Sometime about thirteen years ago, my mother’s brain began to shrink. The signs that something was wrong proliferated slowly, but as ominously as something out of a science-fiction movie.

My mother became unaccountably restless and unable to concentrate. She complained constantly that Larry, my stepfather, didn’t take her out anywhere, that they never did anything—although she could no longer follow the conversation at a dinner party and said things that other people found incomprehensible. She tried going back to work in some of the little tourist shops where she lived, in Rockport, Massachusetts. My mother worked most of her adult life, but now she couldn’t figure out how to run a cash register or follow the simplest directions. Each time, she was fired after a few days, returning home baffled and indignant.

She was becoming indignant a lot. She began to fly into a rage at the smallest frustrations, cursing at herself and at other people in words we never heard her use before. She started to drink as well, something else she had never done much before. My mother had been a classic half–a–glass–of–Champagne–on–New Year’s Eve drinker. Now she had to have wine every night, and even a little made her garrulous and belligerent.

It was as if every part of her personality was being slowly stripped away, layer by layer. The loving, gentle woman my sisters and I had known was being replaced by someone we did not recognize.

There were other things going on as well, physical changes. Her speech was often slurred, even when she was not drinking. Her movements became jerky and exaggerated, as if she could no longer fully control her limbs. She could not abide any restraints. During a drive one Christmas afternoon, I watched while she sat in the passenger’s seat, compulsively buckling and unbuckling her seat belt, again and again, for over an hour. She kept complaining about how it stuck against her body, as if she had never seen or used a seat belt before.

My youngest sister, Pam, and I persuaded her to see a doctor. Her primary-care physician thought she knew what was wrong and sent her to a neurologist to confirm it—but at the last minute my mother refused to keep the appointment. Instead she went on drinking and growing steadily more impatient with everything and everyone around her. She shoved a woman she thought was crowding her at an airport baggage carousel, swore at people over parking spaces.

Mostly she fought with Larry. When he tried to stop her from drinking, she became incensed, threatening to burn down the house they owned together or to blacken over the paintings he sold at a local gallery. Their fights became wild and vituperative. She accused him of being the one with a problem, of being a depressive, of stifling her. A certain mania seemed to come over her during these arguments. Once she did a sort of Indian war dance around him, challenging him to fight.

“I told him, if you want to fight, my family knows how to fight!” she told me. “You ain’t seen nothin’ yet!”

Around that time, I went to Boston to try to intervene. I remember it was a beautiful spring day and we were walking around Beacon Hill. She seemed delighted to see me, but all I could notice was how strange she acted. She hadn’t had a drink, but her gait was wobbly and her eyes looked glazed. She no longer seemed to understand how the stoplights worked. Repeatedly, I had to reach out and pull her back from walking straight into traffic. We strolled down into Boston Common, where a homeless guy on a bench made some innocuous passing comment to her. My mother, always the most private, the most dignified of people, stopped and twirled around, doing a little pirouette for the homeless man, beaming the whole time.

Soon afterward, Larry confronted her with an empty wine bottle she had secreted in their closet. She wrenched it from his hand and hit him across the face with it, cutting his nose. He needed stitches to close the wound, and while he didn’t press charges, my mother had to appear in court under the domestic-abuse laws. I hired a defense lawyer, who got her off with a warning, and finally we prevailed on her to go to a neurologist. This was a full eight years after we first noticed dramatic changes in her behavior. The tests revealed what her primary-care doctor thought all along: My mother was suffering from Huntington’s disease.

Huntington’s (HD) is a hereditary disease, its most illustrious victim the folk- singer Woody Guthrie. It’s caused by a defective gene that produces a mutant “huntingtin” protein. The protein is necessary to human development, but its mutant version produces an excess of glutamines, amino acids that begin to stress, then eventually kill the brain’s neurons. Huntington’s is also known as Huntington’s chorea, or “dance,” for the florid movements that are its most obvious symptom. But such movements do not afflict all sufferers, nor are they the illness’s most destructive characteristic.

