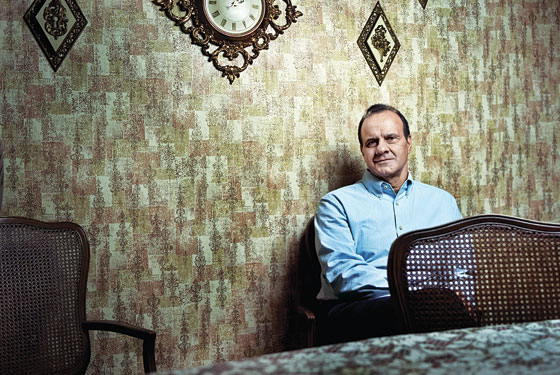

Joe Torre looks terrible. It’s nearly midnight on the south side of Chicago, underneath the soulless concrete bowl of a stadium that is home to the White Sox. Torre sits in the eight-by-eight cinderblock cell that serves as an office for visiting-team managers, sounding utterly sincere in response to postgame questions he’s heard at least 10,000 times before. With the last Japanese reporter shooed out the door, Torre removes his Yankees hat, revealing a scalp with a few lonely tufts of black hair sticking straight up. He starts to stand, slowly. His right knee, ruined by seventeen years playing in the majors, needs replacing, soon.

And this is a good day. About a half-hour earlier, Torre climbed from dugout to field to join the handshake/fist-bump line that forms after victories. Two pillars of Torre’s success as Yankees manager awaited with special gifts: Mariano Rivera, the all-time-great closer, handed Torre the game ball. Derek Jeter, normally all business even after the final out, wrapped the man he still refers to deferentially as “Mr. Torre” in a warm hug. The celebration was in honor of Torre’s 2,000th win as a major-league manager, a landmark reached by only nine other men in the history of the game.

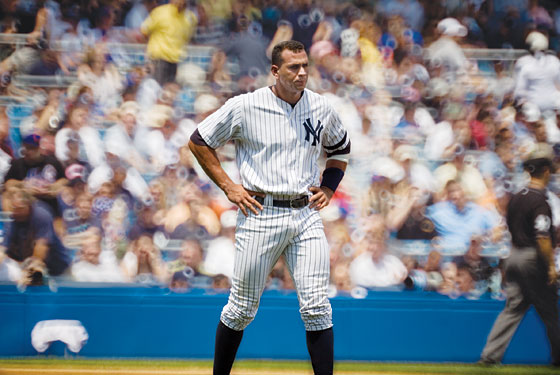

Torre nearly didn’t make it to this milestone. One week ago, with the Yankees wallowing in last place, 14½ games behind their eternal enemy, the Boston Red Sox, Torre was being battered daily with rumors that he was about to be fired. Tonight, as the manager shuffles into the shower, the root cause of so much of his angst—and the key to his salvation—emerges from the players’ private dressing room across the hallway, freshly moussed and lotioned and wearing an immaculate suit the color of a newly minted dollar coin. The golden boy is literally glowing.

Alex Rodriguez sealed tonight’s win with a majestic grand slam. Yet even this moment of triumph comes with an underlay of intrigue. This morning, a story with an anecdote intended to sabotage Torre appeared on Sports Illustrated’s Website, describing George Steinbrenner’s fury at Torre for criticizing A-Rod.

It has been a long road trip. Rodriguez nearly incited a brawl in Toronto, was besieged in Boston with questions about his friend the stripper, hit a game-winning homer against the Red Sox, then helped spark a winning streak in Chicago, and now, with microphones in his face, he’s trying to make sense of it all. “Everything about this year has been a little unusual, so I guess then, unusual is not unusual,” he says. “Joe is a Hall of Fame manager for so many reasons. For me personally, he’s done so much—”

He pauses. A-Rod is naturally, needily eager to talk, to make himself liked and understood. “And he’s dealt with so much that, uh—” He seems on the verge of something raw and honest—an apology? A tirade? Rodriguez fights back the impulse and retreats to boilerplate. “He’s just a pleasure to play for.” Then he flees for the safety of the team bus.

