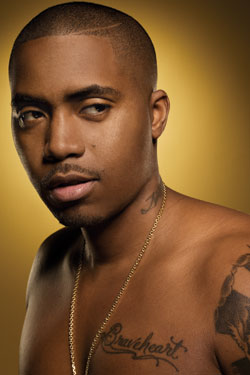

It’s Friday at four in the afternoon, and Nas, eyes half-lidded, is trying to remember the names of the producers who provided the beats on his new record. He’s slouched in a chair behind the mixing board at Electric Lady studio on West 8th Street. Green pellets of weed are scattered on a cabinet behind him. A big guy named Zaire, a childhood friend, is on a couch in the corner, dozing, with his arms folded across his chest. Colored waveforms scroll across an engineer’s laptop, and the day’s work leaks out in tinny miniature from his headphones.

He’s got one: “Stic.maaaan,” Nas says in a reverential drawl, referring to one-half of the hip-hop group Dead Prez. “I’ve always been a fan of their work,” he starts, but then trails off and rests his head in his hands, thinking.

He turns to his assistant. “Yo, who’s on the album?”

His assistant obliges.

That these producers don’t spring to Nas’s lips is, perhaps, not surprising: He has made his reputation not on hook-laden pop-rap and club bangers, but on hip-hop that sounds best in headphones, in which it’s possible to keep up with the flow of his detailed, controlled verses. He consciously chooses beats that are light on hooks, he says, so as not to distract from the lyrics. It’s a move that has brought him criticism—the weak-beats gripe—but while his beat selection has kept him from the top of the pop charts, it has also protected him from its whims. The rapper has enjoyed an unusually long career.

To say that Nas’s new album is one of the most anticipated of the summer is true, but it misses the point—every Nas album is highly anticipated, because no rapper is held to as high a standard. When a Nas record is about to drop, hip-hop fans cross their fingers and wonder: Will he change hip-hop forever, again? Will the new record be as good as Illmatic?

Released in 1994, when Nas was 20, Illmatic was a prodigious debut. No other rap debut, and few rap albums at all, are as lauded. It’s hard to quantify the album’s achievement precisely, except to say that rapping is a craft, and Nas was the first to discover how to do it right. Rap has two components—beats and rhymes. On Illmatic, the beats were mostly good, sometimes great; and there had been virtuoso emcees before Nas who’d moved the stylized rhythms of early groups like N.W.A toward the conversational. But no one had ever sounded as natural as Nas. “One Love,” which takes the form of a monologue to an incarcerated friend, exploits poetic devices like enjambment so subtly that it works as prose. Every rapper who hopes to be taken seriously—from Kanye West to the Game—must grapple with Nas’s discovery.

Discoveries only occur once. Still, with every new album, fans begin to fantasize about another Illmatic, and anticipation has run particularly high since last December, when it was revealed that Nas had decided to title his record Nigger. Not N, or Nigga, but the epithet in full. Giving an album a controversial title is a familiar buzz generator, but it seems to have worked: The outcry he’s ginned up is the stuff that blogs are made for, and even observers who didn’t know Nas from Nelly found themselves in possession of fervently held opinions. The album, which like most hip-hop releases has been delayed a half-dozen times (another surefire trick), is now set to drop July 15.

Nas wheels his chair over to the cabinet and sprinkles some weed into the paper cradled between two fingers. A yellow legal pad, across which are written lyrics for the new album, lies nearby. His script is whorled and glyphic, and is mostly uncorrected. “I think about what I want it to sound like,” he says. “No words come to mind really. I used to be the kind of guy that took notes in my head or my pager. But I kind of just wing it now. I like to be surprised by what comes out.”

He licks the glue strip and sparks up a tidy joint.

When he was young, he says, he used to take a tape recorder out into the hallway of the Queensbridge projects and rhyme over it to pass the time. “I’d just freestyle and have fun,” he says. “And if it made enough sense, I could play it to a group of people and they’d like it.”

Back then, rap was still largely confined to certain New York neighborhoods like Queensbridge. It was a tight community, and rap was a game. “Everybody who was doing music back then,” he says, “just wanted to keep on doing music, making beats, trying to make records. Anybody would hook up with anybody else.” That openness led Nas to reach out to a producer called Large Professor who, though still in high school, was no less legendary for it: He’d already provided beats for Eric B. & Rakim, the duo who released a string of immortal records beginning in 1986. These days, of course, a figure like Large Professor wouldn’t even reply to an e-mail from an unsigned youngster, much less provide him with three classic beats for his debut.

But times were different. “It didn’t matter that Large Professor had a record out and I didn’t,” Nas says. “Didn’t matter who it was, as long as you were working. He didn’t even know me, but he came down [to the studio] anyway. He was probably just bored that day. But I got in there and did my thing.”