Huntington’s is a “profound” disease, one of the few neurological disorders that attacks nearly every area of the brain, says Steven Hersch, an associate professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, and my mother’s neurologist. It affects the cerebral cortex, where thought, perception, and memory are stored. It also shrinks the basal ganglia, which serves as a sort of supercomputer for the rest of the brain, regulating almost everything from movement to the input and output of thoughts, feelings, emotions, behavior. The result is what Hersch terms a loss of “modulation” and “a coarsening” of how we do just about everything—move, think, react. Huntington’s sufferers have trouble correctly reading emotions in others or even recognizing familiar faces. They no longer understand when their behavior is inappropriate, and have difficulty planning, organizing, and prioritizing. They can become both intensely angry and apathetic and indecisive.

“They’re losing possibilities,” says Hersch. “They’re losing the possibilities of things they could do, or think of, or want to do.”

Not the least of Huntington’s effects is what the knowledge of the disease does to its victims. There is no cure. Adult- onset Huntington’s usually afflicts individuals sometime between 35 and 55, although early-onset, or juvenile, Huntington’s can manifest itself before the age of 20. The disease commonly takes ten to thirty years to run its course, as body and mind slowly shut down and leave the sufferer all but inert. Before that happens, victims commonly die from major infections, pneumonia, choking, or “silent pneumonia,” as food goes down the wrong pipe.

Suicides are not uncommon, even among “at-risk” patients who have yet to actually ascertain that they have the disease. Depression is also frequent among such individuals. If one is faced with such a fate, denial can be a survival strategy.

“Often the people who do best are those who can wall it off and go on with their lives,” acknowledges Hersch. “It’s a very good approach in a lot of ways. The trick for people sometimes is to figure out when it’s in their best interest to drop the denial and gain knowledge that will help them.”

The test results devastated my mother. Before long she reverted to denial. She insisted that her test had produced “a false positive.” She told us that she had “the syndrome of the disease, but not the disease itself.” She told us that, somehow, she was “the control” in the test. But as her brain continued to shrink, she began to lose even these words. It became a little joke between us.

“Dearest, I don’t have this, you know,” she would tell me, very seriously, out of the blue. “I’m the—the … ”

“The control?”

“Yes, that’s it!” she would say, delighted.

“Mom, you can’t be the control if you can’t remember the word control,” I would tell her, and she would laugh, and I would laugh. But a few minutes later she would tell me again that she didn’t really have this, you know.

The fact that my mother had Huntington’s meant that I had a fifty-fifty chance of inheriting the gene—and thus the disease—myself. I didn’t like to look at this too directly. That was my own form of denial. I told friends and relatives that I would not take the genetic test that my mother had taken. What was the point, without a cure? It could only screw up my health insurance, and who wanted to live with such a fate hanging over their head?

But those 50-50 odds worked their own havoc. Eventually I found that I couldn’t help thinking about the disease whenever I had trouble coming up with a word or organizing an article. I noticed whenever my body flinched involuntarily. I became especially aware of how often I would drag one of my feet along the sidewalk, or how frequently my left arm would twitch. I took to holding my left hand out in front of me, trying to reassure myself by seeing how long I could keep it still—a better test for delirium tremens, I suppose, than Huntington’s disease.

“Would you stop doing that? You don’t have it!” Ellen, my wife, would tell me.

Yet I was sure that I could feel something deep inside me, something that I came to think of, a little melodramatically, as a stirring. Sometimes, lying awake in bed late at night, I was sure that I was only holding it back by force of will. I was certain that if I let go, I would begin to move compulsively, uncontrollably, just as my mother did now. The dance.

“I think I might have this,” I told Ellen.

“I don’t think you do,” she said.

But her assurance was based on wishful thinking, or the sort of baseless conception one often has about someone else’s life. My wife didn’t want me to have the disease, and she thought of me as a lucky person, somebody who just wouldn’t get such a thing. Yet none of this mattered. In reality, unlike fiction, people’s lives don’t run according to some overarching narrative. We never suspected this disease was in my family before my mother was tested, we didn’t think of ourselves as shadowed by some sort of gloomy, gothic fate. But nonetheless, here it was.

I kept surreptitiously doing my little tests. Should I forget me, may my left hand lose its cunning….

