Illustration by Kagan McLeod

It’s 9:57 a.m., and David Glass is walking down Broad Street, his feet falling hard on the December sidewalk. Sniffling from a head cold, the 32-year-old day trader looks straight ahead, barely registering the gift-shop windows filled with executive golf putters and bull and bear figurines. His cell phone startles him. “Yo,” he answers, betraying nothing. “Sorry, I meant to call you last night.”

With a deep breath, Glass enters the fluorescent-lit brokerage office of his firm, Jasper Capital. He high-fives friends, curses an investor who pulled $1 million from the firm, pecks out instant messages on his computer, asks about football scores. CNBC blares in the background. “What price are you short at?” he asks another trader. “$22.70? Oy! Right in the tush.”

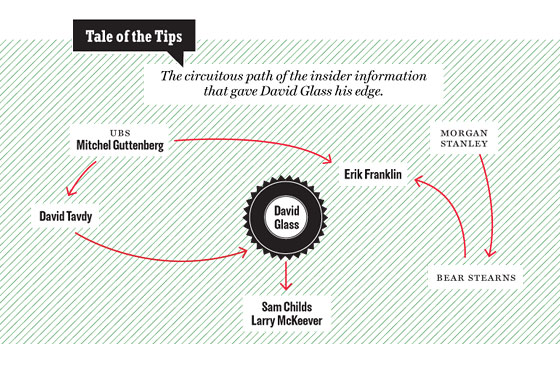

He might be any trader at any firm in the financial district, but not today. Today, he’s wearing an FBI wire, preparing to coax a colleague into incriminating himself for agents listening in a van down the block. The Securities and Exchange Commission is cracking down on what one official calls “one of the most pervasive Wall Street insider-trading rings since the days of Ivan Boesky and Dennis Levine.” On the elaborate chart the U.S. Attorney will later use to diagram the crimes, arrows trace the flow of illegal stock tips from name to name, from an investment banker at UBS Securities to two hedge-fund traders to two others at Bear Stearns. The arrows multiply, travel down through every echelon of Wall Street, from a lawyer at Morgan Stanley and her husband to a broker in Florida, and further down still, thirteen people in all, with one accusatory arrow aimed at Glass himself. Wearing the wire is his chance to stay out of jail.

He approaches the office of Sam Childs, a compliance officer paid to enforce SEC rules whom the commission hopes to nab for allegedly demanding money from Glass in exchange for keeping quiet about the insider-trading scheme. Glass closes the door and sits down. In a conspiratorial whisper, he says he’s worried the SEC might be closing in on the man at the top of their food chain, the one passing along the inside information. That means the monthly payments to Childs will have to stop. The hidden microphone captures the rising tension.

Childs: That puts me in a really weird position, all right?

Glass: Wait, how does that put you in a weird position?

Childs: Well, I’m fucked financially, because I was counting on it …

Glass: Dude, I’ll work something out. I’m just saying, though, if I’m not going to eat, then tough.

Childs: I don’t know, I said that you could have paid me all at once … I didn’t want it to be like that, where every month he was paying. Now I really gotta be careful with what I say to them.

Glass: It also would’ve looked bad, to take a $100,000 check.

Childs: I know. But now because I’m screwed out of the whole thing, I can still go down on something.

Glass: You go down? On what? You can’t go down on anything. You’re not connected to this at all.

It’s a sterling performance. Two months later, Childs, along with everyone else in the ring, would be arrested.

To understand why more than a dozen successful, well-paid professionals would risk their careers and reputations—not to mention jail time—to trade on illegal stock tips, one must only look at the way Wall Street has changed in recent years. Making, say, $3 million a year used to be enough. Now hedge funds flip stocks like so many casino chips, reaping millions in a day, raising the stakes, stoking the envy, leaving everyone hungry for a larger piece of the ever-growing pie. Did you hear about the hedge-fund trader who lost $6 billion on one bad trade? He got fired, spent a few months on the beach, and returned to raise millions for a new fund. No penalty. No limits. Just monstrous sums of money. And the greed, it would seem, has gone viral.