Joe Torre detected “something special” brewing at the end of that road trip, and he was right: The Yankees were going on a tear, fourteen wins in seventeen games. Better physical health, particularly among the starting pitchers, and a string of weak opponents certainly helped. Roger Clemens parachuted in at precisely the right moment. But Torre and Rodriguez have been central to the surge.

Torre again displayed his gift for calming the maelstrom: While the Yankees were still reeling, he called a team meeting and let players vent. Realizing that rumors of his firing were distracting the players—“He’s like a father to me,” Jorge Posada says, “I don’t want to play for nobody else”—he reminded them to concentrate on the things they could control: hitting, throwing, catching. He strengthened the defense, inserting Melky Cabrera full-time in center field and journeyman Miguel Cairo, Torre’s fourth choice, at first base. In April and May, as the team sagged with injuries and lousy play, Torre talked repeatedly about how the Yankees had lost their “identity.” In June, through a combination of design and desperation, the Yankees’ new identity suddenly resembles the team’s winning late-nineties profile, a mix of stars and grinders, pulling together in one direction.

Rodriguez’s contribution? He’s merely been a terror at the plate, piling up homers and RBIs with his deceptively effortless, brutally quick swing. In a perverse way, the exposure of Rodriguez’s escapades with a stripper seemed to have been good for him, at least on the field: He’s playing with a newfound focus and anger. “I just keep talking to him and just let him be who he is,” Torre says, “so he can relax enough to be the player he needs to be.”

In twelve tumultuous seasons as manager of the Yankees, Torre has deftly handled drunks, egomaniacs, self-righteous born-againers, blowhards, and a shy guitar-strumming center-fielder. But now the player he understands least is the one he needs the most. The care and feeding of A-Rod’s delicate psyche is the greatest challenge of Torre’s career. Torre, 66 years old and in the final year of his $19.2 million contract, wants one last World Series ring. Rodriguez, 31, desperately wants his first—and validation as a “true Yankee,” who’s about more than the gaudy numbers on his stats sheet and paycheck. What they have most in common, though, is that they’re two damaged men.

Joe Torre stands at the top of a cellar stairway in Marine Park, Brooklyn, looking at where his life nearly ended before it began. “This is where my father pushed my mother down the stairs,” he says quietly, “when he found out she was pregnant with me.”

His father already had four kids and didn’t want any more. Joe Sr. was a night-shift detective with the NYPD and an angry man. This wasn’t the first time he’d struck his wife, Margaret. Torre didn’t find out about the abuse until years later, when he was an adult himself. But like many kids from troubled marriages, Torre didn’t need things spelled out. He picked up the vibe plenty clearly, from his father’s banging on the wall when anyone accidentally woke him prematurely to the way the very air seemed to thicken when his father was in the house. By the time he was 12, if Joe arrived home from school to find his father’s Studebaker parked outside, he veered off, found a friend to hang out with, and stayed away until he was fairly certain Pop had left for the precinct.

Torre hasn’t lived in the house on Avenue T for more than 40 years. But after a recent season, he stopped by to talk about how his mother’s suffering inspired him to launch the Safe at Home Foundation for victims of domestic violence. Torre walks into the kitchen, stops in front of a drawer, and shudders a little bit. “This is where Pop kept his gun,” he says. One night, during a particularly vicious argument, Joe Sr. waved the gun at his wife. Torre’s sister Rae grabbed a knife to defend her mother. Joe, about 10 at the time, snatched it from her hand, slammed it on the kitchen table, and said, “Here!,” apparently defusing the tension.

Rae Torre still lives here and has never been married. His other sister, Marguerite, is a nun. Torre believes there’s a direct line between his mother’s pain and his sisters’ choices. His brother Rocco died of a heart attack in 1996. Frank Torre, who preceded Joe to the big leagues by four years, has long been his closest sibling. But the bravery Frank showed one day in 1952 made him a hero to the entire family. Frank assembled a family meeting and volunteered to kick his father out of the house.

That ended the immediate threat, but the damage to Joe Torre had been done. He says the failure of his first two marriages, and his strained relations with his children, was rooted in his inability to express his emotions, a self-preservation mechanism he’d learned as a kid—a realization he came to only in the mid-eighties, when Torre and his third wife, Ali, entered therapy. “Joe would shut down,” Ali says. “That was a big part of his personality, and the silence was just as bad as someone yelling. It was a big problem in our relationship.”