Every step of the way, meanwhile, my mother’s denial only made everything worse for her. It now meant the dissolution of the life she had made with Larry—the quiet days in retirement they loved to spend fishing or reading and watching the news together in the evening; going to their favorite bakery every Sunday morning. None of it was enough to appease what was going on inside her brain. She wouldn’t stop sneaking drinks, wouldn’t keep taking the medications the doctors prescribed to control her moods. We would have been happy to let her drink if that had helped her, but the alcohol only stressed the brain and served to dilute the effects of the drugs. My mother now demanded almost constant attention to keep her entertained, to keep her from wandering into disaster. Eventually Larry told us he wanted out. They had been married for 21 years, and my mother had nursed him through a heart attack, cancer, and occasional bouts of epilepsy. But Larry, an émigré from Middle Europe, had seen both the Nazis and the Communists march into his life, and he knew when to head for cover. I couldn’t blame him. It’s an enormous burden for any one person to take care of a Huntington’s victim, particularly someone who is a senior citizen himself, and he had been dealing with it for a decade. Pam and I hired more lawyers to negotiate the divorce, the sale of their neat little house, the overwhelming thicket of bureaucracy that determined where and how she might live now.

Pam managed to find her a nice studio apartment in an assisted-living facility in Beverly, Massachusetts; a converted high school with the pretentious name of “Landmark at Oceanview.” (Just what was the “landmark”? The last leg of the voyage before you ease into the good harbor of death?) There were big school windows that brought in lots of light, and bright, cheery carpeting, and a diligent staff to make sure that she took her pills and to cook her meals and do her laundry—all tasks that she was having increasing difficulty performing.

My mother’s denial tormented those of us who loved her. But now I found her desire to cling to the life she had known understandable, even admirable.

Personally, I wanted to shoot myself every time I set foot inside the place. My mother, on the other hand, thought it was unbelievably “posh,” the sort of home where she had always dreamed of living.

Meanwhile, my father, whom she had divorced nearly 30 years ago, came east with cinematic notions of getting remarried and taking care of her. He disregarded almost everything we told him about Huntington’s and instructed her that she should just try to concentrate on holding her limbs still. Before one ghastly family dinner in a restaurant, he let her have a drink, then tried to cut her off. When his back was turned for a moment, she calmly snatched up his full wineglass and downed the contents in one swallow. I saw his eyes widen. My mother spent the rest of the meal barely able to speak, rolling her head back to try to get food down, until we made her stop out of fear she would choke to death in front of our eyes. My father fled back to his apartment in Hollywood. Good-bye, Golden Pond.

I was determined by this time to face the disease head-on. If my mother had made everything worse for herself by remaining in denial, I would throw it off. I would take whatever medications were necessary, volunteer for whatever experimental programs there must surely be. I convinced myself that this was a purely practical idea. Why go about looking for cures or ways to ameliorate the effects of the disease if I didn’t have the gene? Looking back now, I think my decision may have been more emotional than anything else, a desire to know this and be done with the uncertainty. I told myself I would be stronger than my mom, and take whatever I was given. Early in 2007, I set up an appointment at Columbia University’s HDSA Center for Excellence, located up in Washington Heights.

The Columbia Center deals with every aspect of the disease, both for those already suffering from HD and for those at risk, and it endeavors to help patients through each stage. It’s unique in that the care it offers is free, although there are nominal fees for some parts of the gene test. The center’s testing protocol, established and refined over the fifteen years since the Huntington’s gene was first identified, is actually an involved process, one that takes place over a few months—and is an infinitely better one than what my mother went through. One of its chief purposes was to slow me down—to let me think over what I was doing. As the center’s genetic counselor warned me at the start, “Once you know, you can’t not know.”

There was the session with the genetic counselor, a visit to a psychiatrist, neurological and neuropsychological exams. If after all that I still wanted to know, they would draw my blood and tell me the result of the gene test. That result would be a number—the number of times a particular string of glutamine DNA, known as CAG, repeated itself at the beginning of my Huntington’s gene. If that number was 27 or below, I was in the clear. If it was 36–39, I would fall into a tiny percentage of the population that might, or might not, develop the disease. If it was 40 or more, it meant that I had inherited the defective gene—and that I would get the disease.

I threw myself eagerly into the testing process, glad now to be doing this, to be confronting these phantom fears. The not knowing by now had become as bad as knowing the worst could possibly be, I told myself. I disavowed everything I had told people before. Best to look this fate in the eye, to see if it really was waiting for me.

The initial exams went well. The doctor found no signs that I had the disease already (my twitching left arm promptly stopped twitching so much). But the doctor seemed less than pleased that I was taking the test at all. The genetic counselor had insisted that there was no right or wrong reason for wanting to take the gene test, but it seemed clear that I had made the wrong choice.