The stock market today isn’t so much about stocks as it is about stock movements. Hedge-fund traders don’t just invest in securities; they move markets, fundamentally altering stock valuations through the sheer size of their positions. When the price of Apple Inc. drops fifteen points not long after it announces a strong earnings report, it’s usually because of a hedge fund cashing out, the smart money exiting the building. As for the average investor buying stocks based on news reports and SEC filings—on the actual value of an underlying business? He’s the sucker at the table, the easy mark. Learning where a stock is headed only after hedge funds have already driven it up or down, he doesn’t have a prayer—and neither do smaller traders like David Glass. Glass needed an edge. And if he happened to find a little inside information, he figured, it would be justice, not a crime—the only way to beat a system that had become stacked against him.

It wasn’t just about the money for Glass—or if it was, the money was simply a means to an end. He had always wanted to be a player on Wall Street. And why shouldn’t it be possible? Hedge-fund managers like Steve Cohen and Ken Griffin used the same trading skills he had to transform themselves into billionaires with 32,000-square-foot mansions and $500 million art collections. Even his older brother was moving up in the world of hedge funds. At a recent Knicks game, David introduced him to friends as “the Mayor” because he seemed to know so many Wall Street bigs in the stands. But Glass himself had never managed to rise in Wall Street’s pecking order.

Growing up in the working-class suburb of Willowbrook, on Staten Island, Glass was always in the shadow of his brother, the “good son” who continued the family’s immigrant success story. His father was an IRS arbitration lawyer, his mother a schoolteacher. They were Orthodox Jews raising four kids in a sleepy Jewish enclave, their lives centered on Young Israel, the largest synagogue in the borough. Glass’s brother was a slow-and-steady sort who played by the book. He studied finance at Queens College and started his career as an accountant. Closer to his parents than his younger brother, he wore a yarmulke and always came home for Jewish holidays.

David Glass had different talents. When he was 9 years old, he bought a bag of five-cent candies and sold them to friends for 25 cents apiece. By his sophomore year at Queens College, he had established his first business enterprise: He ran two blackjack tables out of his apartment on 72nd Avenue in Queens, making $15,000 to $20,000 a week, according to a close childhood friend who attended the gambling nights. “He was a smart guy, and if there was a way he could make the odds in his favor, he would,” says the friend. “There was always a sucker in the room. He would never be that sucker.”

The money must have seemed like a vindication of sorts: His older brother was then an entry-level accountant making less than $30,000 a year.

After a summer internship at PaineWebber, Glass decided to leapfrog to Wall Street by dropping out of school a year early to work for Sterling Foster, a brokerage in Long Island. Sterling Foster was a classic “pump and dump” scam, in which phone salesmen would sell unsuspecting investors on stock in obscure tech companies, bidding up the share price so Sterling Foster’s owners could quickly cash out when the stock peaked, leaving their clients holding the bag.

While Glass was working there, his brother introduced him to Ben Younger, a fellow Queens College alum and an aspiring filmmaker from the neighborhood. Younger needed work, so Glass got him an interview at Sterling Foster. “He was my friend’s younger brother, and he was driving a new sports car,” Younger told New York Magazine in 2000. “This guy tells me, ‘Look, you work here for a year, you make your million bucks, go to the Bahamas, then you can write.’ I was like, ‘Um, I’ll check my book, but I’m pretty sure this fits into the game plan.’ ”

Younger decided instead that he’d found his movie idea. “I walked in and immediately realized, This is my movie. I mean, you see these kids and you know something is going on. I was expecting guys who went to Dartmouth, but they were all barely out of high school, sitting in a room playing Game Boys.”

