Steve Crohn seemed almost euphoric, as if relieved to be checking off items on a list that had grown overwhelmingly long. In July, he flew to London to install one of his paintings in the home of the friends who’d commissioned it. Back in New York, he caught up with emails, left messages on machines, never mentioning or exhibiting any despair. Over lunch with the dean of his alma mater, he offered to provide photos he’d taken in the ’60s for an exhibition on the civil-rights movement. To his younger sister he mailed a birthday card featuring a tabby cat, apparently knowing full well the circumstances under which it would later arrive. He made lists of his bank accounts and passwords. Check, check, check.

And he finished his maps. For his entire life as an artist—he was now 66—he’d had to support himself and give structure to his existence with various day jobs: copyediting, magazine production, interior design, social work. But proofreading for Fodor’s was his longest-running gig, and perhaps the most congenial. He could do it from home, or what now passed as home. And for a punctilious person, it could be oddly satisfying. He would carefully read the manuscripts of travel books the publisher was preparing, compare the texts to the maps, and make sure everything mentioned in one was accurately pictured in the other. This time, this last time, he saw that the restaurant 2 Fools and a Bull was missing from the Oranjestad detail. The Tropicana Aruba resort on Eagle Beach had also gone missing. He neatly noted these mistakes, then brought the completed work to the Random House building, leaving it at the lobby desk. This was last August, Thursday the 15th, 1:30 in the afternoon.

Perhaps you saw him that pleasant day: one of those friendly-looking gay New Yorkers, aging but not old, thick but not fat, six-footish, with blue eyes and a slight dusting of ginger in the white fuzz haloing his face. Beefy worker’s hands, yet with a fine gold band on the right ring finger. Busy like someone with lots of work and places to be—though this was a front. He was freelance in the largest sense: unattached, perhaps unattachable. Most of all he was a survivor, which to him meant not just being but being special. He smoked Dunhills. Brushed his teeth with Vademecum. Was hearty with strangers, dapper at cocktails, cultivating the air of a wealthy eccentric despite his Social Security check. He dressed just so: often a neckerchief jauntily affixed, a beanie or a bolo tie, a popped collar, interesting socks. He had the verbal flair of Oscar Wilde if Wilde had 12-stepped. “Darling!” he’d call anyone. Or, an encouragement: “Go you!”

The obituaries got a lot wrong, but this much was right: Stephen Lyon Crohn didn’t die of AIDS. Not dying of AIDS was in fact the reason he got obituaries at all. Certainly it wasn’t because of his hundreds of artworks, however beautiful; few people had seen them. Being the great-nephew of the great Burrill Crohn—the doctor who described and gave his name to the chronic inflammatory disorder—was a piquant detail but not the point. No, it was Steve’s own medical description that earned him inches in the Daily News: “ ‘The Man Who Can’t Catch AIDS’ commits suicide at age of 66.” Or, as the Los Angeles Times put it: “Immune to HIV but not its tragedy.”

It was true: Steve was one of a surpassingly small number of people on Earth whose bodies essentially ignored HIV. And he was one of an even smaller subset who had occasion to find out. Back in the early 1980s, at a time when thousands of gay men, including dozens Steve knew and loved, began dying, he kept on living. Surely he’d been multiply exposed, and yet as he waited a year, and then many, to join those he’d lost, he came to realize that his body would not give him the chance. Frantic to find out why, he went from doctor to doctor, all but begging someone to study him; when eventually someone did, a great discovery was made. Not only had he inherited a genetic mutation that spared him, but that knowledge would lead to the development of a drug that even now helps sustain the lives of people not as lucky as he. “He realized that he could provide a piece of the jigsaw,” one researcher said, “and he was right.”

Steve, whose story was told in medical journals and in a 1999 Nova documentary, ought to be known as one of the heroes of the effort to dredge knowledge and life from death and disaster; perhaps he sometimes saw himself that way. And yet, having delivered his maps, having removed his ring, paid some bills, made some donations, and dealt with a hundred other details, he killed himself on Saturday, August 24. That he did so some 30 years after AIDS first spared him gave the headline writers their hook. Every obituary mentioned survivor guilt, as if this term, borrowed from the Holocaust, were a clear explanation. In fact, it was a provocation. One online commenter wrote: “If he cared about others he would have stayed healthy to help find a cure for others.” Another: “A horrible, pathetic, loser. He WANTED to get AIDS … Selfish … He had NO problem, so he killed himself.”

