Photographs: From left, courtesy of Santiago Calatrava; Christian Witkin

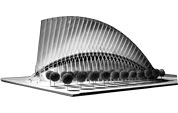

One day, when Santiago Calatrava’s skeletal, birdlike train station, with its oval body, white steel ribs, and raised wings, finally materializes into the World Trade Center Transportation Hub, the rest of lower Manhattan will come to seem blocky and stolid. Perhaps by then the gods of real estate will have willed into construction the magnificently fragile-looking high-rise that Calatrava has designed for 80 South Street—a stack of four-story townhouses clinging to a central core like monkeys on a bamboo rod. And maybe, just maybe, the architect will have moved closer to his fantasy of festooning New York’s public-transit system with gorgeous stations capable of galvanizing the neighborhoods around them.

“I’ve seen completely lost and abandoned sites, such as an obsolete oil refinery in Lisbon, become some of the most elegant areas of a city,” he says. He imagines urbane centers springing up around beautiful junctions in Jamaica and Hoboken, New Jersey, and a place he calls “New Jersey City.”

The Spain native Calatrava, who was trained as both architect and engineer and also makes sculptures and drawings, brings structural daring and metaphoric flamboyance to a city that does not generally trust extravagance in architecture. So for now, Calatrava’s New York remains an imaginary town, though a glance around the world makes it easy to be optimistic about the work he could do in his adopted city. In Seville, he threw a harplike bridge across the Guadalquivir River, which prompts dreams of another Hudson River crossing (a project he recognizes would be bad for Manhattan traffic). His first American project, an addition to the Milwaukee Art Museum that opened in 2001, is a wild flourish of a structure that resembles both ship and whale, as if illustrating the final battle in Moby-Dick. In Chicago, he is building a slender apartment tower that will eventually corkscrew 2,000 feet into the air: “We’re a long way from having exhausted the possibilities of the skyscraper!” he says.

These joyously kinetic forms have a way of seducing both traditionalists and novelty-seekers, because even as they plunge into the thrills of extreme engineering, they recall the bleached remnants of antiquity. His slung bridges and swooping stations embrace the modern mythology of speed, but they also have the weirdly organic look of prehistoric beasts.

For a man who spends his time inventing such bony, dancing forms, Calatrava has installed himself in an oddly staid patch of Park Avenue, surrounded by polished stone. With its reverberant, sparsely furnished halls, the townhouse where he maintains his studio (next door to the townhouse where he lives) exudes a slightly imperial atmosphere. The only soft thing around is Tiberius, the architect’s impeccably designed golden retriever, who lies, quietly shedding, on the marble floor. Calatrava opened this New York office last year, three years after moving his family here—from Zurich, which helps explain why to him even Park Avenue feels like a hotbed of creative ferment.

When his thoughts turn to 80 South Street, his expression grows wistful. “I hope it will get built,” he muses. Rising above the East River, within sight of the financial district and the Brooklyn Bridge, the building would be a Whitmanesque affirmation of New York optimism. Calatrava has been speaking for an hour in intricately wrought Castilian, but here he switches into hortative English. This is what his tower would prove: “You can go beyond!”

Profession: Architect

Peak: 1990 to Future

Essential Design: WTC Transportation Hub

(Photo: Courtesy of Santiago Calatrava)

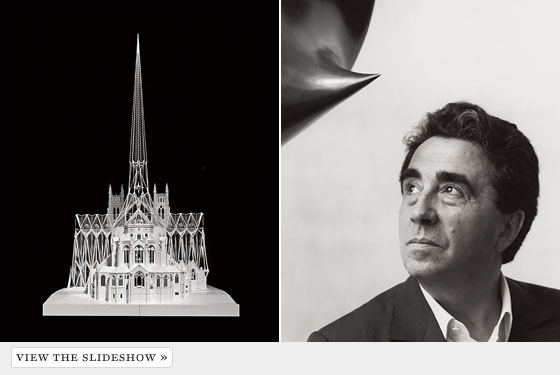

Proposal for Cathedral of St. John the Divine Although it was never built, Calatrava’s 1991 proposal for completing the Cathedral odf St. John the Divine, which included a glass-enclosed garden atop the nave, represented the architect’s first engagement with New York. All images courtesy of Santiago Calatrava