The film that resulted was Boiler Room. A morality tale about working-class strivers involved in a stock scam during the dot-com era, it starred Giovanni Ribisi as Seth Davis, a streetwise Jewish kid from the outer boroughs who runs an illegal casino out of his apartment before dropping out of college to work at a shady Long Island brokerage called J.T. Marlin. Based in part on Glass’s detailed descriptions of Sterling Foster, Boiler Room showed bullying salesmen recruiting fresh-faced twentysomethings in ill-fitting suits with promises of millions. The boy-men aped Gordon Gekko’s speeches about greed. The top salesmen used their money to buy gigantic unfurnished houses and expensive sports cars, spending wildly on weekend bacchanals of liquor, drugs, and women.

Although he enjoyed the mythic status the movie conferred on him, Glass complained about not receiving royalties from Younger, who had Glass sign a waiver relinquishing his rights to the film. “He sat down with the guy and pretty much gave the guy the whole movie,” says Glass’s childhood friend. “He thought he was going to get some money, and they didn’t give him anything.” (“That makes two of us,” says Younger, who says he got only $15,000 for the script.)

Glass made money at Sterling Foster, but he was too junior in the company to get rich. When he saw friends making $100,000 in an afternoon of day-trading, he took the leap in 1998, eventually landing at Broadway Trading, one of the first professional day-trading companies on Wall Street. He worked under Jonathan Petak, a trader from a similar Jewish background who had worked at traditional brokerages before dropping out to trade on his own. Petak was so revered at Broadway Trading that his computer screen was broadcast on TVs throughout the trading floors, so newbies could watch how he worked. A quick study, Glass became his star pupil, one of the few who consistently made money.

In 2001, Glass married a woman he’d met in a bar in Manhattan. It was an auspicious match: She was a sales associate in a brokerage company and the daughter of a prominent Goldman Sachs money manager. Coincidentally, she had grown up just seven blocks from the Glass family’s two-story house on Staten Island. Her father, also an Orthodox Jew, gave Glass his blessing and helped the couple buy a $1.3 million apartment in Brooklyn Heights. When Glass started his own firm in 2002, he named it after the street that his well-to-do in-laws lived on in Willowbrook: Jasper.

While his brother was still slaving away as a salaried accountant, Glass, the college dropout, had his own business. Before long, Jasper Capital would employ roughly 250 people and trade 350 million shares a month, with Glass getting a commission for each share traded. By 2006, he told associates he was making between $2 million and $3 million a year. It looked as though David Glass had succeeded on his own terms.

The chain of events that would eventually cause the downfall of David Glass began before he had even started Jasper Capital, and involved people he has never met. It all began with Mitchel Guttenberg, a mid-level UBS executive who owed $25,000 to a hedge-fund trader named Erik Franklin. In 2001, at the Oyster Bar in Grand Central Terminal, Guttenberg allegedly offered to tip off Franklin to upcoming UBS analyst ratings as payment. It was valuable, and illegal, information: A “buy,” “sell,” or “hold” rating from UBS would move a stock in a predictable direction, so Franklin could buy before a recommendation went public and sell once the stock moved.

Franklin’s arrangement with Guttenberg apparently worked out so well that he allegedly began a similar exchange with a trader at Bear Stearns who was getting advance word about upcoming mergers and acquisitions passed down from a compliance lawyer at Morgan Stanley. The market was in free fall after the dot-com crash, and the tips moved from trader to trader, down through the Wall Street food chain, like some kind of sure-bet lifeline. Together, the flow of illegal tips generated millions of dollars.

The UBS tips traveled farther and wider than the Morgan Stanley tips, eventually generating $14 million in illegal profits, according to the government. And that was thanks in large part to a man named David Tavdy. Tavdy, a Russian immigrant living in Forest Hills, knew Guttenberg from their days at First Albany bank. The two friends allegedly decided that Tavdy would trade on Guttenberg’s tips and they would split the profits. Tavdy was day-trading through the Queens branch of Assent LLC, a company that rents trading terminals—the same company where David Glass launched Jasper Capital.

