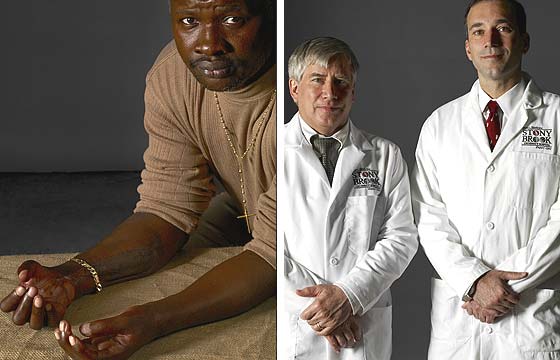

Patient: Arcenio Matias, 49, plastics-factory supervisor

Doctors: Alexander Dagum, plastic surgeon, and Lawrence Hurst, orthopedic surgeon, Stony Brook University Hospital

1. Conductor, 89, With Heart Problems, Too Old and Sick for Surgery2. Firefighter Separates Spine From Skull3. Taxi Driver Survives Testicular Cancer4. Baby With Severe Back and Rib Problems5. College Student Going Blind in Both Eyes6. Factory Worker Loses Hands7. Hockey-Mad 5-Year-Old Has Potentially Fatal Tumor8. Woman Carrying Triplets Has Torn Aorta9. Woman Needs Heart and Lung Transplant10. Hip-Replacement Complications May Cost a Woman Her Leg11. Four Siblings With Potentially Fatal Kidney Disease

Matias: I can’t really talk about the factory accident, because my lawyers don’t want me to. But I thought the machine was off, and then I saw the hands on the floor … and the blood. Someone put my hands on ice and wrapped my arms in a tourniquet, and I waited for the ambulance for 40 minutes. Then the helicopter took me to Stony Brook. I didn’t think about the pain—I just thought that my hands were gone, that I would never get them back.

Dagum: When Arcenio was wheeled into the surgery suite, I thought, Oh, my gosh, both hands. But I also thought reattachment would be possible if we worked quickly. We basically had a twelve-hour window to reattach both hands—that’s how long it would take before the hands died.

Hurst: When I joined Dr. Dagum in the OR, Arcenio was on the operating table, the amputated parts on the back table. Dr. Dagum was working on the left stump, so I started in on the right hand and began cleaning the parts and debriding the tissue, meaning I was cutting away at any area that was damaged to the point of being dead. We also had to make the bones in the wrist a bit shorter so that later on, when we reconnected the hand to the stump, the trimmed vessels would be long enough to reach where they had to go.

Dagum: We worked simultaneously to save time. I prepared the tendons, arteries, veins, and bones for reattachment.

Hurst: Once everything was ready for reattachment, we inserted pins through the bones of the hands and drilled them into the bones of the wrist and forearm, securing the hands back onto the arms. Then we worked under the microscope to reattach the veins, arteries, and nerves. About five hours after we started operating, we saw that blood was flowing—the hands were pink and alive.

Dagum: We sutured the arteries, veins, and nerves together. He had a slightly more serious injury on the right side, and I performed a vein graft on one of his arteries and repaired the fracture to the bone.

I didn’t think about the pain—I just thought that my hands were gone, that I would never get them back.

Matias: When I woke up in the recovery room, I saw my family coming to me, and when I looked at my hands, I saw my hands back. I couldn’t feel them, but I never thought I’d have them again, so I was happy.

Dagum: Many times you can lose replants to infection and vein blockage, but in the days following Arcenio’s surgery, blood never failed to flow. It’s very rare to see bilateral reattachments, but everything went Arcenio’s way.

Matias: I was in the hospital for one month and one day, and I started feeling my hands little by little. I do therapy every day. I try to do things on my own—I use pants with an elastic band so I can dress myself.

Dagum: He’s never going to have fine motor function, but he can feel hot and cold, feed himself, dress himself, use the phone—and it’s much better psychologically for a patient to have his own hands instead of prosthetics.

Matias: It’s the little things that make me happy now, like showering by myself and being able to brush my teeth. Just being able to put my shoes on—it makes me feel independent. The real happiness of my life is my 5-year-old twin daughters. I can play with them and hug them with my own arms and hands. Next: Five-Year-Old Has Potentially Fatal Tumor