Later, I found that I had misinterpreted the doctor’s attitude. There really was no right or wrong reason to get the test, she was simply a little surprised by my motives. Most of the people they saw came because of some life trigger. They were making career decisions, getting married, thinking of having children—or wanting to spare their children, now marriage age, from having to take the test. Or they had just learned that Huntington’s was in the family, or that a genetic test existed.

Getting tested so that you could see what you could do about the disease was unusual … in part because there is currently nothing you can do to cure the disease or even curb its progress.

Huntington’s is what the federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA) officially calls an “orphan disease”—it affects too few people to make it worth the drug companies’ while to develop a drug for it on their own. The official cutoff number is 200,000 people; Huntington’s currently afflicts only 30,000 to 35,000 people in the United States, with perhaps another 200,000 to 250,000 at risk of getting the disease.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) provide subsidies in such cases, but the total amount spent in the U.S. on finding a cure this year will probably be no more than $120 million to $130 million. A substantial sum, to be sure—but not so much when you consider that it can easily cost drug companies $1 billion to come up with an effective drug. As it stands now, a cure is not on the horizon. The most promising idea seems to be “turning off” the defective Huntington’s gene, but discovering how to do that presents a host of technical problems that remain far from solved.

The doctor’s surprise at my motives drew me up a little short—not a bad thing. Getting tested for the gene of a hereditary disease with no cure is and should be a hugely complicated decision, one with implications beyond one’s own self. It can mean “outing” other family members, who may have no desire to learn if they will get the disease. It can mean any number of problems with one’s health insurance (no doubt a big reason why fewer than 3 percent of at-risk Americans get tested for HD, as opposed to 20 percent of Canadians who might have the gene). It can mean dealing with unanticipated feelings of guilt, dread, despair. It all made me think again. Was I engaging in a reckless act of bravado, moving into a realm that I was not psychologically or emotionally prepared for, just to show that I could do it?

“No matter what the result is,” my genetic counselor warned me, “nobody is the same person they were when they walked in here.”

I was pretty sure that if the results were negative I would be the same person I was in about five minutes. On the other hand, the 50-50 chance that I had the gene had already begun to unravel any peace of mind about my future. Bravado or not, I had to know. I had them draw the blood. They told me it would take two to four weeks for a result, depending on how crowded the lab was. No matter what the verdict was, I would have to come back to the clinic for the counselor to tell me in person.

During my trips to the Columbia Center, Ellen and I would sit in the plain, institutional waiting room and watch other outpatients coming and going. Some displayed no outward signs of having the disease; others clearly had the telltale movements. Some of these people carried themselves with remarkable bravery, others were so young that it was almost unbearable to watch them. I knew that, in a very short time, I would either walk away and never see them, never see this place again, or that I would join their small fraternity.

The two to four weeks that I had to wait seemed to stretch out like a lifetime—in the best sense of the words. I put the possibility of having the gene out of my head again, and was more sanguine about my chances than I had been in months, still buoyed by the revelation that all my twitching had been, so to speak, in my head.

Only one afternoon, while I was working in a library, did the full understanding of what I was doing sneak up on me. What if it really is positive? I thought to myself, out of the blue, and I realized that I had no answer. I was stepping over a cliff, into a state of mind that I had no real way of even imagining. I quickly went back to my research, shutting this idea safely away again behind my own walls. But it was still there.

“Once you know,” the clinic’s counselor told me before I was tested for the mutant gene, “you can’t not know.”

When the call came two weeks later to set up my appointment, I wished for more time. I had two days to wait. I joked with my wife that our appointment was on an auspicious day—the anniversary of Hitler’s invading Russia. But I also couldn’t help wondering, “If it’s negative, wouldn’t they tell you over the phone? I mean, even if they say they won’t? Just to give you peace of mind, as soon as they can?”

“No, they have a whole procedure,” my wife insisted. “It’s going to be fine, you don’t have this.”

“But I’m just saying. Wouldn’t you tell the person? Wouldn’t it be sadistic to let you wonder for the next two days if the news was good?”

“It’s a procedure!”

