The improving economy has forced Mitt Romney’s campaign to stop assuming that voters will take the lousy economy as a given, and begin making an argument about it. The argument, specifically: Sure, we’re recovering. But we’re recovering more slowly than we should.

Former Bush advisor Ed Lazear makes this case in the Wall Street Journal today. Lazear compares the recovery to previous economic recoveries, and finds we’re growing more slowly. Lazear’s compares the current recovery to — no, not the nineties, that would lead to awkward questions about why we can’t restore Clinton-era tax rates — how about the eighties?

In the early 1980s, the economy experienced a double-dip recession, with contractions in both 1980 and ‘82. But growth rates in the subsequent two years averaged almost 6 percent. The high growth that persisted throughout the 1980s brought the economy quickly back to the trend line. Unlike the current period, from 1983 on, the economy was in rapid catch-up mode and eventually regained all that had been lost during the early ’80s.

You can probably guess why Lazear thinks we grew faster after the 1982 recession than after the 2008 recession: socialism. (Or, in Republicanomic-speak, “Threats of higher taxes, the constantly increasing regulatory burden, the failure to pursue an aggressive trade policy that will open markets to U.S. exports, and the enormous increase in government spending all are growth impediments.”)

In a fortunate coincidence of timing, Bloomberg News has an op-ed today by Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff rebutting this new Republican line. Reinhardt and Rogoff were, until very recently at least, economists in good standing on the right. Their book This Time Is Different was not written to discredit Mitt Romney’s stump speech — it was written several years before — but it might as well have been. Their fundamental argument is that financial crises are very different than ordinary recessions, and almost invariably produce deeper crashes and slower recoveries. They are incredulous that anybody is trying to argue otherwise:

After a normal recession (which for the average post-World War II experience in the U.S. lasted less than a year), the economy quickly snaps back; within a year or two, it not only recovers lost ground but also returns to trend.

After systemic financial crises, however, economies of the postwar era have needed an average of four and half years just to reach the same per capita gross domestic product they had when the crisis started. We find that, on average, unemployment rates take a similar time frame to hit bottom and housing prices take even longer. With the Great Depression of the 1930s, economies on average needed more than a full decade to regain the initial per capita GDP.

“After the Fall,” a 2010 paper written by one of the authors of this article and Vincent Reinhart, a former Fed official who is now chief U.S. economist at Morgan Stanley, added evidence that in 10 of 15 severe post-WWII financial crises, unemployment didn’t return to pre-crisis levels even after a decade. It also showed that in seven of the 15 crises there were “double dips” in output.

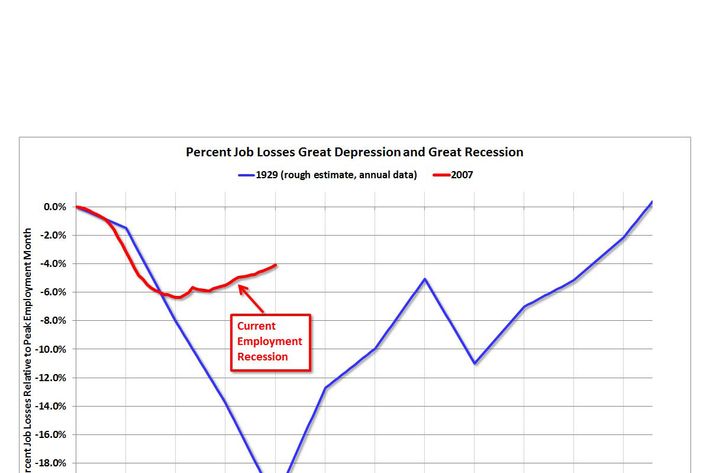

Lazear doesn’t really have an answer here. He points out, correctly, that the Great Depression was also a financial crisis, and it had fast growth after the crash:

The Great Depression also began with a financial crisis but saw high growth rates following contractionary years, and the output lost in negative years was eventually regained through higher subsequent growth.

Well, yeah. But the Great Depression saw a much deeper, much longer fall in the first place:

How on Earth can this comparison possibly sustain his claim that policy errors have made the current recovery weaker?

I’m familiar enough with the market at work here to understand that if the dynamics of the campaign demand arguments that we’re undergoing an unusually weak recovery by the standards of a financial crisis, then some party-affiliated economists will supply them. But this can’t be the best the GOP has to offer.