Even his two sisters were bewildered by the contradictions packed into the suicide. When Amy—same father, different mother—went through life-threatening medical crises in 1997 and 1998, Steve cheer-led her recovery. (“I’m not having any of that,” he’d say if she quailed.) Yet now the man who helped her live had chosen to die? What did being a survivor even mean, if it brought you to a greater despair? His sister Carla—same mother and father—began to wonder how long he’d been planning. (When she called his former therapist with news of the suicide, the receptionist said, “I’m not surprised.”) The card Amy received shortly after his death only deepened the mystery. Aside from the tabby on the front (she’d once had a tabby), it featured, inside, this handwritten wish: “Happy birthday and enjoy gift.” But there was no gift.

Once, he thought the world of himself. He knew his genius. (He joined Mensa so everyone else would know it, too.) But if in his youth he was a Jewish prince, he saw himself as a displaced one, caught on the wrong branch of a complicated family tree. His father, Richard, was the wise-ass black-sheep son of the black-sheep brother of the Ur–Crohn genius Burrill, whose other descendants were wealthy pillars of Manhattan Jewish society, not backwater suburbanites. Still, the Crohns of Dumont, New Jersey, tried to keep up appearances. They talked about things intellectual, sometimes in French. They made sophisticated choices. When Richard and his vivacious wife, Janet, divorced, Richard, in his mid-30s, took Steve, not yet a teen, to live with him in a bachelor apartment in the city. That didn’t work; a few months later the snobby little aesthete came home to Mom in Dumont. He desperately wanted to love his father, but his mother knew how to love him.

Though both parents were liberals, Steve’s teen years were a struggle between a desire for popularity and the unpopular implications of his emerging sexuality. It was his habit on Saturday mornings in high school to go into Manhattan with a friend, start shopping at B. Altman’s, and work his way up to Saks, hitting every department store and bookshop on the way. He’d buy sweaters no other kid in Dumont could appreciate. His room was plastered with Impressionist, then Expressionist, postcards. But as his palette expanded, his tastes grew more specific; not many suburban teens in the early sixties read, as he did, the Mattachine Review, that early harbinger of gay revolution. No one told him not to. If they had, he wouldn’t have listened.

The downside of high standards is frequent disappointment. You tend to move on, if you can. Before his first year at the University of Wisconsin was over, he’d joined Martin Luther King’s march from Selma to Montgomery; that was the end of Wisconsin. He identified (as he wrote then) with King’s struggle to “blunt the horns of prejudice”: He’d been gored by those horns himself. Sleeping with men but still dating women, he wrangled with his gayness for years, even after moving to a fifth-floor, 64-step walk-up in Hell’s Kitchen in 1965. It was the first of his paradises, his Utopias, his Brigadoons.

New York seemed to be waking up from a cold sleep then, as, at 19, did he. He let his bright-red Jewfro fly. He danced at the Dom. Friends not interested in pot and LSD were replaced by new ones who were. He studied at Cooper Union and the Art Students League, dabbled in Buddhism, protested the war, and did not scruple, as the ’70s wore on, to expose teen sister Amy to his louche doings. She got high just walking into his apartment, with the walls he’d painted acid green. When she asked about gay men’s promiscuity, he said that was just how it was in their culture.

His liberation poured into his art, the still lifes and landscapes of his youth now blurring into something more abstract. (He finally got his bachelor’s, in fine arts, at City College in 1972.) He even began, by the end of his 20s, to acquire a small reputation. If he had to copyedit at Business Week to sustain himself, Business Week returned the favor, in 1976 listing his art as a good investment. Not that he sold much; he priced everything way too high.

“One day he began to feel ill,” Steve wrote in a story called “Stephen’s Journey.” “And in the next weeks he developed all kinds of little infections, particularly in his throat.” The uncanny metaphor, years before AIDS, was part of an illustrated fantasy about a young artist’s heroic search for vocation. In it, a white horse pulling a cartload of coal arrives to take him on a great journey. The coal “began to glow with a strange familiarity.” Each piece represents something he must leave behind: family, friends, even self-doubt. He tosses them to the street until only one remains: the most beautiful painting he has ever seen. (It bears his own signature.) “Must I give this up too?” He must: “The journey is more important.” His infections and pain disappear. But so does the horse.

