THE KEY

Dr. Lung … …Pulmonologist

Dr. Heart1 … . .Cardiologist

Dr. Heart2 … . .Cardiologist

Dr. Virus … … Infectious Diseases

Dr. Baby … … .OB/GYN

How should a person choose a doctor?

Dr. Heart1: Looking at where a doctor went to medical school is a good place to start. You shouldn’t necessarily knock someone off who comes from a foreign medical school or an unknown school in the Midwest, but top-tier schools have already done the legwork of weeding out people. It’s like having a personal shopper give you the top ten suits to choose from—instead of having to go to the department store and look at them all yourself.

Dr. Virus: I think it’s the same as choosing a car mechanic. You have a person who does your taxes, and you make a decision about which person to hire. Maybe you have a lawyer as well. You deal with professionals who know more than you in all walks of life, and you somehow learn how to find out who’s full of shit and who’s not.

This is a matter of life and death. You’re saying it’s like choosing an accountant?

Dr. Virus: Well, yeah, I am saying that. I think better doctors are typically at better hospitals. If I were to pick a financial planner, I wouldn’t go to Joe Shmoe’s down the street; I’d go to Smith Barney, Goldman Sachs, whatever. Start with a brand name and find someone you connect with.

So can I assume that if I go to a major teaching hospital, I’ll have a good doctor?

Dr. Virus: No, but your statistical risk of turning up a clown is much lower.

Dr. Baby: How anyone who lives an hour away from Manhattan is going to Guardian Angel Hospital in New Jersey or some 40-bed schlock house in Queens is beyond me. If it’s “Manhattan scares me” or “I don’t want to go to a big hospital,” that’s your first mistake. If you’re not sure of a doctor, at least go where there are residents. Residents are your checks and balances, they protect you from an unscrupulous or incompetent doctor.

Dr. Heart1: I don’t disagree, but there’s a caveat: If you have heart disease, you don’t want to go to the top heart-disease person at a university hospital. He’s at the top because he’s published the most papers, has the most research money, his name is out there, he gives a lot of talks, other doctors know him, and so forth—but it doesn’t always mean he takes care of patients well.

Dr. Lung: There can be good doctors in small hospitals and bad doctors in big hospitals. That’s why you also want a patient recommendation.

How can a patient get an appointment with a busy specialist?

Dr. Heart1: It’s all about who referred you. If you don’t have someone who referred you to them, then you’re sort of in the general pool with everybody else. The second most important factor is what insurance you have. Doctors will pick. First of all, some doctors don’t participate in some insurances by definition. Second of all, some insurances will pay higher than others. So if you have an insurance that makes the doctor jump through three hoops to order a CAT scan for you and needs preauthorization, yadda yadda yadda, then that’s something that the doctor may make choices on.

Why do patients have to sit so long in the waiting room?

Dr. Baby: For a new patient, I book it for 40 minutes. Some doctors make it ten. For a second visit, some make it five. If you’re an HMO doctor, the network will tell you to see, on average, a patient every seven minutes. HMOs tell us to see more patients; malpractice insurance tells us to take all the time we need.

Dr. Lung: You never know how much time a patient will require. Sometimes they have a bad diagnosis, sometimes they have a family death, and the other day one of my patients was telling me about how her estranged husband was murdered. And she was telling me she was having trouble with her teenage daughter. You can’t rush that situation. I always tell the next patient, “You know, I had a little problem with an earlier patient, so I’m a little late.”

Dr. Virus: When you’re in the room, you’re happy I’m spending extra time with you, because your problem is urgent to you. If I scheduled you for a 30-minute appointment and it goes on for 45 minutes, you will like the interaction a lot. That happens every day, because someone shows up sicker than expected. At the barbershop, they know that every haircut takes X number of minutes, and they can roughly gauge the time. At the restaurant, they know 90 minutes, it’s a rough estimate. But at the doctor, one unexpected problem and you’re an hour behind.

How can a patient get a doctor to really pay attention?

Dr. Heart2: You say, “You know, I’ve heard a lot about you, I’ve heard you’re a great doctor, and I’m really glad that I finally got a chance to come see you.” Something like that. That sets things up extremely nicely. Even if it’s a white lie.

Dr. Baby: The truth is, we’ll spend more time with patients we like. We’ll joke with them, we’ll laugh with them. You have fun with patients you like. People who are obnoxious and pushy, we get the business done and get on with it.