Another side effect of his unhappy childhood was that baseball became the core of Torre’s self-image. “Baseball was the one area where I could get some self-esteem,” Torre says. “Starting from when I played as a kid, if I didn’t do well, I felt inadequate. Maybe that’s what drove me to do well, because I knew that was one place I could find some common ground, to be able to talk to people. I had no self-esteem growing up. I was very shy, very nervous. Baseball was always my way through that. So I went a long time feeling I let people down if I hit into a double play to end the game or something. No matter how many hits I got or how well I’d been doing. That stood out more than the good times.”

They’ve put together two rare wins in a row, last night’s coming against the hated Red Sox. But the Yankees are still 12½ games out of first place, and the tension is always suffocating when the team is in Boston. But it’s still stunning that Joe Torre, the king of calm, is fuming.

Even more surprising is the proximate cause of his fury. This morning, Torre’s wife told him the early edition of the Daily News had a back-page photo of Alex Rodriguez with the banner headline TORRE TELLS A-ROD: SHUT UP! It’s the kind of provocative tabloid shorthand that Torre, in one of the most important aspects of his success, usually lets roll off his back. Not today. He’s threatening a media boycott, claiming he’s been misrepresented.

As always with the Yankees, there are a dozen subplots. Torre has been cranky with the Daily News since last October, when the paper loudly proclaimed him fired. Three days ago, in Toronto, Rodriguez had shouted, “Ha!” while passing a Blue Jays infielder, an amateurish—and successful—attempt to distract the third baseman from catching a pop-up. Immediately after the game, Torre characteristically deflected questions and dampened the controversy. Two days later in Boston, though, Torre reversed himself and criticized Rodriguez. No doubt Torre was speaking honestly when he said Rodriguez’s stunt was “inappropriate.” But the larger context was that Torre seemed to recognize that many of his other, well-behaved players had grown weary of the constant A-Rod sideshow.

“Joe still doesn’t completely understand A-Rod,” says Tim McCarver, the catcher turned broadcaster who has been a close friend of Torre’s since they played together on the 1969 St. Louis Cardinals. “Joe considers A-Rod a very complex personality. He’s meticulous, he’s eccentric. He’s almost got the personality of a pitcher. You expect pitchers to be peculiar people.”

Torre’s anxiety can always be measured indirectly by how quickly he burns out his bullpen, and this year he’s been particularly jumpy, even using Andy Pettitte twice in relief. He’s also continued to shuffle his weak hand at first base, instead of settling for stability and competence with Cairo. But the outburst provoked by the Daily News headline was a rare instance of Torre showing the pressure overtly.

The intensity—and the true source—of that pressure didn’t become clear until five days later, in Chicago. That’s when the SI.com item appeared, describing how Steinbrenner was livid at Torre for spanking A-Rod in public. Torre has plenty of experience with the Boss’s rages; the fact that the phone call was leaked was more interesting, and upsetting. Not only did it poke at Torre’s fragile bond with Rodriguez, but it showed that someone with connections deep inside the Yankees hierarchy was trying to undermine Torre. When an Associated Press reporter who looks about 13 years old raises the item with Torre, the manager glares, watching the kid squirm. “Do you have a comment?” the reporter asks. “No,” Torre snaps.

“Is the report accurate?”

“If I gave you a yes or no on that one,” Torre says with a smirk, “it would be a comment. See, you gave me the option of commenting, and I said no.” Twenty chilly seconds of silence pass before Torre changes the subject to the weather.

Friends like Mel Stottlemyre, Torre’s pitching coach for ten seasons, eventually tired of the pettiness of life with the Yankees and quit. Torre willingly continues to endure the humiliations, and when necessary deploys the kind of cold-blooded political survival skills that belie his image as Saint Joe. “His friends say, ‘I wouldn’t put up with that shit,’ ” McCarver says. “But it took so long for Joe to be looked upon as a success as a manager. He gets to the Yankees and finally he’s got an owner who’s willing to pay the money and get him the players he needs. And once you’ve tasted that success, it’s hard to shuck it aside and say, ‘Oh, well, now I’ve achieved everything.’ And people underestimate how competitive he is.”