We took the subway up to the center and got there a little early, seating ourselves in the waiting room again. Almost as soon as we arrived, my genetic counselor came out to see us—and we had our answer. When she walked into the waiting room we could both see that tears were welling up in her eyes, and that her mouth was set in a tight little smile, like someone trying to pretend there’s nothing wrong. It was like being on trial and having a jury come back that won’t look you in the face. After that, it was all over very quickly. The counselor sat us down in her windowless office and told us at once that the number of my CAG repetitions was 41—one number higher than my mother’s. I had the defective gene, and my brain, too, would begin to die.

I can’t say that I was immediately stricken or horrified. I didn’t even feel as upset as I have sometimes when an editor hasn’t liked a manuscript. It felt, as bad news often does, as if I’d known what it was going to be all along. Outside, it was still a sunny early-summer day. We got back on the subway. Ellen tried to be consoling, but I wasn’t in need of any, not just then. What was there to say? When we got home, I got a call from a podiatrist wanting to move up an appointment for a minor foot problem I was having. I hustled over to the East Side and there I sat, in another doctor’s waiting room, not an hour later. It all seemed unreal, like some weird simulation of what I had just been through. I thought about how giddy I would have been feeling if the results had been negative. I felt like blurting out the news to anyone I encountered, I just found out I will get a fatal disease. But I didn’t. The doctor prescribed some egg cups for my shoes, and I went home.

A couple days later, the bottom fell out. I was working at my desk when I began to doubt every single thing that I was writing. I was certain that I was already losing my ability to think, to put together a simple sentence. Later that night, lying in bed, I was gripped by a terrible, souring sense of dread, a feeling that everything in my life was useless, meaningless. I had never experienced anything like it before. I am a person of faith and optimism, at least when it comes to my personal outlook, but all that gave way before this wrenching, physical sensation of despair. This feeling came over me several more times during the week after my test. Nothing, not even the most soothing and optimistic thoughts I mustered, could ameliorate it. I wondered if this was what true, clinical depression felt like.

Then it would fade away and I would feel strangely exhilarated, just as one does when a fever passes. I learned to ride these moods out, just try to get through them, and soon they largely disappeared. I was, I suppose, building a new wall. All that brave confrontation, just to escape behind a new layer of denial! Nonetheless, everything did seem more intense, more edged. My moods were more mercurial, I was angrier, more sympathetic, even more apathetic about things—always aware that these very mood swings, too, were symptoms of Huntington’s.

I made predictable resolutions. I would live more in the moment. I would hone my life to the essentials; read more great books; stop wasting so much time on newspapers, the latest catastrophe from Africa or China, or the op-ed pages. Who had time for it? Instead, I would write and write and write, build a legacy of work.

Yet this soon created its own sense of panic. I had easily twenty, thirty, maybe more good ideas for novels, histories, screenplays—how would I ever get all that done? What I really wanted was to live like I always did, taking little care of myself, wasting time worrying over politics, or how the Yanks were doing, or even the banality of other people’s opinions. As a novelist I learned long ago to pace myself, building something day by day, rewarding myself along the way with all the sweet distractions of modern, urban life. I wanted my trivialities. I kept thinking of the title of that self-help book, something like Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff—and It’s All Small Stuff. But of course it’s the small stuff that we crave. That’s what gives us the illusion that life is infinite, the only thing that saves us from the terror of consciousness, the root of which is that uniquely human knowledge that we are going to die. My mother’s denial did indeed make everything worse for her, and at times it tormented those of us who loved her. But now I found her stubbornness, her desire to cling to the life she had known, understandable, even admirable.

I started to tell people about my test results, what they meant. This made my wife uncomfortable, but I couldn’t help myself. I had some kind of compulsion to tell friends, family, even professional acquaintances. I wasn’t sure why I felt this need. Was I trying to solicit their pity, their admiration? See how brave he’s being!

Probably. But I think I was also doing it out of sheer incredulity, or even as a cry for help. Here I am dying. Do something!

My friends duly praised my courage—as if I had any choice. They spoke about all the great things going on in medicine today. I nodded and smiled, told them yes, I would pursue every cure. But there are no cures, at least not yet, and I doubt that a nation bent on spending three or four trillion dollars on the grand task of making the Iraqi people learn to love one another is ever going to devote much more to solving my little brain ailment. For that matter, I can’t honestly say that my disease should have any priority over the likes of breast cancer, strokes, heart disease, or any number of other maladies that affect many more people.

