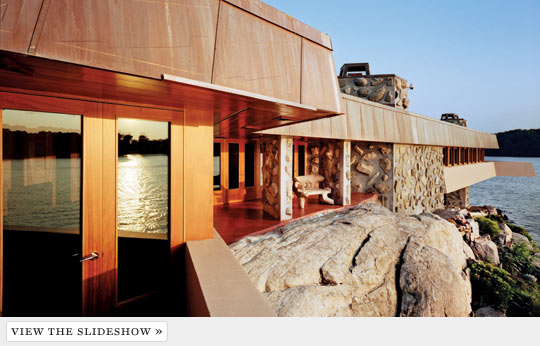

Photographs by David Allee

In 1950, at 83, Frank Lloyd Wright designed a house for a private island on Lake Mahopac, about 50 miles north of New York City. He dreamed it might surpass Fallingwater, his 1935 masterpiece—but then the client ran short of funds, and the house was shelved for almost 50 years. Now, after eight years of planning and construction, the house is finally complete—5,000 spectacular square feet of mahogany, lake stone, hand-troweled cement, and triangular skylights.

But no house, least of all a posthumous construction from the twentieth century’s most famous architect, is an island, and this one has become a particularly hot piece of intellectual real estate. There are those who celebrate its realization: It’s used in the packaging of the Apple-based architecture software that helped bring the design to life and is the subject of an upcoming PBS documentary. And there are its haters: architects, scholars, and amateurs who say it’s not Wright’s real vision—the stones jut too much, the skylights should be flat, not domed, and so on. As it stands, the house is officially unofficial. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation’s chief executive officer, Philip Allsopp, states bluntly, “It’s not a Frank Lloyd Wright house, because it hasn’t been certified by the foundation.”

Which means exactly nothing to Joseph Massaro, the locally born former sheet-metal magnate whose determination produced this house. He bought Petra Island on Lake Mahopac in 1991 intending to restore the guest cottage that already existed (also a Wright design, it was built in the fifties as a smaller project when the original client, A. K. Chahroudi, backed away from the big house). Massaro wrote to the foundation and obtained renderings of Wright’s plans for the big house in 1999 through its Legacy program, which then existed to enable people to realize never-completed Wright blueprints. Talks broke down over the foundation’s fee, which Massaro says was too high. In a telling side note, Allsopp put the Legacy program on hold last year.

The foundation debacle only fueled Massaro’s ambitions. He got detailed drawings from Chahroudi’s son and hired the prominent Wright scholar and architect Thomas A. Heinz to oversee the project. “This is Frank Lloyd Wright’s greatest house,” Massaro boasts. “Whatever we call it now, in 30, 40, 50 years, it’s going to be a Frank Lloyd Wright house—nothing anyone can do about it.”

Petra Island is an amazing house by any standards, and undeniably Wrightian, with dramatic, long cantilevers and the integration of outdoors and indoors. The house’s massive concrete slab shoots out 78 feet from the single, huge rock, stretching over a single column and out over the lake like the entrance to a James Bond villain’s compound. Visitors are ferried over by Massaro from his very un-Wrightian main residence on the lake’s south side (the Petra Island house is largely a summer getaway). An oxblood-red concrete stairway leads from the dock to a main terrace paved in giant triangles in the same oxblood concrete, broken by portions of “Whale Rock,” a giant granite hunk of the island that’s both foundation and dramatic décor. A small, dark entry opens onto the house’s money shot, a soaring fifteen-foot entry, with more oxblood triangles underfoot (hand-troweled for smoothness). One wall is a giant piece of the whale. Overhead are 26 triangular skylights—1,500 square feet—set in a concrete grid. The cantilevered gallery juts south, giving views of the lake to the east and west as the sun passes overhead. At the end of the gallery is the prow of the house itself, a porch originally designed with another set of stairs leading down to the rocks below. That was one of a handful of touches from the original design Massaro says were impossible to execute because of modern building codes.

The bedrooms and bathrooms are luxurious but typically small. “Wright wanted to get everyone out of the bedrooms and into the living areas,” says Massaro, adding that if he’d wanted to bastardize the original design, he’d have put in bigger bedrooms and baths.

“I went to every effort to make sure this was just as Wright designed it,” he says. From custom-making machinery to create the Wright-designed bas-relief copper panels that line the eaves of the house, to scouring the Internet and every other resource available to the modern obsessive (chimney caps and mahogany doors in Chicago, skylights from Santa Ana, California, the Connecticut craftsman who did all the Wright-designed doors, windows, and furniture), Massaro was intent on making a perfect Wright house. “We even had to buy a special die to cut the V-groove in the ceilings, because Wright’s V is a special size. That’s how far we went.”

Heinz tried numerous computer-modeling programs for more than a year before he found the ArchiCAD software program, which allowed him to conceptualize Wright’s roughly sketched plans in three dimensions in a way that felt comfortable and correct. Massaro’s contractor, Lidia Wusatowska-Leighton of C&L General Construction, toiled for months to get exactly the right consistency of concrete in order to create the mammoth grid holding the aforementioned skylights in a single pour. She also devised ingenious ways to get tons of materials and equipment to the island, like towing half-barrels of sand and gravel over three-foot-thick ice in winter.

The efforts show. The house reads in many ways as an exemplar of Wright’s mid-century style, when he was experimenting with triangles and hexagons as key elements of a new geometry. “He was at the zenith of his fame,” said Alan Hess, the author of Frank Lloyd Wright: Mid-Century Modern Houses, due out in October from Rizzoli. “He did more buildings in 1951 than he’d ever done before, and he was starting to go to greater extremes than ever before.”

Although its owner is riding the euphoria of finishing a bona fide showplace, the Petra Island house isn’t going to challenge Fallingwater as Wright’s domestic masterpiece. But it’s no slouch, either. “It’s one of Wright’s most dramatic efforts, right up there with Fallingwater,” says Robert Twombly, an architectural historian who has written a biography of Wright and is duly impressed with Massaro’s sincerity and Heinz’s scholarship. “To me the scale is too big,” he admits. “I feel a bit dwarfed, but it still shows that Wright could create a stunningly beautiful house.”

People can, and will, argue whether Wright himself would have been pleased with what’s now up on Petra Island. But given how much he loved attention and controversy, it’s a good bet the hubbub alone would have thrilled him.