Last week, the Obama reelection campaign told Mark Halperin that it believes Mitt Romney’s one chance of winning the election would be to establish himself as a credible economic fix-it figure, and that it intended to focus its attacks on destroying that reputation. Today the campaign launches a missile straight at its target with an unusually long two-minute campaign ad assailing Romney’s tenure at Bain Capital, along with a website (romneyeconomics.com) reinforcing the message that Romney’s record is all about extracting profit for the very rich, at the expense of the middle class. The name of the website, of course, implies that Romney’s record at Bain defines his economic philosophy.

Last fall, Ben Wallace-Wells wrote a fantastic cover story making the case that Bain does indeed represent the epitome of Romney’s economic philosophy. That piece was, obviously, far more balanced and thorough than Obama’s attack ads. It tells the story of how Bain Capital helped remake American business, weeding out inefficiencies and finding hidden reserves of profit. The story testifies to Romney’s skill as a capitalist, while also connecting his record with a reorientation of American capitalism toward both higher productivity and higher inequality.

One of the hidden reserves of profit discovered by Bain was the moneymaking potential opened up by breaking a social compact between workers and their bosses, a compact that increased the security of working life but held down the profit potential of those who owned and managed the businesses. The old corporate ethos was well embodied by George Romney, a corporate titan turned liberal Republican governor, who as head of American Motors repeatedly turned down bonuses because he believed $225,000 a year (about a million and a half dollars today) was the highest salary an executive ought to earn.

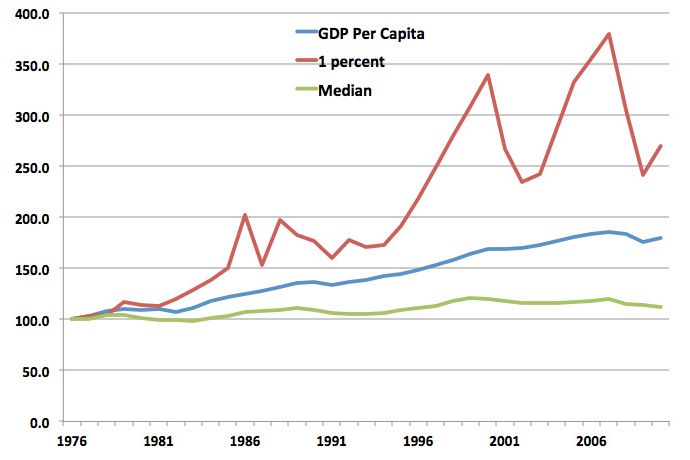

The breakdown of that ethos, and the unleashing of a more pure form of capitalism, is a major factor is the rising tide of inequality that has prevailed over the last three decades. Matt O’Brien recently compiled a chart vividly displaying the diverging fortunes of the bulk of the American workforce against the spectacular rise at the top:

The blue line in the middle is the rise in GDP per capita since the mid-seventies. The green line below it is median income, which has been flat. The red line at the top is the income of the top one percent. The first-cut analysis of all this is that America has become a much richer place over a generation, but the entire increase in wealth has accrued to those at the top.

This is the backdrop for the larger philosophical debate undergirding the presidential campaign, and the larger fight between the two political parties. The Republican position is that the rise in inequality is perfectly fine, as it signals rising rewards accruing to those who have justly earned them. Conservatives have coalesced around the view that market incomes are inherently just. Romney himself has argued that to the extent that unfairness exists in the economy, it consists of intervention by the government or labor unions. The market is fair by definition.

Democrats are not proposing to roll back the staggering rise in income inequality, and they have no plan to restore George Romney–style capitalism. They do, however, believe that the diverging fortunes of the middle class and the ultra-rich offer more urgency to the case for a government that supports the unfortunate and extends opportunity to the middle class, and at the very least militates against the Republican plan to make the government far less redistributive. That is why Obama has, since December, been hammering home the theme of rising inequality, the role of government in mitigating it, and the ways the Republican program would exacerbate it.

Joe Scarborough’s sneering dismissal of Obama’s Bain attack as “demagogic” surely will signal the predominant reaction among the news media and the business elite. Obama’s ad is surely simplistic and one-sided. He has no proposal or intent to roll back Romney’s efficiency revolution. But it’s interesting to contrast the measured tone of Obama’s ads against the over-the-top style of the same material in the hands of Romney’s GOP rivals. Obama’s ad merely presents interviews and clippings from news articles. “King of Bain,” an anti-Romney documentary disseminated by supporters of Newt Gingrich earlier this year, is hilariously propagandistic, with grainy images of cigar-smoking men and fulminations against greed.

The panic Gingrich’s campaign inspired among Republican officials, not just those working for Romney, gives away the fact that this is a true political vulnerability for the Republican nominee. The transformation of American business is deeply unpopular. It has made working life less secure and has failed to deliver broad-based prosperity even while it has bestowed enormous riches on the most fortunate. The locus of public opinion on it in many crucial ways sits well to the left of what either party proposes. Many Americans want to go back to the days when corporations offered secure employment and generous benefits.

That’s why, interestingly, Romney is not trying to fight against the currents of public opinion but glide along with them. His response to Obama is telling. As reported by Byron York, Romney plans to hit back at Obama by citing the auto bailout, which imposed some of the same kinds of restructuring that Romney used at Bain: wage cuts for workers, incentive payments, and so on. The comparison is fairly silly, because the key point is that Romney’s career produced huge gains for owners of capital, and the auto bailout forced them to swallow huge losses. But it shows Romney’s recognition of what the voters want.