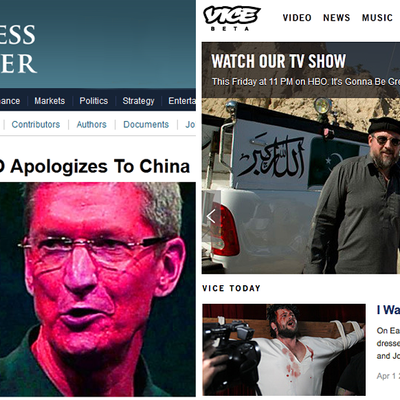

This week’s New Yorker, along with a brutal Yankees cover, comes with two massive media profiles on next-generation companies with nontraditional origin stories. In “The Bad-Boy Brand,” Lizzie Widdicombe takes on the foul-mouthed free-for-all of Vice Media, which just happens to basically print money at this point, having struck gold in online video and expanded in every direction — advertising, television, corporate sponsorship — as a capital-b Brand. As a chaser, Ken Auletta tells the story (subscription-only) of good old-fashioned blog Business Insider and its founder, former Wall Street bad boy Henry Blodget.

These being stories about journalism from a venerable old-media institution like The New Yorker, the bottom line is, unsurprisingly, trust. But these being stories about journalism, and the future of it, the bottom bottom line is money.

The theme of journalistic integrity runs through both articles after its star characters are presented as semi-unscrupulous and unorthodox. Vice, the still uninitiated will learn, used to be only about sex and drugs and poop:

The company started in Montreal, in the mid-nineties, as a free magazine with a reputation for provocation. Once, after its editors were accused of sexism for featuring nude porn stars in the magazine, they posed nude as well.

Shane Smith, the company’s CEO, used to be known as “Bullshitter Shane,” and “could sell rattlesnake boots to a rattlesnake.”

Blodget, meanwhile, was barred from Wall Street as the result of a 2003 settlement with the SEC, and still has that huckster’s air about him: “When he talks, his arms swing and his voice rises, conveying the enthusiasm of an evangelist.” Blodget, though, is more self-conscious of his outsider status, telling Auletta, “Ten years ago, I got what amounted to a dishonorable discharge from the industry, and I’ve always been ashamed of that. At some point, if it seems appropriate, I would like to explore the possibility of being reinstated.”

But both Vice and Business Insider found new life online, where, Blodget says, everything is “only a click away … The Internet has disrupted many industries. The newspaper business has been destroyed. It’s beginning to happen, arguably, to television. Consumer behavior is changing!” That’s what Vice is counting on, transitioning from print to video, expanding its documentary features from YouTube to CNN to HBO. (“I know it sounds crazy, but let’s say, hypothetically, you become the default source for news on YouTube. You get billions of video views, WPP monetizes it. Then you are the next CNN,” says Smith.)

But neither company has been completely accepted by the old guard. Here’s Steve Shepard, the dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York, on Blodget, who was called “scum,” “a boldfaced liar,” and a “dirtbag” when he started writing online:

“I don’t trust him, and I just can’t forgive him for his deceit. A lot of people suffered — lost jobs, lost income, lost pensions. Blodget wasn’t the only villain, or even the primary cause of the boom and bust, but he typified the worst of the excesses on Wall Street. Blodget was dishonest and deeply cynical. Journalists should be the opposite. It hurts me to see him ply our trade.”

[…] A senior Wall Street executive, asked if he trusted Blodget, said, “Of course not. This doesn’t mean he can’t have good ideas. But he’s a promoter.”

Somewhat ironically, the problem for Vice isn’t so much its debauched past — which comes with the cred ever-important with the male, 18–34 demo — as its corporate future, something Blodget, conveniently for this parellel reading, puts plainly in his profile: “Can you build a self-sustaining publication online, or does it have to be subsidized by Bloomberg or G.E.?” He’s not talking directly about Vice, but he might as well have been. Widdicombe writes:

To some, it’s the way Vice works with brands, rather than its reporting style, that makes its journalism suspect. […]

If you spend enough time inside the Vice empire, much of its noise and energy — the Web site and the ad network, the international offices, even Smith’s talk of global domination — can start to feel like a ruse, in the vein of its “basketball diplomacy” stunt, a show to make those partnerships happen.

On this point, Smith is defensive, and inadvertently provides a response to Blodget’s hypothetical: “Part of the reason Vice is successful is because we have cash to make stuff. Everyone else is just fucking wandering around trying to find budgets to make their dream project,” he says. “Anyone who is in the media game and says, ‘I don’t want to make money,’ is basically saying, ‘I don’t want to work. ‘Cause money makes media.”

Blodget and his team, on the other hand, make slideshows. The company lost $3 million in 2012, and expects to do $11 million in revenue this year; BI has spent $7 million of the $13 million in investment money it raised. Journalism, Blodget says, is “a bad business so far,” adding, “It’s tough to monetize.”

It’s not a one-to-one comparison, of course — Vice is a much older, international multimedia behemoth — but the contrasts are fascinating in light of the parallel narratives: Revenue for Vice last year was about $175 million, with profits of $40 million, and mostly from online video content. After some 14,000 words spread across both companies, one might conclude that the written word isn’t worth very much at all.