Dr. Heart1: Yeah, you know. I’m on vacation this week. I’m taking “vacation from home,” and I have six patients in the hospitals. I went in to see two of them, and the other four I signed out to another physician. I went to see the two I like.

Is it a good idea to give a doctor a gift if you like the way she’s treated you? Or do doctors feel like they’re being bribed?

Dr. Baby: I think if you had a great experience—if you really have a beautiful baby, say—you can send fruit baskets to the office for the girls. A scarf, a bottle of wine. It doesn’t have to be costly, but personalized is nice. You know, “We talked about your favorite color, and this is something in your favorite color.” Who doesn’t like getting presents?

Dr. Lung: I personally am not into them.

Dr. Virus: They make me feel slimy, but I have received them.

Dr. Heart1: Referring good patients is also appreciated. The stereotypical good patient is successful, professional, able to pay his bills. The less medically complicated, the better. When you think you are doing your doctor a favor by referring everyone you know—and you’re referring them your noodge mother-in-law whom you can’t stand—that’s not cool.

Getting a Doctor’s Attention

“You have fun with patients you like. People who are obnoxious and pushy, we get the business done and get on with it.”

Are doctors unduly influenced by drug companies?

Dr. Virus: I don’t think that doctors make dangerous decisions because of the influence of the drug companies. But I think we make very expensive decisions. There’s an antibiotic for $10 and there’s an antibiotic for $150. I had dinner last night with the $150 guys, and it might be theoretically marginally better. There might be reasons that I prescribe it, and one might be that I liked my steak dinner. You’ll get well either way on the cheap one or the expensive one, but this way I’ll have another steak dinner. It’s low-level bribery—there’s no question about it. I used to go out to dinner with these guys, and I stopped because I found it too gross for words.

Dr. Lung: I used to be in charge of a department, and I told my unit that I’m not going to support big dinners where they take twenty doctors out. If you’re friends with one particular rep, then you can go as friends. But I’ve always felt that they’re expecting something in return.

Dr. Heart2: I am wooed. You know, all doctors are wooed. But the true excess is not in the pens and the steak dinners. It’s the relationships pharmaceutical companies develop with hospitals that are much more nefarious than buying a doctor a steak dinner. Companies strike deals with hospital pharmacies to provide their drugs at a low cost to get patients using them. Then they price the drug at a later date any which way they want.

What are the best and worst times to go to a hospital?

Dr. Baby: Labor and delivery is meant to be a totally functioning unit seven days a week, 24 hours a day. Holidays can actually be great. If you happen to be in an unavoidable labor situation on a holiday weekend, it’s probably not going to be that busy, because everybody that could have been delivered electively has already delivered and all the scheduled sections are done, so you’re going to have maybe even better care.

Dr. Lung: July is the worst. In the hospitals where they have training programs, which most New York hospitals do, July seems to be a very bad month to go because they have new residents coming in. Studies have shown this. Also, another bad time to go is change-of-shift time. In most hospitals, it’s seven or eight in the morning—and eleven to one at night. The old doctor may not tell everything to the new doctor.

Dr. Heart1: I think June would be there right in competition with July. Everybody is sort of tired and looking for next year, they have senioritis, and they’re taking things for granted. You know, in July, you come in, the interns are extra-cautious and things like that. The best time is six months in. That’s when everyone has hit their stride, people have a lot of energy, enthusiasm, so on and so forth.

Dr. Virus: I actually do not believe the July business at all. I think it’s an urban legend. I say never have surgery on a Friday if you can help it because I think the doctors who are on weekend coverage don’t know you as well.

Dr. Heart1: Weekends are complete black holes in the hospital. The worst time to get admitted to the hospital is, you know, Friday noon or later because everybody’s rushing to get out of the hospital, especially during the summer. Their doctors are going to the Hamptons. Plus there’s always that extended weekend elderly drop-off phenomenon.

Elderly drop-off? What’s that?

Dr. Heart1: Families will drop their elderly mothers and fathers because they’re about to go on a five-day vacation and they’re not going to see their parents for a couple of days. And, yes, their parents obviously have lots of medical problems, and they’re things that can be addressed at the hospital, but they could have been addressed two weeks ago at the doctor’s office also. So then, before an extended weekend, sometimes you have a surge, especially in the geriatrics floors.

Has anyone here had to fire a patient?

Dr. Virus: The patients that I’ve gotten rid of have been incredibly verbally abusive to staff or have stolen my prescription pad. We must tolerate anything short of abuse.