All things considered, I knew that I had already had a phenomenally good life. Even when it came to the Huntington’s, I had been lucky enough not to live with the disease hanging over my head. I was never somebody who worried about death or thought about it much at all. My wife and I had fortunately decided not to have children, a decision we reached more or less by inertia over the years and which meant that, thank God, I didn’t have to worry about having passed this on to someone else.

And yet, inevitably, I would find myself filled with rage at times. I thought maybe it was the knowing that made all the difference. I joked about the old Woody Allen lines, from Love and Death: “How I got into this predicament I’ll never know … To be executed for a crime I never committed. Of course, isn’t all mankind in the same boat? Isn’t all mankind ultimately executed for a crime it never committed? The difference is that all men go eventually. But I go at six o’clock tomorrow morning.”

But I wasn’t going tomorrow morning. No one is sure what triggers the onset of Huntington’s. The gene’s interaction with other genes, or environmental factors, or even aging itself may play a role. Heredity and especially gender seem to be very strong factors. The disease could begin to take its toll at almost any time, but because I inherited it from my mother instead of my father, it is more likely to manifest itself around the same age when she got it, at 65 or maybe even older—a very late onset.

“The brain copes, until it can’t anymore” is the exquisite phrase with which Herminia Diana Rosas, an assistant professor of neurology at Mass General and Harvard Medical School, describes the progress of the disease. Huntington’s may well be active in the brain ten, even twenty years before any symptoms begin to show up. We don’t see its effects because the brain rallies to adjust. In a touchingly human response to this threat, the neurons compensate by trying to do less, or by sharing vital information among each other, squirreling away knowledge and memory where they can.

In other words, I had not received some fatal diagnosis, not really. All my Huntington’s gene guaranteed was that I was going to start to die, most likely at the same age that many people start to die, from one thing or another, prostate or heart disease, stroke or diabetes or Alzheimer’s—much as we are all dying, all the time. I might have another good sixteen years ahead of me, maybe even more. I joked that it was like being on death row, only with better company. I joked that it was like being on death row, only with better food. Coming out of my agent’s building on yet another gorgeous summer day—and what a beautiful summer it was—I told myself, “You’ll be doing this ten years from now, and you’ll still have six years to go. Think of how long that is, how much will happen and how much you can do!”

What I really feared was not death but what would precede it. Dr. Hersch’s “coarseness” meant a lack of nuance—a great prescription for a writer. I would be unable to work, to organize my thoughts or comprehend the world around me. I would forget friends, names, faces, facts, memories. I would be unable to control my moods, my movements, my urges, would become a living caricature of my former self—much like what I had seen happen to my mother.

Our efforts to get her to adjust to life at her assisted-living facility were breaking down. She became belligerent if she felt she was being mistreated or thwarted in any way. She kept insisting that she wanted to be married again, kept pursuing men of any age. When someone told her that a 95-year-old fellow resident at Landmark had said she was nice, she harassed him to the point where she had to be forcibly removed from his room, slugging a female staff member in the process.

This time she was ejected from the facility. After a brief and volatile stay in a nearby nursing home, my mother was shipped out to a psychiatric ward, where she was drugged nearly to the point of being insensible. She couldn’t speak, could barely move, and seemed to be experiencing hallucinations. My sister, noticing other inmates walking around dressed in some of her clothes, raised hell, cajoled doctors, and managed to get her transferred to a much better facility, a sprawling state hospital. It was a place with light and space and a dedicated staff that adjusted her medication so that she was alert and talking again. She seemed much happier, the violent rages ebbing away, but all the transfers, and the progress of her disease, had taken its toll. She had trouble completing even a simple sentence, and her gait was so unsteady that she was confined permanently to a wheelchair.

There was no disguising that she was in an institution now. Her ward was all tile and linoleum, and she was surrounded by other inmates suffering from advanced neurological disorders, Huntington’s and Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis, retardation, and dementia. There was one man, younger looking than my mother, who just sat about with his head crooked permanently to one side, his tongue lolling out of his mouth. Another woman, all but immobile, told us how she had been a nurse for many years but was now suffering from Parkinson’s. She seemed to be alert enough and in her right mind.

Which was better? To be past any awareness of your condition—or to be sinking slowly into it, still conscious? I wondered what the point was of trying to extend the longevity of the human body before we knew more about preserving the mind. How much would I understand when I was put in some institution like this? Ellen swore that she would take care of me at home, and I knew she meant it. But I also knew that in the end, she would not be able to do so, that this was my fate I saw here before me.

