Anarchy’s for sale here. You can buy it on the street for $49.99, plus tax, in the form of studded belts, scuffed leather jackets, fingerless gloves, and Sex Pistols action figures. But that didn’t stop Suvy, who is 18 years old, from arriving two months ago, straight out of juvie with a backpack and spiked hair—a simple decision, really, for a kid who thought of himself as a punk. Such is the pull of the St. Marks mythology.

It’s late afternoon, and though he’s been drinking since he woke up around noon in a squat in Brooklyn, Suvy now plots his next beer. He’s sprawled with some of the usual guys on the sidewalk next to the abandoned falafel shop on St. Marks Place, a piece of prime real estate if you hang out on the street. Suvy squatted inside for a while, until a man came in one night, found him in his sleeping bag, naked and wasted, and kicked him out. “I guess I didn’t pay my rent.”

You can’t get away with anything around here anymore. “St. Marks used to be, like, a punk block,” Suvy says. “It used to be overrun with punks. Now it’s like fucking BBQ Chicken and fucking Chipotle, whatever that fucking store is.” John Varvatos has taken over CBGB. Trash & Vaudeville peddles overpriced punk trinkets to tourists. That very day in Tompkins Square Park they’ve set up a big stage, and there’s an infestation of tweens in dance uniforms and glitter paint and families with juice bottles preening on the benches—a far cry from the park’s glory days as a tent village for the city’s lost and broken. “Everyone used to live there,” Suvy says. “But then the cops came and bulldozed it, and now it’s pretty much just a cop hot spot.”

The halcyon days of the punk movement were over before Suvy was born, of course, but each year as the weather warms, hundreds of kids like him descend on St. Marks. They’ve learned the names of the bands. They’ve memorized the lyrics. They’ve carefully crafted the look, gotten the piercings, the tattoos. They come hoping to tap into a scene that no longer exists, but in the process they’ve accidentally created a new one, an ersatz summer camp of misfits and would-be rebels. Some come from the boroughs or the suburbs; for others, it’s a stop on a migratory circuit that includes Portland, Oregon, and New Orleans. Some are fleeing broken families, others just looking for adventure. The common denominator seems to be not family, not class, not race, but merely a highly evolved sense of teenage angst, for which punk provides a ready-made, if recycled, outlet.

There are glam punks and goth punks and skater punks and ska punks. Suvy’s squatting partners Greg and Jamie are crustie punks—that’s punk with a dash of hippie. Jamie’s girlfriend, Jazmin, is a metal punk. Their friend Miquel is a hobo. And Eric is a rockabilly punk who combs his green hair back fifties style.

Suvy calls himself a gutter punk—the closest thing, he says, to the original version. He was kicked out of his home in Philly about a year ago because, he says, “my parents are metal heads and they hate me.” He dropped out of school, couch-surfed for a while, then got picked up for breaking into houses. After seven months in juvie, he had only one plan: getting himself to St. Marks Place. “I heard about St. Marks in a Casualties song,” he says, “so I’m like, ‘Wait a second, I want to hang out there.’ ” That’s what he was doing when he met Greg, who showed him places to squat. He sometimes sleeps in an industrial building in Williamsburg, sometimes in the park, sometimes under a bridge by the East River, sometimes even with women who warm to his cherubic features and haphazard charisma. A few more years of living this life and he won’t be so pretty.

“Hey, what’s up?” he calls out to a girl walking past in plaid pants and a Casualties shirt. She pauses long enough for him to know he might have a chance. “You’re really hot. Come over here.”

Up close, she’s not as cool as she initially seemed. She tells Suvy that she’s a freshman at a high school in Brooklyn, which means first of all that she goes to school and second that she probably lives with her parents. Then there’s the striped glove she’s wearing on one hand, which besides being impeccably clean is exactly the type of merchandise you purchase if you want to look punk. Still, she’s cute, voluptuous and freckled, and Suvy aims to impress.

