Isaac Mizrahi and Maira Kalman live in the same Greenwich Village building and have been the best of friends since 1990. They sat down in her apartment for a chat about taste, memory, and Kalman’s mother.

Isaac Mizrahi: I think of you as a kind of arbiter, a touchstone. If you put Maira next to anything in the world, she can say whether it’s good or not.

Maira Kalman: And she’ll regret it.

Who was your biggest influence?

My mother was the influence on me—my father was absent. He was a diamond dealer; he was doing wonderful things in the background, and women were left at home. So my mother really was in charge of everything: the ballet, dance lessons, piano lessons, and latkes.

Do you think you are becoming your mother in some strange way?

You know, it’s funny that you say that, because I find that I am consciously trying to move like she did, and I am also wearing her bracelet. So I see that with my hand I am doing things, like when I cook, which is never …

She was a good cook?

She was a great cook, and she would take her shirt off when she cooked, so she would fry in a bra. She had this gigantic bra [Mizrahi laughs] and a little camisole, and she would tuck the kitchen towel into her bra and fry.

I mean, rather than ruin a shirt. Why ruin a shirt?

She always wore white.

Tell me about the apartment your family still owns in Tel Aviv, and what it was like to be young there.

Tel Aviv was light and the beach, fluttering awnings, the sun. White—there was this whiteness, it was a white city. Our apartment still is.

Is it a Bauhaus building?

The apartment isn’t Bauhaus, but it’s very plain, very pared down. It’s got terrazzo floors and tiles on the walls in the kitchen and bathroom. And we sit on the terrace and watch everybody walk by.

What’s your favorite room in the apartment?

The kitchen, and the cabinets are called Golda, after Golda Meir.

Who named the kitchen cabinets after her? The company that made them? Or you?

Not me and not the company but somebody else—we don’t know who.

After Tel Aviv you moved to Riverdale?

No, then we moved to a hotel on the Upper West Side.

How old were you?

I was 4. So we came from sandy, sunny, family, honey-cake white to crazy city: gray, concrete, pizza, hamburgers.

Did you like it?

I loved it. I was just happy. I was a happy kid. So we moved into the hotel where the furniture was very fragile and spindly, and the TV was brought into the room and it was gigantic. There was unlimited watching, because who knew that it wasn’t a good thing to do? And then we moved to Riverdale: bucolic running around on a bike. And there was Loehmann’s.

Say no more! And did you work a little magic on the Riverdale place?

Well, I didn’t do anything, I was just, you know, wandering around there. I was a kid. I think we probably had hand-me-down furniture from our relatives. We had relatives who were very rich in Great Neck. They sent us stuff, and it was a hodgepodge. But then my mother started to subscribe to Vogue and Realities and Life magazines, and all of a sudden the world opened; all of a sudden we were looking at things that were amazing. And then we did our Europe trip, and we went to the Excelsior hotel in Rome, and that was also a revelation, and we started seeing things and going to museums, so it was an education.

Do you think that Sara Berman, your mother, understood aesthetics and design principles on the same level as you do?

No, no. I think that she just wanted to have nice things around her. But she also never spoke very much. She was a wonderful mother in amazing ways, but we never had conversations about things. You know, I have no idea what she thought of anything. It was more like, Pass the salt.

Where do you think you got such a sensibility about … objects?

Well, my sister is an artist and an interior designer. She went to high school for art. I went to high school for music. But then it was in the air, it was all around us. And then it was meeting [Maira’s late husband the designer] Tibor and graphic design, so that whole world opened up, kind of from nowhere.

And what made you so opinionated, so definite, about things?

The theatre [in an English accent, laughing].

Really?!

No. You know how things are just incomprehensible, and then they happen, and you wonder, Well, why did that happen? And I always saw myself in the third person—I had a vision of myself. The same way that I always had a vision of myself as a writer and I had a vision of myself that I could draw—it just came from some undefined place.

In terms of my upbringing, I always think about the fact that we had this olive-green carpeting throughout the whole house on the first floor—it was beautiful—and for years in my bedroom, I had the same carpet, like, literally the same rug.

As an adult?

As an adult. And I didn’t put it together until my sisters came over and said, “What?!” Are there things in your apartment like that?

I think the light in Tel Aviv informs the desire to have light in this space. I think maybe there was something also about clarity, that if there was a goal it would be to only have things around you that you really care about.