Dr. Baby: Well, there are many, but I remember one patient was horribly obnoxious. Every time she came in, there was something wrong. To my staff she was rude and demanding. If she had to wait more than five minutes, it was horrible and it went on for at least a year and I finally sat down with her and I said, “Look, you don’t like me. I don’t like you. Why are you coming to me?” And she started crying and she said, “You don’t like me? I thought you liked me.” And I said, “I didn’t mean that exactly,” and I had to start backing off a little bit, but I said clearly, “I think it is better if you find another doctor. I just don’t think we’re getting along.” She moved on.

Dr. Heart2: It’s hard to fire a patient. There are rules—a patient has to essentially be violent or very noncompliant, but I’ve seen doctors who sort of edge patients out of their practice just because they’re difficult or they display difficult traits that just demand understanding. Or sometimes the patients are just very sick and they take up a lot of time and the doctors are more than happy for them to go somewhere else.

“The worst time to get admitted is Friday noon or later because everybody is rushing to get out of the hospital, especially in the summer.”

What’s the most common mistake doctors make?

Dr. Heart2: One of the issues that I see frequently is overtesting. Someone I know was complaining of arm numbness, so he went to the emergency room and a neurologist there ordered a series of tests: a CAT scan, a carotid ultrasound, an MRI, a transcranial Doppler study, and then a transthoracic echocardiogram. Thousands and thousands of dollars later, there was nothing. He was put on medication, and he was told he was at an impending risk for another stroke. So he went home, and about three days later, the tingling returned and he thought he was having a stroke. So he went back to the emergency room, and the neurologist ordered more tests. It turned out a nurse diagnosed him with a slipped disk, which didn’t require any workup—just Motrin and rest.

Dr. Virus: But patients want the CAT scans. They only think they want Marcus Welby.

Dr. Lung: Would the patient be happy if the person was seen and sent home without a cat scan? They would not be happy.

Dr. Heart2: Patients are coming in and they got on the Internet and they’ve read about some valve problem. So they come in and they say, “Doctor, is it possible I have this valve problem?” How am I going to say, “No, you don’t have this valve problem” without giving all these tests? And if I don’t do the tests, they go down the block to Mr. X cardiologist, who is more than happy to do them. And then they go around telling people, “I went to this cardiologist who didn’t order the tests, and this other guy was so thorough!”

Dr. Baby: My father was a general practitioner, and he would say that you can sit and talk about how an antibiotic is not effective against viruses—but at the end of the twenty minutes the patient will say, “Are you going to write me a prescription for an antibiotic?”

Are most doctors good at what they do?

Dr. Virus: Ten percent are unbelievably horrible, 10 percent are great, and the great unwashed are in the middle.

Dr. Baby: The 80 percent in the middle are adequate.

What is the worst ethical lapse you’ve seen?

Dr. Heart1: I was in medical school, and there was a new surgeon. This doctor was going to perform a new and difficult procedure—a minimally invasive way to do a cancer surgery that usually required cutting the patient wide open.

Dr. Baby: Big operation!

Dr. Virus: Big f-ing operation!

Dr. Heart1: The patient was on Medicaid, of low socioeconomic class, and not educated. I scrubbed in on the case, and a bunch of the hospital’s doctors were there. We did the upper-chest part laparoscopically (using cameras and smaller incisions). Usually, it takes about 45 minutes to an hour; laparoscopically, it took four hours. Not a big deal, it’s a learning curve. But when they start the most complicated part of the operation, the problems begin. There’s bleeding, bleeding, bleeding, but they can’t figure it out. At this point, she’s been under anesthetic for twelve hours, and they decide not to finish laparoscopically but to open her up. The second that decision was made, all the attending physicians left the room and the fellows—the people who are finishing their training—came in.

Dr. Virus: The junior varsity.

Dr. Heart1: It just felt really, really unethical.

Dr. Baby: Well, it’s like the big coronary surgeons. They have their fellows come in—they open the chest, they set it up, they have the vein from the leg, it’s all ready to go … He comes in, he makes one stitch, and then the fellows close him up. So, he did the procedure, but the fellows did all the major stuff that really counts.

Bogus Malpractice Suits

“I just sat in on my friend’s trial, and it was all theatrics. The expert witness brought in an EKG complex, which is usually three to four millimeters long. He magnified it to four feet long and kept on saying, ‘The doctor missed this!’ No doctor would have seen that.”