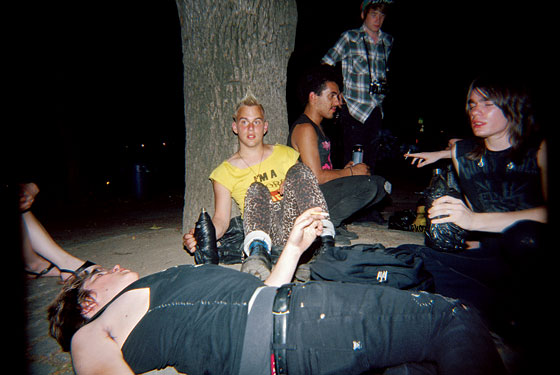

Right: Greg, left, showed Suvy good places to squat. Photo: Rona Yefman

“You guys should have been here the first day I came to New York, like right after I got out of being locked up,” he drawls, looking over to make sure she’s listening. “My alcohol tolerance was so low I’d be passed out every day, like drunk in the middle of the sidewalk. I’d be yelling at people, like, ‘Fuck you!’ ”

The girl, Mariya, giggles and twists a strand of streaked hair around her finger.

“Fuck you!” Suvy yells, inspired, at an unremarkable hipster walking past. “I fucking hate yuppies.”

“Yuppies are assholes,” Miquel agrees.

“This is St. Marks. They should go away.”

“They have no culture. They have no history. They’re like plastic.”

“Of course, I don’t discriminate,” Suvy reasons, grinning at Mariya. “I hate everybody besides punks.”

Punk, says Suvy, is “the only view that makes sense to me.” Work is for yuppies. Rent is for yuppies. Shelter is a basic human right. The government is bullshit. Corporations are bullshit. He “fucks capitalism” by pissing in the corner of the Dunkin’ Donuts.

“No one has a right to tell anyone else what to do,” Greg says. “Like, it’s your life, you should be in control of it. I don’t pay for anything—just drugs. They don’t tax drug dealers.”

“Hey, you guys want to see that punk show?” Suvy suddenly asks. Rumors have been circulating of a free show that night in Bushwick. The question is how to get sufficiently blasted to appreciate it. Greg thinks he knows where they can get ecstasy for $15 a pill, but who has that kind of money? Eric agrees with Suvy that Elmer’s glue or rubber cement might be the best solution, if they can find some.

“You should come to the show,” Suvy tells Mariya as she nestles next to him.

Make no mistake: A house punk, who can go home at night, is not a punk punk. “MySpace punks,” Jazmin calls them. “Like, ‘Oh, Mom, I want a pair of bondage pants!’”

She grows suddenly shy, peeking out at him from behind her bangs. “I sneaked out,” she admits. “I have to get home.”

“Man.” Suvy looks crestfallen. “The show’s free.” He pours from a brown-bagged Colt 45 into a McDonald’s cup, and she downs it in one gulp before writing her number on his arm in black Magic Marker. When she leaves, she gives him her glove and a quick kiss.

“Mariya’s a hottie,” Miquel comments, watching her go.

“She’s a mall goth,” Jazmin tells Suvy, disapprovingly. “That’s so lame.”

Suvy glares at her. “I don’t care, dude. I still like her.”

“You like her for who she is, right?” Jazmin asks, rolling her eyes.

Alex and Toast are waiting for them on the steps outside Saint Mark’s Church on 10th Street and Second Avenue. Alex goes to college, but during summer break he comes down to the city from Westchester to get stoned. Toast lives in Queens and wears Armani glasses and calls himself Toast “because I’m always toasted.” They’re both house punks, meaning that they have homes they sleep in every night and at least some money, and for this the squatter kids—even the ones from the city who can go home when it rains or if they need a good meal—find them both slightly suspicious and also intermittently useful for buying things like beer and weed. But make no mistake: A house punk is not a punk punk. They water down what’s left of the scene.

“Now it’s a bunch of fucking kids who are like, ‘Ooh, I’m punk, I’m punk!’ ” says Greg. “They think they know a few bands and they think that gives them the right to call themselves whatever they want and they fucking run around and then they go back home to their white, suburban comfort zone.”

“MySpace punks,” Jazmin calls them. “Like, ‘Oh, Mom, I want a pair of bondage pants!’ ”

The squatter kids mostly get by with spanging (spare-changing), especially Greg, who’s disconcertingly thin. Suvy picks up cash from the tourists who come to St. Marks hoping to see someone just like him and who pay, a dollar a shot, for the privilege of taking his picture to show the folks back home: Look, punk is still alive!

Tonight they and their limited funds haven’t managed to scrounge up anything stronger than alcohol, but Toast has pot, which he’s packed into a one-hitter—a small pipe painted to look like a cigarette—and there’s a chance that he’ll share. He holds the pipe covertly as the others gather around, lounging on the clammy steps. The churchyard usually makes a good place to hang out—far back from the street, enclosed by a fence. But tonight proves unlucky. They had barely settled in when two stocky cops amble out of the darkness and pull Toast to his feet.