Ali Torre began dating Joe when he was managing the Mets. But it wasn’t until he was fired by the Braves, in 1984, that she realized the depth of the hole in his emotions. “There was a confusion in Joe,” she says. “He didn’t really feel loved. He went through a period where he lost his identity. His whole identity was as a baseball player, and now he was no longer in uniform. I sensed that he felt that people didn’t love him unless he was a baseball player.” Ali steered Joe into therapy. Days after he’d been hired to manage the Yankees, he was weeping in a roomful of strangers as he talked about his father.

The autograph gnats are swarming behind restraining ropes on the sidewalk outside the Chicago Westin hotel. Men, women, children, all without enough to do in their lives, linger outside the Yankees’ hotel day and night. The action really heats up when the team buses arrive mid-afternoon to take the players and coaches to the ballpark.

The Sharpie-waving horde misses a woman stepping out of a black Escalade halfway down the block. Cynthia Rodriguez wears dark sunglasses, and her curly-haired 2-year-old daughter, who is sleeping, is slung over Mom’s shoulder. Mrs. A-Rod is flanked by two security guards as she ducks into a side entrance to the hotel.

It is six days since her husband appeared on the front page of the Post with the Other Woman. The next day, Cynthia Rodriguez flew to Boston, where the Yankees were playing the Red Sox, and went strolling through the streets with her husband, smiling as if nothing were wrong. In Chicago, A-Rod and his wife parade down Michigan Avenue, the city’s glossiest shopping strip, pushing their daughter in a stroller and eating lunch at an outdoor café, trailed by paparazzi. It all seems transparently staged for public consumption, but A-Rod ends the excursion by cursing at the photographers, “You had enough? I’m out with my family. Now get the fuck out of my way.” (Torre makes the same stroll unnoticed, even when he buys a suit in the Zegna boutique.)

Everyone wants A-Rod. Another afternoon in Chicago, the day of baseball’s amateur draft, Rodriguez is reminiscing about his entry into pro ball. Major League Baseball’s arcane eligibility rules at the time put an amateur player off-limits as soon as he attended a college class. Months of negotiations with the Seattle Mariners had stalled and he was carrying an armful of books across campus toward his first class at the University of Miami. Then, a Mariners executive who had literally been hiding in the bushes intercepted A-Rod with a sweetened offer.

Unimaginable riches weren’t far behind. The Texas Rangers lured A-Rod with a ten-year, $252 million contract, but it soon became an albatross and led to his 2004 trade to the Yankees, one of the few teams that could easily swallow such an expense. Rodriguez, though, has had a turbulent time in New York. During his first season with the Yankees, after a jittery Rodriguez rushed a throw from third base, Torre intercepted him in the dugout. “We start today,” the manager told A-Rod calmly—the beginning of a long seminar in ignoring impossible expectations and setting aside any failures to concentrate on the moment.

“He tried to take on too much responsibility himself—that’s the only thing I’ve brought up,” says Torre of A-Rod. “We don’t need one guy to carry the whole thing.”

Rodriguez’s father left the family when Alex was 9 years old. As much pain as that split inflicted on him, the young Rodriguez was at least equally wounded by a seemingly positive force—excessive praise. He was stroked and coddled from the moment his baseball gifts first emerged, and his early years as a pro reinforced the worship. His agent, Scott Boras, is a master at buffing his clients’ egos. So A-Rod’s entry into New York, that cauldron of what-have-you-done-for-me-lately, was extremely jarring. “The problems he had at first were more or less trying to get used to the limelight in New York when statistics are one thing, but the ability to do something every single day is more necessary than it is with a club that is not going to contend,” Torre says. “He tried to take on too much responsibility himself. That’s the only thing I’ve brought up to him, that there’s enough to go around here, we’ve got enough players who have that leadership ability. We don’t need one guy to carry the whole thing.”

