from the anxious (“I wouldn’t know where to start”) to the vaguely accusatory (“Are you insane?”), but a few were willing to go along with it. In addition to Liz and Sara (who asked to be called by her Hebrew name), I also spent time with their close friends Alex and Michelle (who asked to go by her middle name) and met another member of the group whom I’ll refer to as Miss X (she both comes from serious money and makes serious money and elected not to participate in an article on the subject). Like many friends in New York, they’re bound by a paradox: living similar lifestyles on massively diverging budgets. As a Ph.D. candidate in neuroscience at Rockefeller University, Liz receives a $23,000 annual stipend; Sara works in finance, in a job where she can expect a significant raise every year or so, and now earns what she describes as a “low to mid” six-figure salary. Both Alex and Michelle work in advertising, earning “mid to upper” five-figure salaries, though Alex, a fellow Penn alum, has years of loans to pay off.

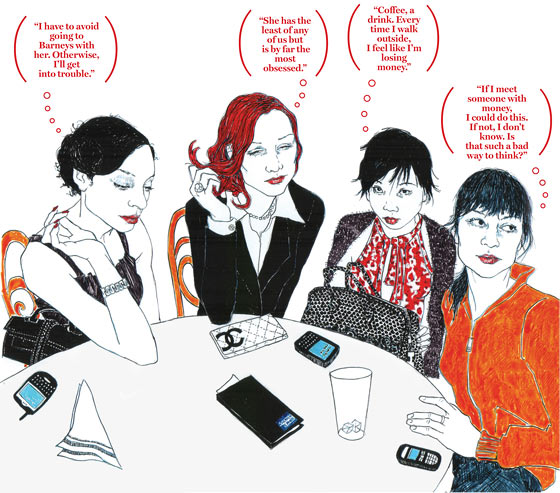

Genuine friendships are a connection, of course, not a transaction. But in a city where money has a way of becoming the subtext of every exchange—where just choosing a restaurant can carry relationship-straining implications—certain snags and fissures are inevitable. Take Sara and Liz. It’s one thing for Liz to have admitted jealousy, another to eradicate it. Ever since the apartment became an issue, Liz has developed a habit of turning almost any topic into a conversation about money—specifically, about everyone in New York having more than her—which wears thin on Sara. (“Liz has the least of any of us,” Sara told me privately, “but is by far the most obsessed.”) They both admit that they no longer see each other as often, that they are not quite as open as they used to be, and that, for better or worse, they understand why. Though they grew up in the same city, they have come to inhabit entirely different New Yorks.

As if to illustrate this, Liz invited me to see her apartment after dinner at Sara’s. “Just so you can compare and contrast,” she said as we walked down East End Avenue and through the gates of Rockefeller University—only a few blocks but many psychic miles away from Sara’s. Liz lives in student housing, which she sublets when she’s out of town to help pay for vacations like the trip to Spain she took with Sara and Alex a couple of years ago. The fluorescent-lit, linoleum-floored one-bedroom, furnished in Classic American Dorm Room style, is spacious by New York standards, 500 square feet or so, but it’s a space in which it is almost physically impossible to feel like an adult. For Liz, who is 26, I can imagine this getting old.

“Oh, wait, you gotta see this,” she said as I was leaving. She opened the freezer, which was packed with frozen meats and cheeses purchased by her mother at BJ’s, the bulk-discount store. “We go shopping there every six months. That’s how I can afford to go out with my friends.”

Imagine the four of them at dinner—Liz, Sara, Alex, and Michelle—talking about work, about men, about what the Democrats need to do to get their act together. What they don’t bring up, ever, is money. A somewhat subconscious omission, it’s also a function of necessity: the maintenance of an illusion, a way for them to believe that they are the same. But even among friends—especially among friends—the illusion has a shelf life. The check comes. Handbags—some newer than others—are reached for. The bill is split. For Sara, it’s a splurge with no lasting reverberations. For Liz, it’s something she is able to do—occasionally—because she is a “very clever budgeter” who supplements her income by babysitting, dog-walking, coat-checking, and selling things like old cell phones on eBay. For Michelle and Alex, it’s something in between: a reminder of why neither has any savings.