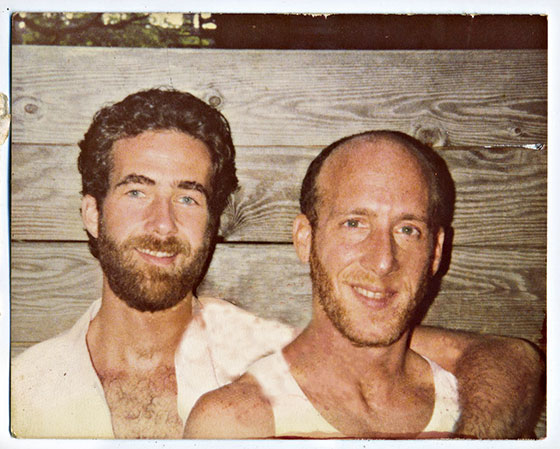

On a cold night in January 1979, Steve, then 32, met Jerry Green at a “casual yet sexual loft party” in the Flatiron District. Jerry’s “physique was lean, muscular, and supple from the gymnastics he practiced,” he wrote later in an unfinished memoir, whose chapters are mostly named for Beatles songs. “I always thought he had the romantic looks of an Arabian prince—a Jewish version of course—but there was something exotic about”—and here chapter two (“Got to Get You Into My Life”) breaks off.

Though he had a master’s in biostatistics, Jerry was working as the executive chef at the Whitney Museum. He was 32—and brushed his teeth with Vademecum! But shy and tight, he was quite a contrast to light-up-the-room, bombastic Steve, who never failed to produce an opinion, a trait his gay liberation only enhanced. He and Jerry “held hands discreetly” while listening to Montserrat Caballé at Carnegie Hall, but discretion anywhere else was prudish: “We rejoiced in our bodies’ freedom.” As, it seemed, did everyone. Jerry’s friends Ben and Marty were open about their open relationship; Jerry himself trailed a long-distance lover. Still, he and Steve felt the click of unique human connection between them. They fit. For Steve, the proof arrived with a bout of hepatitis just a few weeks after they met: Jerry devotedly nursed him through. Here was a man he wanted to love, who also knew how to love him. “I would live for your pleasure alone” was the phrase Jerry had pointed out in the program at the Caballé concert. Steve was, for once, less poetic. “They say when you find someone who tastes good …” he wrote. “Well, Jerry Green was delicious.”

His father, courting a new wife, could hardly object when Steve broke the news of his own new love. In fact, he was delighted, if less than completely informed. He “danced around the apartment like a leprechaun” and said, “I hope I get to meet him/her someday.”

But it seems he never did. Steve and Jerry moved to Los Angeles before the year was out, and news from the Coast was sporadic. For one thing, Jerry soon opened a restaurant called Eats, on Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood. Steve designed the logo and the ads, in which menu items zoom across a brilliant night sky.

And they worked on their house on North Alta Vista: an art-filled 1927 Spanish-style bungalow with a red-tile roof, a small front yard, and dining chairs upholstered in fabric Steve painted. Friends who visited in 1980 found him happier than he’d ever been; at last, he said, he had a “soul mate.” But everyone in gay L.A. seemed happy then: “We had the music, we had disco, we had drugs,” Steve said later, “and we could dance all night and fuck all day.” Photos of the gang at Eats, with their de rigueur mustaches and tight-fitting tees, are so full of gay promise they might as well be time-stamped t-minus :01.

It seemed to be a flu, at first: nothing to worry about. In January 1981, AIDS wasn’t even a name, let alone an epidemic. (The U.S. death toll was in the single digits.) Doctors called what Jerry had an FUO: a fever of unknown origin. Its destination, however, became clear after another year. By then Jerry was blind in one eye and spotted with lesions from Kaposi’s sarcoma; Steve watched in horror as “a handsome man’s body … aged 60 years before my eyes.” It was, he said, “like The Exorcist.” Though he tried to care for Jerry as Jerry had cared for him, Steve was panicked and furious. Being from a medical family, he thought intelligence and connections should solve the problem; being spiritual, he thought Jerry could heal himself with visualizations and positive thinking. Neither worked.