Nas made such an impression on the Professor that he was introduced to Eric B. & Rakim—“the kings of the world,” as Nas remembers. He soon got to know other star producers, and when the time came to make Illmatic, Nas did something that hadn’t been done before: Instead of relying on just one production team, he hand-picked multiple producers. It’s a practice that is now de rigueur in mainstream rap. (This assembly-line approach is not necessarily good for the art; it’s the only ambiguous component of Illmatic’s legacy.)

In his recent albums, Nas has grown increasingly focused on shoring up the vitality that hip-hop lost when it became a global business, and recovering the memories of the days when hip-hop was synonymous with New York. “The Tunnel was the club for a moment,” he says, referring to the mid-nineties, when the historic nightclub occupied a vast space on Eleventh Avenue in Chelsea. “Whatever song was out at the time, the whole city was part of it. All the movements that were around, from Wu-Tang to Bad Boy—when their records came on from that spot, you’d see that section go crazy. And you’d know those guys were from Staten Island and Wu-Tang fans. Then when the Mobb Deep records came on, you’d see a bunch of dudes going crazy—that’s Queens. You’d see Biggie come on—that’s Brooklyn.”

Nas’s preoccupation with hip-hop history—in one two-and-a-half-minute track from 2006’s eloquent Hip Hop Is Dead, he name-checks 56 largely forgotten rap pioneers—has made him a sometimes awkward fit in today’s sleek industry. In a personality-driven genre, Nas isn’t a personality. His public image is vague; one gets an impression of intelligence and integrity, but nothing specific. He was never the dead-eyed tough who rapped about selling crack—he was the street-smart kid who rapped about friends who sold crack (“Represent”). He’s not a gangster who raps about shooting people—he’s a thug who thanks God people prevented him from doing so (“Get Down”).

But Nas thinks that rappers can get mired in tropes and put-on identities, afraid to change the formula that brought them success. To sell records and remain viable as a business, they highlight one titillating aspect of their personality and paper over the rest. (Think of 50 Cent, who came to notoriety on Tourette’s-style reminders that he’d once been shot nine times.)

“A lot of rappers aren’t really who they say they are,” he says. “It’s a gimmick. Real men have children!” he exclaims in mock incredulity. (Nas has a daughter from a previous relationship.) “We have nieces, nephews, little cousins, little sisters.” In the track “I Can” from 2002’s excellent God’s Son, he cautioned young girls about the dangers of HIV. On “The Cross,” he spits a rhyme that zigs in a direction that’s very familiar to gangster rap—“And I don’t need much but a Dutch / A bitch to fuck / A six, a truck / Some guns to bust”— before zagging: “I wish it was that simple.”

Nas hasn’t just been poetic and self-effacing. In 2001, he and his Brooklyn rival, Jay-Z, engaged in one of the highest-profile rap battles to date. (The rivalry continued, to their mutual benefit, until the end of 2005, after which Nas signed to Def Jam Records, where Jay-Z was then CEO.)

And once on Def Jam, Nas, it seemed, had succumbed to the advice of marketers: He and his wife, the R&B–neo-soul singer Kelis, signed up to make a reality show for MTV. A clip available online previews what might have been if MTV hadn’t pulled the plug: Kelis politely greets a bodyguard on the tour bus—“Hi! How are you? I’m good”—complains about cramps, then sniffs her husband’s armpits. Nas helps someone off-camera find something in a duffel bag.

Nas now realizes it would have been a snooze. “We shot two episodes,” he says, and laughs. “Me and the wife didn’t get excited. MTV agreed with us. I mean, leave the guys who are supposed to be on TV to be on TV.”

Of course, the controversy over his new record’s title almost seems like it was scripted for reality television. Jesse Jackson accused Nas of behaving dishonorably for trafficking in the forbidden, prompting Nas to reply that Jackson had, in effect, called him a nigger by assuming he had nothing substantive to say and was merely scandal-mongering. Al Sharpton said his piece, as did the NAACP, Fox News, and 50 Cent (“That’s a stupid name”). A slew of rappers like Lupe Fiasco, GZA, and Akon came out in support of Nas. His label, Def Jam, did too, for a while. But on May 19 Nas announced that the name had been removed.

The album is now untitled, but bears an image of Nas’s back covered in welts that form the letter N. He’s not surprised by all the free publicity, but he also believes that the fault lines in the black community’s reaction reflect one of the themes he explores on the album: the broken relationship between the older generation of African-Americans, who fought against the word, and the younger one, who use it casually.

“In the black community, the elders and the youth don’t know each other.” The older generation, he says, “made it through the storm [of the civil-rights movement]. We’re still in it.”

When he gets older, Nas says, “I’m never going to turn my back on the younger generation, no matter how crazy and insane they are, and how many drugs they sell. I’m never going to blame them for it. I’m never going to come down on them. I’m never going to talk from a position of superiority. I’m going to have my opinion, but I’m never going to do how the elders do, like they own the civil-rights struggle. Thank God for the people who came before us,” he says, “but they can’t tell me nothing.”