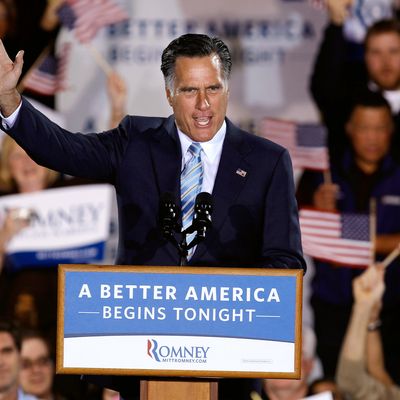

Mitt Romney delivered a new version of his speech last night. The main argument is very, very simple: The economy has been bad since 2009, and voters should blame President Obama. This is almost certainly the correct strategy for Romney, yet it requires him to craft a case that neither he nor his party actually believes.

The guts of the speech are mainly an endless litany of economic suffering. That Obama is to blame for this state of affairs is Romney’s premise, not his argument.

Romney does argue that the election should, morally speaking, center around the state of the economy. He sets up what he defines as the proper test of success for Obama: Are you better off than you were before he took office? “If the answer were ‘yes’ to those questions,” he says, “then President Obama would be running for reelection based on his achievements … and rightly so.”

But the answer is no. Therefore, accuses Romney, Obama is running “a campaign of diversions, distractions, and distortions.”

When Romney offers his high-minded account of what the election should be about, note that he does not really present this as a contest of ideas. He doesn’t even hint at a theory as to what sort of economic response would have better insulated the country from the economic shock. More austerity? Different, or bigger, stimulus? We have no idea. This is probably because some of Romney’s closest advisers are advocates of Keynesian economic theory, while the bulk of the Republican Party has lurched toward hoary Austrian economic doctrines insisting that inflation is the true threat and massive short-term pain the solution.

I’m sure Romney’s advisers think they can craft better short-term macroeconomic policies. Possibly they’re right. (I actually think they may be — Republicans will probably return to supporting Keynesian economics once their president’s neck is on the economic line, as they did when George W. Bush was president.) But the point is that Romney is not running on a plan that his advisers think of as a plausible program of short-term management. He doesn’t want to campaign on that. He simply wants to campaign on the straightforward economic impulse: The economy has been bad under Obama, vote Obama out.

Now, it is certainly true that voters do usually evaluate incumbents based on the state of the economy. This is not entirely irrational — some parties do a better job of managing macroeconomic fluctuations than others. The British government imposed the austerity agenda that American conservatives have called for and, as a result, have slid back into recession, and seen their polls fall as a result.

But the process is mostly irrational. Political scientists have found that voters base their economic judgments of the incumbents on very short-term measures. The timing of the business cycle matters far more than the wisdom of the incumbent’s policies. In the current crisis, voters across the world are turning against incumbent parties of left, right, and center, simply because it’s quite difficult to actually create prosperity against the backdrop of a global economic crisis.

Larry Bartels, in a famous 2008 paper, explained the deep irrationality undergirding the way voters overreact to the state of the economy when voting:

In the United States, voters replaced Republicans with Democrats in 1932 and the economy improved. In Britain and Australia, voters replaced Labor governments with conservatives and the economy improved. In Sweden, voters replaced Conservatives with Liberals, then with Social Democrats, and the economy improved. In the Canadian agricultural province of Saskatchewan, voters replaced Conservatives with Socialists and the economy improved. In the adjacent agricultural province of Alberta, voters replaced a socialist party with a right-leaning party created from scratch by a charismatic radio preacher peddling a flighty share-the-wealth scheme, and the economy improved. In Weimar Germany, where economic distress was deeper and longer lasting, voters rejected all of the mainstream parties, the Nazis seized power, and the economy improved. In every case, the party that happened to be in power when the Depression eased went on to dominate politics for a decade or more thereafter. It seems far-fetched to imagine that all these contradictory shifts represented well-considered ideological conversions. A more parsimonious interpretation is that voters simply — and simple-mindedly — rewarded whoever happened to be in power when things got better.

The irrationality at work is that voters apportion a huge share of credit and blame to ruling parties for factors that lay mostly — not entirely, but mostly — out of their control. What’s more, they vote on macroeconomic conditions, but what they get is a whole host of additional policies along with it that often have no relationship at all to the cause of their vote. Indeed, that is exactly what Romney hopes to accomplish. He wants to leverage short-term discontent based on the global economic crisis into an opportunity for Republicans to impose long-term changes to American government. This is sort of a trick, though it’s a trick both parties are happy to play. (Rahm Emmanuel: “Never let a serious crisis go to waste.”)

Romney, in his speech, frames the notion of voting on the state of the economy as a discerning judgment: “It’s still about the economy … and we’re not stupid.” It sounds like an appeal to intelligence, but it’s not the kind of appeal Romney, or any member of Romney’s inner circle, would make to a person they consider intelligent. If they had to persuade a smart, well-informed person who understands American politics to vote for them, they would not hinge their argument on the fact that unemployment or gas prices are higher now than they were in October 2008. They don’t really think that long-term questions like whether the federal government has a responsibility to provide health insurance for all citizens should rest on how rapidly personal income grew in the second quarter of 2012.

As it happens, most persuadable voters lack much information about politics or policy, and tend to vote like that. It’s a true but regrettable fact of democracy. I don’t blame Romney for taking advantage of it, the way candidates in all parties everywhere do. But voting on the economy in the way Romney is urging voters to do is, in fact, stupid.

What does Romney truly think the election is about? That’s in his speech, too, though more obliquely. I’ll get to that in a follow-up post soon.