On March 4, 1982, Gerald Edwin Green, 35, the son of Max and Ann Green of West Newton, Massachusetts, the operator of a food store (as the death certificate put it), died of cytomegalovirus pneumonia at Brotman Medical Center in Culver City. His marital status, provided to the clerk by his father, was “never married.”

Steve rarely produced a still life or portrait again. In the 1980s, a new style emerged: He’d baste a large canvas with color, mask it with tape, paint more, tape more, rip the tape, paint and tape and rip. Almost no imagery survived the process. A work called Parrot Garden from 1981 is mostly black: no parrots, no garden.

By then Jerry was gone; in some ways it seemed he had barely ever been there. Only three years and two months had elapsed between the “casual yet sexual” loft party and the emaciated corpse. And if it was possible for someone to vanish even further, Jerry did. The Greens, who treated Steve with “bitterness and hate and shame,” cut off all contact, refusing even to tell him where Jerry was buried. And how long would it be before Steve joined him? As FUO became “gay cancer” became grid became AIDS, and AIDS was discovered to be sexually transmissible, Steve understood it was just a matter of time.

And so, with nothing left for him in California, and needing, as he said, “to be held,” he abandoned his second Utopia in 1983. A friend named Ron Edwards helped him pack for the cross-country drive; along the way, in Santa Fe, he visited another, Kris Johnson, a painter.

Johnson died at 33 in 1985. Edwards died later that year, at 47. Jerry’s friends Ben and Marty died in 1986 and 1989, respectively. By the end of the decade, most of the gang in the Eats photos were probably dead too. (Danny Adams, the photographer, died in 1989.) Overall, something like 70 members of Steve’s circle died of AIDS. Yet he kept not dying. That he was one of the lone survivors of the early war did not leave him less shell-shocked. He even wondered if, by living, he was somehow letting his friends down. This was the survivor guilt, and its incessant restoking with fresh deaths and memorials nearly deranged him. His family often found him in a shut-down state, talking strangely or just being “off.” He noticed it too. “The open wounds of loss need time,” he wrote. “If there is time.”

Over the next ten years, back in Hell’s Kitchen, he had dates and flings—practicing “safer” sex—but found no new Jerry. At Amy’s wedding in 1984 he was supposed to catch the bouquet; she overshot and hit a window. Though increasingly hypochondriacal—every minor ailment was a sign that HIV had finally breached his defenses—he kept walking toward his fears. There were grief groups, support groups, caregiving, counseling. (He received a Master of Social Work degree from NYU in 1992.) When he volunteered with AIDS patients, at a time when many people were afraid to go near them, he’d say: “Honey, if I’m going to get it, I’ve already got it.” And since he was, for the moment, alive, he had to live. Visiting an old friend in San Francisco in October 1989, he experienced the Loma Prieta earthquake; afterward, he leaned his head out the window and shouted to the wide-eyed neighbors and fluffed-up cats, “That was fabulous!”

Though fewer, the deaths kept trickling in; eventually there was almost nobody left. And some deaths were floods in themselves, including his mother’s, of breast cancer, at 67. Later, he’d tell Amy that he couldn’t imagine wanting to live past that age. From then on he wore her gold wedding band on his right ring finger.

By the time Dr. William Paxton drew his blood in 1994, Steve had spent years telling anyone who would listen that he must have some kind of natural resistance. At family parties he buttonholed Crohns affiliated with medical research, who said, yes, yes, he should be examined. Still, phone calls failed to turn up any studies of HIV-negative men. Why weren’t scientists, he wondered, focusing attention, as they did with other diseases, on the outliers: the ones who didn’t succumb? Eventually, he heard that Paxton, at the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center, was looking for “nonprogressors”; Steve was, says Paxton, the first through the door. And very quickly his hypothesis was confirmed. Despite bombarding his CD4 immune cells with doses of HIV 3,000 times greater than usual, Paxton could not establish an infection.