One day in 2003, Sam Childs, a compliance officer at Assent, noticed Tavdy’s unusual trading patterns: large positions on a single stock the day before it happened to be upgraded by UBS. Childs didn’t turn him in. Instead, according to an FBI recording, he merely warned Tavdy, telling him he needed to start losing a few hundred dollars so his remarkable winning streak didn’t look so suspicious. (Tavdy’s lawyer disputes this.)

Childs and Glass were friends from Broadway Trading, where they both learned the art of day-trading. Now that Glass was at Assent, Childs was helping him build his business by recruiting high-volume traders—for a fee, of course. He also allegedly told Glass about the trader with the magical ability to predict UBS ratings calls. For “cash kickbacks,” the government claims, Childs gave Glass secret access to Tavdy’s trading patterns. They never met—Glass was working out of the Manhattan branch, Tavdy in Queens—but Glass knew Tavdy’s trades intimately. If Tavdy bought 2,000 shares of Dow Chemical for $50, Glass bought at the same price; if Tavdy sold the next day at $55, Glass sold also. Tavdy seemed to always win, and never lose. Just like that, Glass had found his edge.

As Jasper grew, Glass became quite a presence within Assent, running the equivalent of a boys’ club at his 39th-floor office near the Stock Exchange. He hosted daily poker games between bouts of stock trading. And on Thursdays in the summer, he took all his traders out for drinks at Ulysses, a popular Irish pub in the financial district, spending upwards of $2,000 an outing. As proof of his success, Glass once toted a book bag around the office containing two gold bricks he bragged were worth $18,000 apiece.

His savvy in beating the system had become legend. When the SEC began regulating a common trading practice of betting against a stock the instant it begins to decline—what traders call “shorting on the down tick”—Glass concocted a complicated formula that allowed him to continue the practice while obscuring the move to SEC observers. It took him only three days. Says one Assent trader: “The dude is a frickin’ hustler.”

But Glass wasn’t the only one with access to Tavdy’s trades. Others at Assent heard whispers of the “UBS guy,” and eventually as many as 30 day traders in multiple groups began copying Tavdy’s moves, according to Sam Childs in the FBI recordings. “This thing’s so deep,” he told Glass. By 2005, the rampant insider trading worried Childs sufficiently that he finally asked Tavdy to leave Assent before he jeopardized the whole company. After three years and, according to prosecutors, several million dollars in illegal trades, Tavdy was out in the cold.

It might have ended there—except that two of Tavdy’s Russian friends working at Assent set up a meeting between him and Glass. Tavdy needed a trading desk, and the Russians knew of Glass’s willingness to bend the rules. According to the government’s narrative of events, Tavdy told Glass that “a UBS employee was providing [Tavdy] with the UBS Inside Information and that [Tavdy] and the UBS employee were splitting the profits from the scheme.” If Glass didn’t know exactly how Tavdy had been getting so lucky before, he did now. In exchange for continued access to the tips, prosecutors say, Glass agreed to let Tavdy trade at Jasper Capital using a fake account—one registered in someone else’s name, making Tavdy invisible to Assent’s compliance officers.

For Glass, Tavdy must have been an attractive advertisement for easy money. Born in the former Soviet Union, he now owned a beachfront condo in Miami, a cigarette boat named Enough Is Never Enough (which he renamed Exodus), and a small fleet of sports cars, from a Porsche 911 to a 2006 Aston Martin. As their partnership blossomed, Glass and Tavdy became friends, planning a vacation together during the Jewish High Holidays in Florida, where Glass’s Goldman Sachs father-in-law has an apartment in Bal Harbor, a swanky Miami neighborhood.

To judge by the trades the government has cited as evidence, Glass and Tavdy bought and sold in relatively low volumes, usually earning profits in increments of about $10,000—$165,000 at most—presumably to avoid detection. Over time, Tavdy was able to rake in more than $6 million, according to the government. It’s unclear how much Glass made illegally: hundreds of thousands certainly, possibly millions counting the trades he made before going into partnership with Tavdy and passing the point of plausible deniability. By the fall of 2006, Glass seemed to be spending more money than usual, throwing a lavish birthday party for his wife at a posh private club in the West Village and giving her an enormous round-cut diamond ring he told colleagues cost him more than $50,000. Glass also bought an $85,000 BMW M5 like the one Tavdy had.

