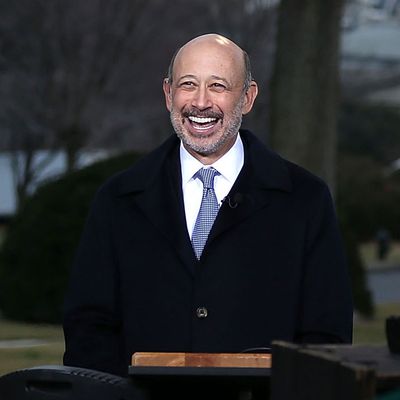

Last week, fuzzy-faced Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein cheered some graduating seniors at LaGuardia Community College by telling them that, with hard work and perseverance, they, too, could make it big. Today, Blankfein continued his streak of positivity by saying that the biggest problem with the economy — the thing truly holding America back — is that there are too many Negative Nancys gumming things up.

“Economy is not a science, it’s a social science,” Blankfein said at a Politico breakfast chat this morning, according to Business Insider. “A lot of good things are happening, but sentiment is so negative.” As a solution to the nation’s economic ills, Blankfein prescribed a steady diet of “less negative reporting and less negativity.”

Blankfein isn’t wrong that the business pages of major news publications can often resemble a Chicken Little convention — a tendency that can be frustrating at times. Rather than celebrating the recovery of the housing market when home prices began to rise, reporters immediately began crafting doomsaying narratives about a New Housing Bubble That Will Destroy Us All. Instead of celebrating improving jobs numbers and falling unemployment in a monthly jobs report, stories often single out the few negative elements of the report. If the global economy were a basketball team, much of the business press would be a coach who spends the entire game screaming at his players, even when his team has a 30-point lead.

Partly, this is because of the incentive structure of business journalists. Look through the prize-winning Loeb and Pulitzer stories, and you won’t find a lot of positivity. Most of the time, the professional plaudits go to writers who expose fraud and dissect disaster, rather than those who celebrate recovery and right-thinking. (The exceptions are writers like Daniel Gross, whose book Better, Stronger, Faster is a delightful paean to positivity.)

But it’s hard to endorse Blankfein’s view that the economy is hobbled by pessimism, if only because it comes from Blankfein.

After all, Blankfein’s world does look pretty sunny compared to that of the average American. Unlike millions of Americans, Blankfein kept his job and his house throughout the recession. His firm is profitable, and he has been paid at sky-high levels every year since the crisis. (Last year, he earned $21 million — or roughly 420 times the national median household income.) And most of his C-suite brethren have done well, too, with corporate profits at an all-time high, even as worker wages stagnate.

Goldman Sachs alone didn’t cause the financial crisis, but it helped. And the bank weathered the crisis remarkably well, thanks to a bailout of AIG, the taxpayer money it got from TARP, and a right-way bet on the housing collapse. (It’s even arguable that Goldman gained an advantage from the crisis, in the form of dramatically weakened rivals.) So yes, when viewed from the top of a Wall Street bank that is now making as much money as it did before the crisis, all of this doomsaying might look a little melodramatic.

But when Blankfein calls for positivity among the rest of us, he’s forgetting exactly how bad the country was burned by the crisis. It’s understandable that Americans would have a little bit of economic PTSD just five years after a recession that cost the country $15.6 trillion in household wealth, erased 7.5 million jobs, and created an incredible amount of long-lasting pain and misery.

The kind of disruption the Great Recession caused can’t be forgotten in a few years. It’s a generational affliction, one that was destructive socially as well as economically. It created cynicism and made many Americans hesitant to take good news about the economy at face value, especially when that news comes from the same financial system that couldn’t see the last crisis coming. The caution people now feel about spending their money isn’t irrational. It’s a direct result of having had the rug pulled from under them in 2008 and 2009, and not wanting to fall into the same trap again.

It’s understandable — and maybe even empirically correct, given the amount of heartening data out there — that the CEO of Goldman Sachs wants to break America out of its economic insecurity. But from his privileged perch, he should also try to understand why most Americans aren’t ready to sound the all-clear just yet.