Dr. Heart2: I think the lesson here is that doctors are self-serving. I know of a patient whose doctor wanted him to enroll in a study. In order to enroll, the patient has to say that he’s short of breath. This patient had heart problems—and the doctor went through every possible maneuver you are taught not to do on a patient with his condition in order to get this patient to say that he was short of breath so that he could enroll him in the study. The doctor proceeded to lie him completely flat, do all the things you’re not supposed to do. This poor son of a gun would not yield. He wouldn’t confess to shortness of breath! The doctor finally gave up.

Dr. Lung: Research is a real problem. Doctors just make up the data. They don’t report negative side effects, no question about it. I used to write the results on my reports that were negative and nobody printed them. Only if it’s positive does it get published in a journal. A doctor I know used to publish papers like nobody’s business, and all the doctors who came and left told me he made up data to satisfy NIH grants and pharmaceutical grants. He was and still is very popular.

Is doctor training better or worse than it used to be?

Dr. Heart1: Worse. The way we used to train physicians is that you worked all the time. You were on call all the time. Medicine was holy work—a calling. It was a privilege and an honor—you should sacrifice everything. Everything else came second. It didn’t matter if you didn’t eat during the day, it didn’t matter if you didn’t sleep. Now, the thinking is, if people don’t sleep they make mistakes, and if they make mistakes it’s bad for the hospital. So residents are being taught medicine as a career choice as opposed to a profession, a calling. They’re being taught as shift workers, which I think is a huge problem. When that clock hits a certain time, they have to leave the hospital. They can’t go to the library and read about the patient. They cannot go to the pathology lab and look up their patient’s pathology on microscope.

Dr. Lung: They look at the clock even as I’m teaching them. They’re looking at their watch three times thinking, This is too long: I can go and find it on the Web. They really cannot find things on the Web, and that is a huge problem.

Dr. Baby: Residents used to have a lot more independence. Now they have to be supervised when they give out a prescription for an anti-yeast cream. Or they have to be double-checked, in every clinic with every patient, by an attending, so that they’ve lost the decision-making, the feeling that this is my patient, I’m a doctor, and I’m taking care of this patient.

Dr. Heart1: That’s important, because these days we have zero tolerance for mistakes. Twenty years ago, that was not the case, and that’s a good thing.

So if you’re a patient in a hospital today, you should be more worried than ever if a resident is looking out for you?

Dr. Heart2: I wouldn’t say they’re good or bad. I’d say if you take an extremely competent physician and you give him too much to do, I guarantee you’ll make him bad. You take a mediocre physician and give him very little work to do and give him three to four patients to take care of over a six-month period, and I guarantee he will excel during those six months.

People complain that hospitals are dehumanizing. True?

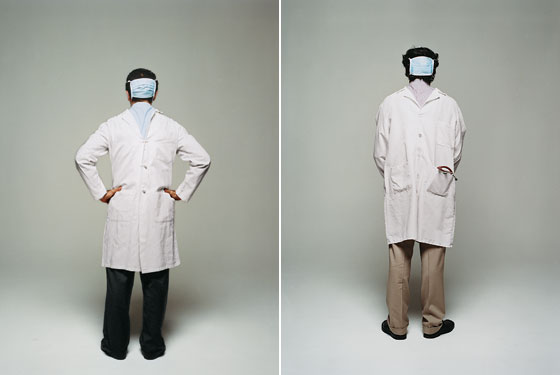

Dr. Lung: Absolutely. Patients get these gowns that hardly cover half the body. And the chairs are not comfortable. At the sickest point in their life, they’re sharing a bathroom with strangers.

Dr. Heart2: The one thing patients are always complaining about is ringing the call bell and waiting 45 minutes for someone to answer. It’s the lack of service, the lack of compassion.

Dr. Virus: Do you think that’s a function of staffing, or is everyone who works in a hospital a schmuck?

Dr. Heart1: In my hospital, we have spectacular nurses who are at the top of their graduating classes. They’re not standing around chatting. If a patient is not being attended to, it’s because there’s one nurse for the whole floor.

Dr. Baby: I know one patient who had a very difficult colonoscopy and they said, “We’re going to keep you in the hospital overnight, just for observation.” So she’s sitting on the toilet and all of a sudden blood is falling out of her rectum and she’s bleeding and bleeding and she’s scared to death to get off the toilet. She’s ringing and ringing and ringing the buzzer and, turns out, it was three in the morning, there’s only one nurse for the whole floor, and she was on the other end dispensing medication. No one was at the nurse’s station to hear the buzzing. When patients stayed in the hospital ten or fifteen days, most of them were still convalescing and a nurse could focus on her three or four acute-care patients. Now they’re all acute. If I were to give patients a very critical piece of advice—if you’re coming to the hospital, bring a family member. You know you gotta bring someone who will sit with you and go get your Demerol for you and help if you fall in the bathroom, because that nurse is giving out meds and she’s got ten patients and she’s got IV lines.

