The other night, I flipped to a few minutes of Back to the Future — actually, it was the considerably worse sequel, centering on a dystopian alternative future in which Biff Tannen has gained wealth, power, and Marty McFly’s mom. I was struck by a recurrent plot fact that had never quite registered before: The local newspaper, the Hill Valley Telegraph, plays a major role in the plot exposition of both films. And the paper’s news judgment is exceedingly bizarre.

We are introduced to the Telegraph when Marty, having been transported without his knowledge to 1955, sees a headline reporting national news:

Marty is struck by the oddness of it because, despite having driven what he knows is a time machine, he has not figured out that it’s 1955. But the headline is useful because it establishes that the Telegraph is not merely a local paper — it reports on national news, albeit in a vague and uninformative fashion. A president can’t veto a “Senate bill,” he can only veto a bill that’s been passed by both houses. It’s not clear why a veto would merit a banner headline — normally reserved for declarations of war, presidential election, or assassinations and the like — but if it did, you would think the subject of the bill would make it somewhere into the headline.

The Telegraph’s strong (if not informed) interest in Washington legislative arcana makes it all the more striking that it proceeds to devote banner headlines to relatively minor developments impacting private citizens in the town, including a house fire:

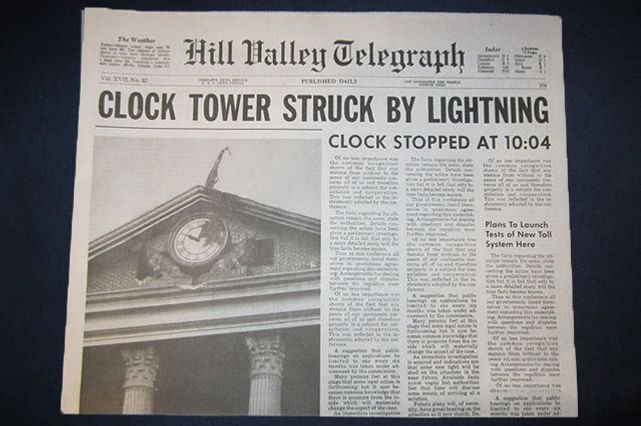

A lightning strike:

And the presumably insane ranting of a local farmer:

It is equally unclear why the Telegraph’s editors would devote such extensive space to Biff Tannen gambling coverage:

Obviously, the Tannen gambling beat would grow more important over time as he amassed larger and larger winnings through a suspiciously improbable winning streak, though why the paper would cover even his first wager so breathlessly is hard to explain.

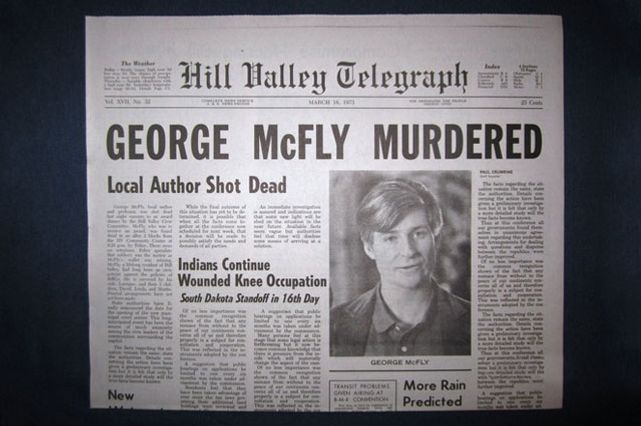

Likewise, maybe the Telegraph — especially in a dystopian, Tannen-controlled town — would have taken a sensationalist approach toward crime stories:

But banner headlines to announce that a local author of pulp sci-fi novels has won a book prize? And that a scientist of no known accomplishment has won a civic prize? That merits news above Richard Nixon brazenly violating the 22nd Amendment to seek a fifth presidential term?

Perhaps the strangest assumption in both movies is not only that the Telegraph would exhibit such odd news judgment, but that it would also nevertheless continue to publish in print well into 2015. Unless perhaps the film is trying to point to a different future for media: hyper, hyper-localism.