“You got any more weed on you?” the younger one asks, cinching a pair of handcuffs.

Right: Suvy playing in the rain on St. Marks Place. Photo: Rona Yefman

“Um, I don’t know.” Toast’s voice is tiny. Unlike some of the squatter kids, he’s never been arrested.

“You got any I.D.?”

“Yes, sir. In my pocket.”

The young cop rummages in Toast’s pants, while the other checks out his one-hitter for debris.

“Let’s go. You’re coming with us. Gonna spend the night in jail, all right?”

Alex asks if he can follow his friend to the station, but they cut him off. “What, you want to get arrested, too?”

The cops lead Toast away. For a few seconds, no one speaks. Then Miquel whistles through his teeth. “Dude, that was fucking nuts.”

“What the fuck was that?” Eric asks.

“Dude, we can’t stay around here,” Suvy says. “They know we’re all fucked up.” If there’s one thing Suvy hates more than anything else, it’s cops. In addition to the anarchy sign tattooed at the base of his thumb and the inverted cross on his middle finger, he has ACAB inked between his knuckles. All. Cops. Are. Bastards.

“Let’s just go,” he says. “Let’s go to this show. Where is this show?”

“Um,” Alex mutters. “I think the guy who knew just got arrested.”

Turns out the show is at a place called the Wreck Room in Bushwick, which wouldn’t necessarily be worth the subway ride to get there if it didn’t have the reputation as a decent spot to hear punk.

“Let’s go, let’s go, let’s go!” Suvy chants. Music is important to him; it’s what drew him to the punk scene in the first place. “Like, when I was a little kid, I had so much anger and shit,” he says. “I listened to a whole bunch of different music, but the only thing that really touched me was punk. It’s a good way to, like, express your anger.”

The thought of this concert gets him so worked up that he drops his beer. As the others egg him on, he kneels down to slurp it off the street.

In the L station at 14th Street and First Avenue, they wait until they can hear the train coming before jumping the turnstile, a trick to keep the attendant from having time to stop them. Eric, Miquel, and Alex squeeze into a car just in time, but the door closes on Suvy, Jamie, Greg, and Jazmin. Luckily, the guy on duty isn’t paying attention.

They reunite in Brooklyn, clambering out of the subway and back into the night, a ragtag parade of dyed hair and patches, ripped pants and piercings. No one knows exactly where the bar is, so they try first one street, then another, filing quickly past the low-slung warehouses, the gloomy garages. The night has grown blustery and rain darkens the deserted pavement. “Where the fuck are we?” Jazmin asks to a round of silence.

Finally, they see a glow of light in the distance: a storefront with fluorescent beer signs illuminating the window. From outside, you can hear the muffled pulse of a heavy drumbeat and the hum of a crowd. Jazmin grabs Jamie’s hand excitedly. Suvy smoothes up his Mohawk in anticipation.

Once inside, though, their faces fall. The front room is riddled with hipsters, the current incarnation of yuppie scum, lined up at the bar. In the small back room where the band is playing, there are only a handful of people, not nearly enough for a mosh pit. And even if there were, the music could hardly inspire any thrashing about. The band is a joke—a bunch of paunchy guys in their forties flopping around on a plywood stage. “I used to be able to jump higher, but I’ve put on some weight over the years,” the lead singer admits between songs.

This is not punk.

Suvy is disgusted. “I want to die young. Once I hit like 30, I want to start being really self-destructive and just see what happens. Like ride around in cars really fast and do crazy stuff—even though I already do that now, so I can’t really say I’m going to do it.”

The rest of them just stand there, dumbfounded, or plop down in the folding chairs that border the walls.

“Eric, you lose cool points for taking me here,” says Greg.

“Fuck this shit,” Suvy adds with disdain.

After five minutes, they decide that there’s no point in sticking around. They head back to St. Marks. It may not be punk anymore either, but as Suvy says, “It’s not gonna help it just by leaving, abandoning it, you know? You’d be just as bad as these yuppies coming in and making stores.” At least it’s got people, like them, trying to be punk. At least it’s got history, the faint residue of New York in the eighties. “And New York in the eighties,” Suvy says with authority, “was insane.”