You said that you fell in love with this apartment at first sight. Why?

I fell in love with the block because there is something about the light on this street. And some places make you feel good: This is home. And other places make you feel despair—you know, How will I ever get out of here?! Tibor and I had one apartment once, and we spent one night, and I said, “We are out of here!”

And there is something about the basic bones of this building—something weirdly Art Deco in a not-hideous way. And something nautical—like we are on a ship. And it always feels like Fred Astaire might be in the next room. I don’t know why.

’Cause we are only watching Fred Astaire movies in this building; it’s in the lease.

I have been around you for many years in this apartment, and I notice that it changes a lot.

A ladder goes in, a ladder goes out. I don’t like anything permanent, I have to be able to flee. You have to be able to flee at a moment’s notice [laughing].

The apartment’s like a laboratory or something. How would you describe it?

Actually, it’s very … I love that idea. It would be pretentious to say Bauhaus, but, there, I said it. But it would be like some kind of school where you keep changing things. Or an exhibit. I feel like this apartment is like that to me: a different kind of exhibit each time, and weirdly it feels like it is lit. Like that suit of Toscanini’s is lit, but it’s not. I think if I had a shop, it would change every day.

You got that suit at a Doyle auction, right?

One person was bidding against me; my heart was beating so much that everybody around me thought that something horrible would happen if I didn’t win, so I paid $800. And now he hangs in the room and I talk to the jacket all the time, thinking of people [who have touched it]. There are a lot of people here in the room with me.

There is a lot of DNA on that jacket. Which object in this apartment do you like the best? Which means the most to you?

I still do have the little lunch bag that my mother made out of a towel and embroidered with my name on it for when I went to kindergarten. And it’s this big. I think she gave me five sandwiches and three apples, it’s huge! But if I had to choose one thing that I love, there is nothing. I am very sad to think about having stuff, and not having stuff. There is a sense about wanting to have nothing, and then there is a sense about having everything and not giving anybody anything and keeping it all. But the things that I have keep changing and go into different rooms. It is always a conflict.

Is it a commitment thing, the fact that you change so much?

In the I regret everything I say mode? [Laughs.] I regret everything I do.

Yes.

I regret everything: nice “up” ending for our talk!

But does it come from a joyous place when you choose things, or does it come from a critical, mean place?

I think it is like starting fresh. Every Monday morning is new hope. And I just like the idea that the set changes. It is a set. That is my home.

Sara Berman, Maira Kalman’s mother.

“My mother was the influence on me.”

Photo: Courtesy of Maira Kalman

Tel Aviv

“The kitchen, and the cabinets are called Golda, after Golda Meir.”

Photo: Courtesy of Maira Kalman

New York

Kalman’s Village apartment, a “cabinet of curiosities” (including the suit worn by Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini).

Photo: Thomas Loof for New York Magazine

Kalman’s Village apartment

Photo: Thomas Loof for New York Magazine

The Meaning of a Dream

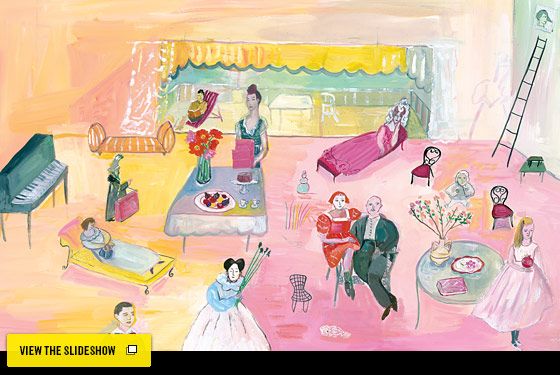

The room Kalman drew for us is filled with a cast of characters and objects that includes Proust1 (“He talks a great deal about objects and rooms and the people in the rooms and the emotions in the people in the rooms”); The Countess of Castiglione2; her sister’s granddaughter, Bella3; Charlotte Salomon4 sitting on her father’s lap in Berlin (she “is a painter who is very important in my life. She did

a series of gouaches with text about her crazy family. She was killed in a concentration camp in her twenties, but the paintings survived”); her son’s girlfriend, Alexandra5; a Bertoia chair6 (“Just the most simple, smart, un-self-conscious chair. The MoMA garden uses it, and I have written many books sitting in the “garden”); and Maira7 herself, on a chaise, dreaming about all of this.

Photo: Painting by Maira Kalman