Visiting my mother was an ordeal to me now. And yet it also felt oddly soothing to just sit with her in silence, while she patted my arm and smiled at me, saying little. It occurred to me that she was tracing the path I would follow. It reminded me of The Vanishing, that creepy European film in which a man is so guilt-stricken over not knowing what became of his lover that he allows her psychotic killer to kill him in the same extended, horrifying manner, just so he can know what she experienced. When my mother first went to live at Landmark, my sister persuaded her to give up her car; her deteriorating physical skills made her a menace to herself and to others on the road. But Pam gave her a few weeks first to get used to the idea, to ease her transition to living on her own, in a strange town, at the age of 75. My mother would usually drive back to Rockport, a place she loved, a place where she had lived for nearly 40 years, and where she no longer belonged. There she would just sit in her car, out on the town wharf, and watch the gulls circling and diving over the harbor. I often thought of her there, and now I understood that I would, one day, know what she was going through.

A Huntington’s drug trial materialized late last year at a Mass General clinic up in Charlestown, Massachusetts—the first interventionary test ever, for at-risk subjects who as yet had displayed no symptoms of the disease. I volunteered immediately. The trial consisted mostly of taking daily supplements of creatine, the bodybuilding drug, which, it was thought, might strengthen and extend the life of neurons. It wouldn’t “cure” the disease, but at my age, preserving as many brain cells as possible—buying time—might prove almost as beneficial.

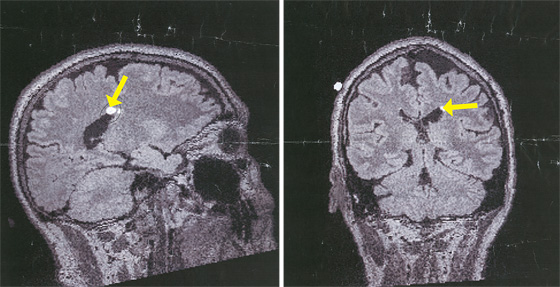

The first step was another battery of tests, starting with an MRI. When it was over, I got to see a picture of my brain for the first time. Dr. Rosas, who runs the program with Dr. Hersch, her husband, told me that there were no visible signs of Huntington’s yet and pointed out the caudate nuclei, the parts of my brain that were most likely to shrink first. They lay along the edges of the pool of cerebral-spinal fluid that separates the left and right hemispheres of the brain—an area that looks like a pair of dark wings on the MRI, delicate and beautiful. I stared at them for a long time, thinking of how someday the wings would lose their shape as my brain shrunk and they expanded, leaving only more of the blackness.

There was something else on the scan as well. A little white circle, maybe half the size of a dime. Dr. Rosas wanted to know if I’d had any headaches or violent seizures recently. I had not, but it seemed the suspicious little dot could be a tumor in the making. More tests would be required, through my primary-care physician back down in New York. Oh, and it also seemed that I had a cataract in each eye.

I left the clinic in Charlestown before they could diagnose me with malaria or dengue hemorrhagic fever. It took most of a month to get a more detailed cat scan and learn the results. I didn’t really think I had a brain tumor, since I didn’t have any symptoms. I told myself, half-joking, I cannot get two brain diseases in the same year. But I knew enough now not to try to outguess the tests, and the waiting began to drag on me. A few days into the New Year, I went to get those cataracts looked at. They proved to be no real problem, so small now there was nothing to be done but wait for them to grow. Still, coming back from my ophthalmologist’s, I could barely see through my dilated pupils; struggling to dial the number on my cell phone for the MRI results that were due back that same day. Staggering blindly up Riverside Drive, on a blustery January day, the wind whipping at my face and hair, I had to laugh, thinking how my life was turning into a road production of King Lear.

This time, the news was good. I didn’t have a brain tumor. The little white dot was nothing at all. One brain disease to a customer. There was life, there was hope. There was the recognition that all I was going through—the torment of an aging parent, the knowledge that I would likely follow in her footsteps—was really nothing that unusual in our America of aging seniors and genetic testing. What was to be done but to make the most of it?

Back at home, I looked at the scan with my wife. “I’m going to miss that brain,” she said.

“I know,” I told her. “I’m going to miss me, too.”