The reason would take another two years to untangle. Like about 0.1 percent of people worldwide, Steve had inherited two copies of a genetic mutation called Delta 32. As a result, his CD4 cells lacked a working version of one of the two surface receptors that HIV must find and “unlock” to gain access to the cell’s machinery. Without that receptor, called CCR5, HIV just floats by and is cleared from the bloodstream within hours. Though Steve hated when people professed to feel “blessed”—it sounded, he said, so narcissistic—his defect was, in fact, a blessing. Or at least he hoped it would be for his sisters, who would never have to lose him in the way he’d lost so many.

For the Diamond Center, Steve’s combination of garrulousness and candor made him a perfect media tool. To help get attention and raise funds for ongoing studies, he told and retold the story of Jerry and the 70 (or was it now 80?) dead friends; he trotted out perfectly anodyne phrases to help locate AIDS research in the philanthropic mainstream. “In some very small way your life has given something back,” he said in an interview, as if speaking of someone else. “And this may affect the welfare and well-being of millions of people.” It wasn’t just wishful thinking. Understanding the role played by CCR5 has led to the development of the drug maraviroc, which was approved for use in 2007. Under the brand name Selzentry, it is now part of a standard protocol for many HIV patients and is undergoing testing as a prevention as well.

The attention his blood brought him was, at first, a comfort. Fielding media requests from all over the world, he felt he was honoring his dead friends’ memory. Perhaps he was also honoring his own desire for attention. He was the obvious star of the 1999 Nova documentary, which featured him in various stagy vignettes: sitting at his kitchen table with a pair of candlesticks, working on the AIDS quilt, deftly painting a watercolor. Though often dour, he mustered a smile while saying that if he could be useful to further research, “I’m here for that.” By 2002, when he appeared in an episode of a lurid series called Secrets of the Dead, he was fully comfortable in the role of science warrior: someone who had offered his body, which death would not take, to medicine, making a contribution perhaps like the one made by Great-uncle Burrill.

But fame was another infection his system quickly cleared. He tired of the media attention, which paled in comparison to that of real friends.

More than a hundred miles up the river from Manhattan sits the hamlet of Malden-on-Hudson. In 2006, Steve moved to a first-floor apartment carved from a once-grand three-story manor there. Inside, the three-room space was big enough to be both home and studio, but the two aspects were barely segregated. Art was everywhere. So was Steve. At 60, he settled into the easy new friendships of an everyone-knows-you community, involving himself with all its doings: the library, the studio tour, the Board of Elections. Many of his new acquaintances mistakenly thought, from his style and aura of noblesse oblige, that he was a millionaire. But he was just happy. Or, finally, happier. The place was another Utopia: a Brigadoon, he said without irony. And like Brigadoon, it soon disappeared. In 2012, the building’s owners, feeling the need to deal with its advanced state of disrepair, asked the tenants to leave.

Just as adulthood has a way of pushing normals toward deeper normalcy, it pushes eccentrics further toward the margin if there’s no countervailing force. Steve had friends, most of them at a distance, and a big blended family of half-siblings, step-cousins, and other less identifiable relations. But he had no spouse or children (though he’d wanted both) and, disastrously, no cohort. Survivor guilt he could work on, with therapy and visualizations and visits to ashrams. But surviving was a harder problem. It meant facing mortality, in essence, alone. And so, though AIDS bypassed him, the ordinary indignities of aging (a bit of neuropathy, a bout of arrhythmia) threw him into tailspins. He’d panic over nothing, complain about how old he was to people even older. When he needed his gallbladder out and Amy, with two kids at home, was unable to help him the way he’d helped her through her medical crises, he lashed out in a rage so severe it estranged them almost to the end of his life. The lovable eccentric had somehow become, Carla saw sadly, a stodgy old man. It wasn’t guilt that caused the change; it was disappointment. The world with all its marvelous places was nevertheless riddled with errors. It was not good enough.

After the semi-grandeur of Malden-on-Hudson, the dinky frame house in Catskill was a terrible comedown; anyway, the many steps to the bedroom were too many to climb. So after a year, he ended the lease, in June 2013. He booked a month, on scholarship, at the Ananda ashram in Monroe, where he hoped to repair his health and attitude while studying Sanskrit. Then, starting in mid-July, he would travel to London and France. Despite all this, he sounded manic to his sisters. One evening, after a meal out, he fell asleep at the wheel coming back to the ashram. He wasn’t supposed to drink alcohol with his various medications.