Second Opinions

“I had a patient who needed surgery badly, and she said, ‘I’d like to get a second opinion.’ So she went to a doctor who’s a classic thief. Everybody hates him. A few weeks later, I called her up to find out what was happening. She’d already had the operation.”

Are doctors arrogant?

Dr. Heart2: By virtue of our training and our knowledge, we can get away with things. We can get away with treating patients like shit, and no one is really going to come after us. I’m not talking about malpractice or medical negligence. I talking about arrogance, I’m talking about attitude.

Dr. Lung: They are indifferent. Especially, I hate to say this, men doctors with women patients. Every symptom of fatigue they really say it’s a non-symptom, it doesn’t exist, as opposed to, could there be a cause for this?

Dr. Heart1: You’re expecting doctors to be superhuman beings, you’re expecting them to take fatigue as an important symptom but at the same time not to overtest for fatigue. Are there physicians who are not as sensitive as they should be? Absolutely. As a profession, do we strive for the goal that was set for us by our teachers, do we strive enough? Probably not. Are we close enough to what we should be? No.

Is your ego wounded when a patient says he wants a second opinion?

Dr. Heart1: No, I encourage it. It’s rare that the second opinion is going to differ very much from what you have said. I give them the names of the people I would send my own family members to.

Dr. Baby: It can only make everybody happier—except when the doctor steals the patient. I had a patient who needed surgery badly—it was a scary-looking cyst—and she said, “I’d like to get a second opinion.” I said, “Absolutely.” So she went to a doctor who’s a classic thief. Everybody hates him. I waited a few weeks and I called her up to find out what was happening and she faxed me back her pathology report—she’d already had the operation! She wanted to know what the next step was. I said, “The next step is you’ve got a new doctor. Ask your surgeon—he did the operation.” I’m not here just to do Pap smears and poke around in your breasts. Surgery is what I like to do. You know, office hours are pretty much humdrum. It’s the operating room and the delivery room where you have the—I hate to use the word fun—but that’s where the fun is.

Let’s talk about mistakes you’ve made.

Dr. Virus: I think the confession of mistakes is really this perverse macho thing where we’re really talking about how powerful we are. Every time I hear about people talking about their patient they’ve killed, I think about how they’re talking about how powerful they really are and how they can kill anyone. It’s a hazing thing that we all have to kill a couple to show off how cool we are. Still, there’s no question I’ve made some unbelievably stupid decisions.

For example?

Dr. Virus: When I was an intern, I gave someone fluid and put them into fatal heart failure because I misunderstood what to do. He was someone who was destined to die soon—he had end-stage cancer. But I feel like a crumb about it all the time. But I also feel like I hang on to it because it makes me feel like a powerful guy that I killed someone.

Dr. Heart2: I’ve made mistakes where I’ve missed checking a lab result and the patient ended up dying. I still don’t know that a patient died because I missed the lab result.

Dr. Virus: But you still think about it.

Dr. Heart2: I still think about it, but as you go on in medicine and get more experience, you realize you have much less control than you thought you did. I made this mistake as an intern, and I did beat myself up about it.

Dr. Heart1: When I was a resident, somebody with a severe chronic illness came in with kidney failure and severe electrolyte abnormalities. He was being aggressively replenished with electrolytes, his kidneys were not working yet, and now his electrolytes were too high. So I went through and looked for all the electrolytes that were being given through pills, nasogastric tubes, and IVs, but I didn’t see the electrolytes being added through the bag. So I went home when my call was done, and the next day, I found out the patient coded and died. No one knew what happened. They went back in the code labs and discovered that the electrolytes left in the bag had contributed to the patient’s death. My mistake led to that patient dying.

Dr. Baby: I dropped a baby once. The nurses were calling me into different rooms and the baby fell out of my arms and onto the floor. I scooped it up and somebody said I should have said, “Oh, look—just born and crawling already.” The baby was fine, and I made the decision that when you’re operating, your mind needs to be free of all other extraneous issues.