Alex and Michelle, both 27, are in almost identical financial situations—similar salaries, similar spending habits—and are seemingly all the closer for it. When they go shopping together, they try on everything, pretending they can afford it all but purchasing just one or two items. Both guessed they spend about $500 a month on clothes and beauty products. Alex jokes about how her savings account isn’t really for putting money away, “it’s just sort of like delayed spending.” Michelle—who’s single and happy to live in her Soho studio for many more years—doesn’t think twice about this lifestyle. “Unfortunately, I have good taste” is how she put it, as serious as she was sarcastic. She wouldn’t mind having an apartment big enough to entertain in, but she has friends with money, like Miss X, and when she feels the urge to throw a dinner party, she calls them up and asks if she can cook them dinner.

Alex, on the other hand, has started to question the sustainability of an adult life that feels like an extension of adolescence. She’s been living with her boyfriend for two years, and wants to start a family sometime soon(ish). Raised in Virginia, she’s thinking that one day she’ll leave New York for a place where you don’t have to think so much about money. “In Manhattan, you can’t help but have an attitude of consumption,” she said. “You walk down the street—all those ads are for you. Even going to meet friends is about consuming. You don’t meet at a park bench—you get coffee, you get a drink, you have to buy something. Every time I walk outside, I just feel like I’m losing money.”

The idea of Alex leaving remains too much of an abstraction for Michelle to really worry about. When I asked her about where she noticed money affecting her friendships the most, she brought up Miss X, who operates on a seemingly limitless budget. “I try to avoid going to Barneys with her,” Michelle told me half-jokingly. “Like, maybe just once a month. Otherwise, I’ll get in trouble.” During a recent outing, Miss X bought a $600 sweater. “I would never do that,” Michelle said. “If I really ‘needed’ a $600 sweater, I would maybe, like, get it in double discount or mention to my parents that I need really nice sweaters for Christmas because I’m so cold.”

Then there is the matter of vacations. When New Year’s plans were recently discussed, Miss X brought up the idea of spending a long weekend in Croatia, or maybe the Maldives, which Michelle and Alex took to mean the group wouldn’t be spending the holiday together. “Last year, she wanted to go to the Dominican Republic and was like, ‘If you can’t afford it, just ask your parents for Christmas,’ ” said Michelle. “I can’t have the same dismissing quality that she can—oh, a weekend in the Dominican Republic!” Both Michelle and Alex stressed that this doesn’t stir any animosity or envy on their part. In fact, they point out, Miss X can be quite generous, loaning Michelle money when she moved into a new apartment. But there is some distance where before there was none. “Three years ago, we would spend every single weekend together,” Michelle said. “Now there are some weekends where I don’t see her. But I think that’s also, like, healthy for us.”

Bring up Miss X’s wealth around Liz, on the other hand, and within five minutes she’ll run the gamut from aggravated to embittered to confounded to repelled to even more aggravated. Back at our takeout dinner at Sara’s, not long after assuring me that she no longer felt any resentment over Sara’s apartment, Liz turned the conversation back to real estate. This time, the object of understandable envy was Miss X’s recent apartment purchase for an amount that not one of the other girls could even conceive of touching: $1.5 million, rumored to have been paid in cash.

“Every time that apartment comes up, I just have to leave the room,” Liz huffed, her cheeks flushed, her arms gesticulating wildly. “What drives me nuts is that she does not credit Mommy and Daddy! I cannot handle it! When someone I am ‘friends’ with spends $1.5 million on something, and I can’t ask her where she got the dough? She’s under 30! There’s no way I can be down with that. I will just lose my shit!”