Glass was clearly doing well, but his brother was catching up. The accountant was steadily rising through the ranks at a $2.5 billion hedge fund.

In Boiler Room, Giovanni Ribisi’s character is apprehended in an FBI sting and forced to cooperate in taking down the scheme. In reality, David Glass escaped that fate, leaving Sterling Foster before 23 brokers were convicted of securities fraud. Now, however, his life is taking on an uncanny likeness to his fictional doppelgänger.

In late 2006, the SEC filed a request to see Jasper’s entire trading history. No one knew exactly how they had zeroed in on Glass’s company, but everyone at Assent was nervous. By that point, hedge-fund manager Erik Franklin, the first alleged co-conspirator with UBS’s Mitchel Guttenberg, had pleaded guilty and cooperated. That would have led the SEC to surveil the market for suspicious trades in relation to UBS ratings. And that would have led them to Jasper. Glass closed Tavdy’s fake account, but it was too late. The FBI had discovered the illegal trades, and they confronted Glass with evidence.

Glass hired an expensive lawyer, Benjamin Brafman, and agreed to plead guilty and cooperate, too, hoping to reduce his sentence and protect the reputations of his father-in-law at Goldman Sachs, his father at the IRS, and his brother at the hedge fund. Glass, who now has a 3-year-old son, faces a maximum of 25 years in prison and $5.3 million in fines. (Glass declined to be interviewed.)

The FBI had plenty of evidence against Tavdy: Glass had signed up for a monthly service with AOL Instant Messenger that archived every text exchange he made on his computer—meaning there were thousands of pages of conversation between him and Tavdy. What they wanted was evidence against two of Assent’s compliance officers, Sam Childs and Larry McKeever. A year into Glass and Tavdy’s partnership, McKeever, possibly tipped off by a rival trader, figured out that Tavdy was back at Assent, operating under Glass’s umbrella. He and Childs confronted Glass about Tavdy’s account. The government claims the compliance officers demanded money in exchange for their silence: $100,000 for Childs, $50,000 for McKeever. But the FBI needed taped confessions to prove it. Glass’s sentence would hinge on whether he could deliver them.

Making the decision to turn state’s witness is one thing, getting a colleague to incriminate himself in a private conversation is another. Glass was wired for three days in a row. His first attempt to coax Childs into confessing—when Childs expressed disappointment that the payments would have to cease—failed to meet the investigators’ needs. Afterward, Glass is heard calling an FBI agent, who tells Glass he didn’t get the goods. Hearing this, Glass lets out a low moan of agony—the most revealing and emotional sound he makes in the entire recording. “You guys are going to have to be thrilled with that,” he stammers. “It was everything.”

Traders heard whispers of the “UBS guy,” and before long, as many as 30 people were following the illegal stock tips: “This thing’s so deep.”

The next day, Glass returns to the office to speak with Childs again. In this recording, Glass raises the urgency, affecting deep anxiety and paranoia. Repeatedly, he asks Childs if he’s concerned about the SEC’s discovering the payments. Childs dismisses any reason for worry, and he attempts to justify his actions. “[What] the fuck am I going to do?” he says. “The alternative, to me, is blow the whistle on the whole situation … Assent would probably be shut down, day-trading would get a bad name … It’s like, nobody would have gained from doing the right thing. Nobody.” He leaves him with a bit of advice about the SEC’s inquiry: “Don’t let it be all-consuming. Don’t go hiding all your money. Yet.”

