As you may have heard from the New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, or 8 billion tech blogs yesterday, Apple is talking with its suppliers about creating a curved-glass “watch-like device.” Presumably, this wrist computer would have many of the same features as an iPhone or an iPod mini, but at a fraction of the size. And it would be the first fully wearable Apple product (unless you’re the guy who got an iPod Nano implanted in his arm).

Many people think an Apple watch is a brilliant idea, since the Kickstarter-based Pebble watch got millions of dollars in funding, and since smart watches were all the rage at this year’s CES. (“Evidence is growing that this is the Next Big Thing in consumer tech,” Chris Ziegler writes at the Verge.) But before you throw out your Timex in anticipation, let’s take a trip down memory lane and remember the smartwatch’s rocky history.

The concept of a wristwatch computer originated in pop culture with the Dick Tracy comics of the forties. But the first actual commercial use of computer technology in watches had to wait until the early seventies, when Pulsar and other electronics companies began making calculator watches that could perform basic arithmetic functions. Then came gaming watches, which allowed people to play rudimentary one-handed video games on their wrists, followed by musical watches.

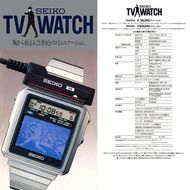

Smartwatches got incrementally more goofy-looking as the technology behind them became increasingly advanced. There was a 1982 attempt by Seiko to incorporate a miniature TV into a wristwatch, which was as technologically impressive as it was commercially unsuccessful. Seiko followed that up with the 1983 Data-2000, which came with an attached keypad and calculator.

In non-Seiko smartwatch efforts, there was the 1998 RuPuter, which had a DOS interface and 128K of RAM. And, in later years, the 2003 Fossil Wrist PDA, which used the Palm OS and had a miniature black-and-white screen. The Fossil PDA watch was hotly anticipated when it launched (Wired called it “revolutionary”) yet it garnered only “lukewarm” sales. Microsoft even tried to create its own smartwatch in 2003 — the SPOT watch — but dropped it several years later when it failed to sell.

These early smartwatches weren’t just novelty items cooked up by bored engineers; many big-name companies actually thought wrist-top computing would be the wave of the future. And yet, every one of them fizzled. Sales figures for most models aren’t readily available, but it’s safe to say that none heralded the kind of revolution its makers hoped for. The smartwatch with the best reviews and most marketing hype at launch — Fossil’s Palm OS watch — went on sale in 2005 with a $250 price tag, which then dropped to $200, then below $100, then was quietly discontinued within a year.

It’s tempting to blame ancient technology for the failure of early smartwatches. Certainly, an Apple-designed watch in 2014 or 2015 wouldn’t struggle with grainy resolution or bulky discomfort. But even with the best materials and technology available, there seem to be certain limitations to the form. A wristwatch, by its very nature, is fairly immobile (in that it stays on the wrist and can’t be manipulated like a tablet or phone), it can’t be large enough to function as a full-fledged replacement for either of those devices, and it has to be used entirely with one hand.

Nobody yet knows what Apple has planned for its watch — the Journal says only that it “would perform some functions of a smartphone” — but it’s likely that it would advance on the concept of the Pebble, which connects to phones via Bluetooth and acts as a sort of wrist-bound alert system. It might also combine some movement-tracking features of the Nike Fuelband or the Jawbone Up.

Of course, Apple will want to add something new and groundbreaking to its iWatch, but it’s unclear what it could try that nobody else has done before. The wrist-bound computer is among the most stifling design challenges in the personal tech world, and it’s not even clear that the payoff for solving it is all that large. A Morgan Stanley analyst (generously) estimates that an iWatch could generate between $10 and $15 billion in annual revenue for Apple, if 20 percent of all iTunes users buy it. That’s not chump change, but it’s not the kind of money that changes a company’s trajectory. (For comparison’s sake, the iPad did $10.7 billion in sales last quarter alone.)

Smartwatches are the jetpacks of personal computing, in that they’re a sort of futuristic, sci-fi-movie technology that people want badly in theory, but hardly clamor to buy when it’s actually introduced. And Apple CEO Tim Cook may discover that even if he can convince a significant chunk of Apple’s user base to wear an iWatch — defying decades of precedent — it won’t be the kind of revenue-generating monster the iPhone and iPad have become.

This morning, at a Goldman Sachs tech conference, Cook said, “Apple makes bold and ambitious bets on products.” But an iWatch is hardly bold or ambitious. It’s an attempt to join an emerging category as it heats up and steamroll smaller companies like Pebble. In the long view, it’s an attempt to succeed where lots of other companies have failed and build a product that will serve as, at most, an accessory to other Apple devices.

It’s a fallacy to say that companies can’t attempt audacious and mundane things at the same time. But every resource devoted to one major project is a resource diverted from another. Shouldn’t Apple spend its massive cash pile developing something truly daring and revolutionary — the kinds of things Google is attempting to do with wearable glasses and self-driving cars — and leave the computerized watch problem for others to chip away at?