For Liz, Miss X’s apartment—the price of it, the casual attitude toward it—has taken on a symbolic, somewhat perverse meaning: proof that the New York of Liz’s childhood no longer exists. The sale of Stuyvesant Town devastated her, and she often complains about how the city is being overrun by “bankers and banker spawn.” And when she confronts the fact that some of the wealthy people making the city less affordable are her own friends, the issue becomes even more loaded and distressing. “We’re not talking about some shack!” Liz continued. “We’re talking about some nice apartment that my parents could never afford. Give some respect to the purchase. Otherwise, I’m sort of like, you’re an asshole!”

Sara, who recently quit smoking, stood up and searched out an emergency pack of cigarettes. As Liz went on about Miss X (She thinks the average salary is $1 million! She lives in a different fucking universe than I do!), I watched the expression on Sara’s face change. The easy smile had morphed into a tense glower. It turned out that what bothered her wasn’t just the way Liz was talking about a friend—Sara could sympathize with Liz’s struggles—it was that Liz had a way of being more forgiving when it came to men with money.

“I think you make snap judgments about people if you don’t have romantic intentions,” Sara said, opening up a second bottle of wine.

“That is not true!”

Sara turned to me. “Liz will let herself get manipulated and hurt by people she gets involved with because they’re rich and they’re Jewish. ”

“I don’t want to get into this,” Liz declared. “The degree of psychosis that I have when I’m dating is pretty severe. It’s not linked to money. Well, it is, maybe.” She shook her head, as if trying to purge the thought from her mind. (But days earlier, she had admitted as much to me: “It’s like this,” she had explained. “I want to live in New York and I want to be a scientist, which means I’ll probably never make very much money. If I meet someone with money, I could do this. If not, I don’t know. Is that such a terrible way to think?”) Over dinner, Liz eventually said to Sara, “Who I date and who I am friends with are very different things. It’s not consistent, but …” She waited for the thought to gel. “My approach to all relationships is different and retarded.”

Sara seemed satisfied with this, put in a better mood. I asked her how she felt about Miss X, if she was bothered by her wealth and nonchalance.

“It’s hard. You have these feelings you don’t want to have. It helps being able to say, ‘I’m envious. I’m proud of you, but I’m jealous.’ ”

“I don’t react that way to money,” she replied. “I’m much more stoic. More than that, I know the world that she travels in. I’ve studied with them, I’ve worked with them. To them, it’s not a big fucking deal.”

“Exactly,” said Liz.

This conversation—not particularly pleasant as it happened—took on a vengeful life of its own in the days that followed. Sara was clearly more bothered than she had let on, and related every nuance (what Liz said, how Liz said it) to Alex and Michelle, who related it back to Miss X, who then sent me a caustic e-mail for starting the whole thing. Over the next day or so, I became something of an inadvertent (and ineffectual) moderator in a nasty four-way argument. Liz was on the outs. Michelle was siding with Miss X. Sara, her loyalties torn, decided it was all too stressful and didn’t want to talk to me anymore. “As you can see, it’s just raised too much shit,” she said before hanging up.

The whole affair made a twisted kind of sense. You go to write a story about how money can come between friends, and suddenly you’re watching money come between a group of friends because of a story you’re trying to write. To encourage friends to discuss their relationships in terms of money is perhaps inevitably to hasten the end of those friendships.

Everyone stressed that money wasn’t the “real” problem here, just a catalyst making other long-festering “issues” impossible to ignore. And maybe that’s true: Friendships are complicated, and an outsider can never have the full story. They’re also wonderfully resilient and—who knows?—it’s possible that Liz, Sara, Michelle, Alex, and even Miss X will make peace and agree to never again talk about average salaries and shopping sprees, to tiptoe around the subjects of expensive apartments and vacations.

Then again, maybe not. As Liz told me, “I’m closer now with my friends who live in Brooklyn and don’t have any money. We come from a similar background, and that’s who you want to be friends with—the people you relate to.”