On day three, Glass is back to talk to the other Assent officer, Larry McKeever. A 46-year-old father of two, McKeever has heard about the rising paranoia over an SEC inquiry. He has studiously avoided talking on the telephone, according to Childs, concerned that his lines are tapped. But with Glass, he is not so careful. McKeever anxiously suggests they tell the Feds the payments are merely a consulting fee for his bringing Jasper Capital a “big fish”—trader talk for a large investor.

McKeever: Can you think of any other thing why you gave me X amount of dollars? A big fish? A couple of big fishes?

Glass: Yeah, I can make up stories, but, I mean, Tavdy—Tavdy knows the name Sam Childs and I think he probably knows the name Larry McKeever.

McKeever: Listen, Glass, I kid you not—he’s a fucking dead man. I don’t give a fuck if he’s tied into the Russian mob or whatever. I’ll find that cocksucker, mark my words. My lips to your ears. He don’t know my name. How does he know my name?

Finally, McKeever suggests that they pass off the payments as an investment in a fake business venture called “Glass-Mack.”

McKeever: How’s that? I’m working on the strategies and you’re the financial backer, 60-40. All right, can you do that?

Glass: To cover up the payments, we should enter into some kind of partnership?

McKeever: Yeah.

That was just what Glass—and the investigators—wanted to hear.

Starting in January, David Glass came into the office less and less and eventually not at all. One day he’d tell people he was feeling sick, other days he was having family troubles. According to one Assent trader, when somebody asked Glass if everything was okay at home, Glass said, “Say a brucha for my son, Max,” using the Hebrew word for prayer and insinuating that his son was fatally ill. (Another trader says Glass was joking.)

Rumors began to circulate that something wasn’t right at Jasper. A week before the indictments were announced, an online-message-board poster named Blue Thunder warned fellow traders on EliteTrader.com: “Shady characters running Jasper. Watch out!!!”

When the bust was announced on February 28, Tavdy was arraigned in Miami, and Mitchel Guttenberg in Manhattan. Childs and McKeever were each arraigned and released on $250,000 bail. “Today’s events should send a message to anyone who believes that illegal insider trading is a quick and easy way to get rich,” said Linda Chatman Thomsen, the SEC’s enforcement director.

But the lesson fellow traders took away from Glass’s troubles wasn’t what the SEC might have hoped. Insider trading? It happened every day. A friend of Glass’s says he would have done the same thing—anybody would have. As Glass told an associate after his indictment, “I don’t know of any traders who haven’t acted on a stock tip.”

Though Glass’s lawyer says they have no idea what his sentence will be, Glass has told friends that he likely faces eighteen months in prison—a bum deal, they say, considering Glass was just a low-level player in the scheme. In October, the lawyer at Morgan Stanley and her husband, who were at the top of the insider-trading pyramid, were sentenced to just six months’ home confinement for their roles. Glass was “furious” at the news, says his childhood friend, claiming it proved that insiders with connections could get off light while low-end hustlers like Glass were hung out to dry in the SEC’s attempt to prove to the investing public that they’re upholding the integrity of the markets.

“He was always looking for the edge,” says Glass’s former mentor Jonathan Petak. “In a wrong way, I think. If he would have played by the cards, he would have been a lot more successful.” For a case in point, he need only look to his older brother. At precisely the moment of Glass’s disgrace, his brother was experiencing his greatest success: Days after the bust, he launched a new hedge fund.

Glass seems somewhat philosophical about his fate. “Greed’s a killer,” he said to his childhood friend. But that friend says Glass is privately devastated. “He lost everything for nothing.” In a statement issued by his lawyer, Glass says, “I have accepted full responsibility for my criminal conduct. I offer no excuse or defense. I broke the law and I am deeply remorseful.”

But contrition has its limits, especially for a born hustler. Former colleagues claim Glass is already back on Wall Street, financially backing another group of traders in a lower-Manhattan day-trading firm. Not that Glass is advertising it: Two people say they spotted Glass in July entering a day-trading shop located just one block from Jasper’s old offices. When he noticed a former colleague, Glass yanked his blue baseball cap down and lifted a newspaper in front of his face.