Long Waits

“At the barbershop, they know that every haircut takes X number of minutes. At the restaurant, they know a meal is 90 minutes. But at the doctor, one unexpected problem and you’re an hour behind.”

What are some mistakes you still make?

Dr. Virus: When I try to be nice to patients and cut ’em a deal. Not a financial deal. But when I’ve made mistakes, it was because I didn’t want to hurt the patient. I’ll not get a biopsy on someone because it hurts, and I should have. Maybe someone has already had two biopsies and I don’t want to get the third, but they’re still undiagnosed and the only way to get there is to get the third biopsy. I hem and haw for a while before recommending it because it’s uncomfortable for them and I’m trying to be nice.

Dr. Heart1: Especially for patients you like, you want things to be okay. Subconsciously, you’ll sort of move toward that realm. So you may not order a test right away because, yes, 90 percent of the time that is benign. I don’t see such a problem with ordering tests. Wanting things to be okay because you like somebody is something to worry about.

What’s the strangest thing you’ve ever seen in a hospital?

Dr. Baby: Once I was sitting in the emergency room and a guy came in and I happened to be schmoozing with one of the nurses at the front desk and he says, “I need help,” and there was this buzzing sound and we couldn’t figure out what it was until he went in and we realized he’d gotten a vibrator stuck up his ass. If you ever put anything someplace where it shouldn’t go, always make sure to have a handle. Put a string on it, for God’s sake, so you can pull it out!

Has the threat of malpractice made you a better or worse doctor?

Dr. Baby: It makes us not better but more conscientious—about sending the follow-up letter, more conscientious about calling the patient three times and saying, “Did you get your mammogram?” In the old days, you could say, “Go get a mammogram, here’s the address,” and then the patient has the responsibility for the next step. We’ve lost suits over, “Oh, yeah, she told me to have a mammogram, but she didn’t tell me how serious it was. She didn’t emphasize it.” I think it’s made us a little bit better about follow-up, about trying to nurture patients in the right direction.

Dr. Lung: Oh, much worse! I just sat in on my friend’s malpractice trial, and it was all theatrics. There was no substance at all. The expert witness—a cardiologist from a very famous hospital—brought in an EKG complex, which is usually three to four millimeters long, and magnified it to four feet long, and kept on saying “The doctor missed this!” No doctor would have seen that—we don’t see it that magnified! The patient died three years after having that cardiogram—and the doctor said he died because this was missed three years earlier. My friend lost the case.

Dr. Heart1: I don’t think about malpractice. The most important thing that a doctor can do to prevent malpractice is to have a good doctor-patient relationship. The doctor who has the good doctor-patient relationship but makes a few mistakes is less likely to get sued than the doctor who does not have a good relationship with the patient and makes a mistake once in a blue moon. The doctor-patient relationship has been shown time and again to be the most important thing.

Dr. Heart2: Overall, malpractice has made good doctors worse rather than bad doctors better because of the fear that you’re missing something and you may be sued for missing a diagnosis. So someone has back pain. You could diagnose a stiff neck with 95 percent certainty, but there’s a 5 percent chance that he could have cancer or a serious infection, and instead of going with your gut, you order a bunch of extensive tests to rule out the improbable.

“I dropped a baby once. The nurses were calling me into different rooms, and the baby just fell out of my arms and onto the floor.”

But does extra testing do any real harm to the patient?

Dr. Heart2: Sure. Procedures have their own risks: unnecessary cardiac catheterization, unnecessary downstream testing when you pick up something that’s not important on a test that you shouldn’t have ordered in the first place. Then you go chasing incidental findings, again, further fear of being sued. So, testing breeds more testing. And it can be a vicious cycle.

What could be changed about the health-care system to better help patients?

Dr. Baby: Universal health care.

Dr. Heart1: But you’re talking from a public-health perspective. If you are an individual … if your dad is sick and he has access to insurance and money, do you want him to live in the country with universal health care or our kind of health care? Our kind of health care.

Dr. Virus: The only place I’d defend American care is for the catastrophically ill, where there are miraculous outcomes still.

Dr. Heart2: If you’re talking about separating Siamese twins, yes, I’d want to do it in the United States rather than anywhere else in the world. When money is not an issue, I would still contend that we have the worst, because we get overtested. We chase incidental diagnoses that might not affect the patient’s health.

Dr. Virus: With universal, you’d get the same kind of mediocre shittiness that you’d get in all other kinds of standardized approaches. But for millions of people, that would be a big upgrade.