The trip to Europe got cut short; he had no money for the France leg. But his patrons in London (who’d paid for the flight) reported him happy: He delivered their painting and, with their teenage daughter, made a soulful video singing “Let It Be.” When he returned to the States in late July, having nowhere else to go while he looked for housing, he camped at the apartment of an old Hell’s Kitchen friend who spent summers away. He’d stayed there often enough to know the rule: He’d have to be out by the time his friend returned on August 26. The friend wasn’t looking for a roommate.

On Thursday, August 15, Steve finished his work on the Fodor’s guides to Aruba and Turks and Caicos, places he’d never get to. For the next week, he looked and looked, online and in person, but could not find an affordable apartment he liked near Malden—not even in dreaded senior housing. Perhaps when the “horse people” left in September the market would loosen, but he didn’t have that long. Of course, there was his generous Crohn cousin Ruth on the Upper East Side, who’d housed him in the past; but she was nearly 100 and he had a cold, so he wouldn’t ask. The trap was closing: “A map of the world that does not include Utopia,” Wilde wrote, “is not worth even glancing at.” Still, Steve tried to preserve an air of buoyancy. He had lunch with friends, spoke to family, and emailed widely, telling some people he was exhausted and numb but others that everything was, or would soon be, fine. In fact, on Tuesday, August 20, he let Carla know he’d be driving upstate that weekend to look for a new apartment. After that, when she tried to call him, his message box was full.

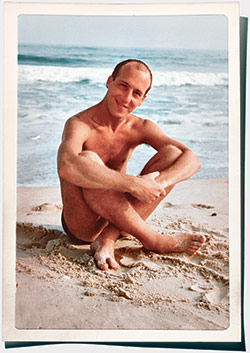

He didn’t drive upstate as planned, but in an email to an old friend Friday morning, seeming to refer to the housing problem, wrote that “something should break this weekend.” How he spent the rest of his last day is not known. How he ended it is. At 10:09 in the evening, according to his computer’s history, he called up a photo of himself at a beach, looking tan and happy, wearing colorful shorts. If he hadn’t before, he now took off his mother’s ring. With his 67th birthday 13 days away, he would not, after all, outlive her.

Someone called the police at 6:45 the next morning. An unconscious and unresponsive man was in the driver’s seat of a red Chevrolet Equinox parked in front of the Manor Community Church on West 26th Street in Chelsea. Emergency medical technicians pronounced him dead at the scene. The medical examiner’s office later said the cause of death was “acute intoxication due to the combined effects of oxycodone and benzodiazepines”; apparently he had stockpiled painkillers and tranquilizers. The manner of death—differentiated from an accidental overdose by the huge number of pills he swallowed—was suicide.

And so the friend who returned to the city two days later would not be stuck with a roommate. (Or a roommate’s things: Everything not in storage was crammed into the car.) But the rest of Steve’s friends and family would have the burden of living with him for the rest of their lives. Could they have done more? (But he hadn’t asked.) Should they have guessed? (But he hid his despair, if it was despair.) Was he ill? (An autopsy revealed nothing unusual in a 66-year-old man.) Had he really killed himself, then, over a housing problem? That seemed impossible; rather, a feeling gradually developed among the survivors that the suicide was a logically thought-out solution to problems Steve was simply tired of facing. Certainly the two-page note he left was not irrational. Mostly it provided practical information about things like his storage units and safe-deposit boxes, along with instructions to tell the Ulster County Board of Elections that he would not be a poll watcher come September. In any case, he died, unlike so many of his friends, at a time and in a manner of his own choosing. And, who knows, as a person who believed in an afterlife, he may have expected to be reunited with his mother, next to whom he is now buried; reunited with Jerry, gone these 30 years; reunited with all the others he loved and, because of a flaw, outlived.

Over time, his sisters have provisionally come to see evidence for this less tragic view not only in his birthday message to Amy (“enjoy gift”) but in the way he was found in the car by the police. With the seat reclined as far as it could go and a CD of Buddhist chants nearby, he’d propped his feet up on the dashboard. He was smiling.