Last fall, when the playoffs began, Rodriguez slumped. Torre shifted him lower in the batting order, trying to reduce the pressure—but only increased it. The manager has been continually surprised at his superstar’s thin skin and insecurity. “Roger [Clemens] got toughened up basically because he’s been booed a lot of places,” Torre says. “Alex hadn’t gone through that. And he’s always been the spokesperson for the team, wherever he played. All of a sudden, he comes to the Yankees and he looks around and everybody is eye level with him, where he’s always had people that weren’t up to his level. It took some adjusting.” It isn’t done yet. For his monster individual statistics and polished persona, A-Rod was rewarded with a record-breaking contract by the lowly Rangers. But those aren’t the qualities that New York values, and it has left Rodriguez confused. He’s nowhere near as good as Torre at cultivating the press, so it’s probably too late for him to win over the city’s heart. But he may finally be earning its respect.

It is Father’s Day, and the patriarchal psychodrama at Yankee Stadium is so tangled that Venn diagrams should be issued with tonight’s programs. To promote early detection of prostate cancer, Major League Baseball asks everyone to stand for a sixth-inning stretch (one in six men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer—get it?). Beside the Yankees dugout stands Rudy Giuliani, prostate-cancer survivor and presidential candidate; beside him is his third wife, Judi Nathan. Rudy’s son, Andrew, is in the ballpark, but the seat beside Judi stays empty all night. Giuliani, who had some father issues himself, wears a pale-blue golf shirt that matches the pale-blue prostate-cancer-awareness wristbands worn by Torre and the players; the wristbands have DAD printed on them in large navy letters. Rodriguez, who wears nothing out of place or by accident, has a dark sweatband covering all but a pale-blue sliver of the DAD band.

Over the years Torre has grown into a father figure not just for the team but also the city, sipping green tea and issuing warm but stern advice. At home, he’s become the man his own father never was. And now Torre is witnessing the slow fade of Steinbrenner, the man who in many ways has been father to the greatest success of his managerial life.

The core of Torre’s success hasn’t been in-game strategy but his genius at parenting his physically gifted, emotionally stunted children in pinstripes. Rodriguez hasn’t so much rejected Torre’s paternal touch as he’s been confused about how to accept it, especially while tiptoeing around Torre’s favorite surrogate son, Jeter. The dominant figure in A-Rod’s life and brain, ever since he was a prodigal 17-year-old No. 1 draft pick, has been Boras. It was Boras who promoted Rodriguez as this generation’s greatest player, even before A-Rod proved it on the field, and who sold Rodriguez on leaving a happy situation in Seattle for a whopping payday in Texas—and who crafted the contract’s out clause, effective at the end of this season, that could make A-Rod even richer.

The notion that he has one foot out the door fuels the feeling that Rodriguez isn’t fully committed to the greater Yankees cause, at least emotionally. Lately, though, Rodriguez’s searing play shows signs of a breakthrough, or maybe a surrender. Whatever is happening in his home life—or perhaps because of what’s happening in his home life—A-Rod looks blissfully unconflicted in the batter’s box. Tonight he hits another gargantuan homer. Later, on a mere double, Rodriguez smacks a ball even harder, into the left-center gap, as the red-hot Yankees demolish the Mets.

Last season, when his hitting touch disappeared and the fans booed, A-Rod went to pieces and became such a mental mess that his batting troubles infected his ability to field easy ground balls. What’s different now? Why, in the face of seemingly worse stress, has A-Rod shrugged it off and gone back to playing as if he’s a bargain at $252 million?

“Well, he’s lost ten or twelve pounds, which makes him quicker at third base,” Torre says after the game, attempting a rational analysis. “But how his mind is different from last year, why he hasn’t let it affect him…” Torre shrugs, his words drifting off. “I don’t know what you can say it is.

“I think we’re all human, and it comes to a point where you all of a sudden stop having to deal with all that stuff and just—you hide,” he continues. “You hide on the field. That’s something we’ve all done from time to time as players. Whether it’s what Alex was dealing with or something else, there’s always something that you have to try to block out so you can do your thing.”

A few steps away, in front of his locker, Rodriguez is lit by TV-camera strobes and surrounded by notebooks. “Nothing means anything until our next game,” he says.

He’s dressed in a tight-fitting T-shirt the color of Georgia clay. It’s flattering to his sculpted chest and biceps—except for the sequins on the left sleeve, an oddly fey touch. A-Rod’s collar is frayed. Not in a phony “distressed” designer way. It’s just worn, the kind of look you’d expect on a knockaround guy from Brooklyn, not a diva from Miami. Dr. Torre’s treatment is working. At least until the next crisis.