The Republican postelection ideological repositioning project has chugged along fitfully and without satisfaction until just recently, when a solution struck with the blinding force of revelation. The concept is to define the Republican Party as the populist opposition to the Obama administration. Obama, goes this line of reasoning, is not the advocate of the people he puts himself forward as but the defender of bien-pensant elites. Republicans are — or should be — the party of stripping the elites of their government favors.

Timothy Carney and Ben Domenech have called this notion “libertarian populism.” Ross Douthat, after initially offering a measured critique, has formulated his own version, which aspires to define the GOP as the “country party,” in contrast to the Democrats as the “court party.” Paul Ryan adviser Yuval Levin takes Douthat’s concept as tablets from Mount Sinai, urging co-partisans far and wide to heed its wisdom. In a sign of the speed with which this new message has conquered the party, Ryan plucked it for his official response to Obama’s economic speech:

But the ease with which the party has converged on this line of thought also suggests something else: that the new populist emphasis doesn’t challenge any core elements of the Republican liturgy or, indeed, commit the party to any particular course of action at all.

The most important premise of Republican populism is the belief, accepted as self-evidently true after four and a half years of relentless repetition, that Obama’s governing style is corrupt, or at least close to corrupt. Obama’s agenda, writes Carney, amounts to “taxpayer transfers to the big companies with the best lobbyists, with some crumbs hopefully falling to the working class.” Douthat calls it “cronyist liberalism.”

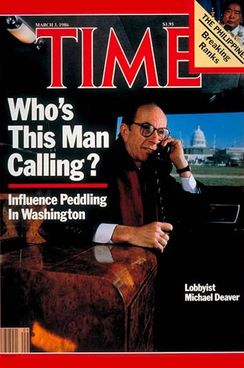

But this is almost completely wrong. There’s a speck of truth here: Obama has fallen short of the soaring idealistic vision of governance campaigned on in 2008 — negotiations conducted on-camera, lobbyists treated in his administration like lepers — but he’s still easily surpassed the normal presidential standard of good governance. The Bush administration devolved into a massive K Street patronage operation; Reagan’s administration featured five distinct genres of corruption scandal (sixteen Reagan HUD staffers were convicted of bid-rigging, high-level staffers Michael Deaver and Lyn Nofziger were convicted of illegal influence peddling, Reagan’s EPA was a sewer, etc.).

Obama has negotiated, compromised with, and in some cases co-opted business interests. But the indictment of his agenda as unusually or fundamentally cronyist rests on a weirdly hyperbolic aversion to the public sector when it comes to advancing liberal goals. Most government functions, unless designed in the most socialistic fashion possible, are going to involve hiring private business. Obama’s goals of reducing carbon emissions or providing medical care to the poor and sick will thus necessarily create new business for insurers, hospitals, green-energy firms, and so on, while also threatening others.

When it comes to public functions like, say, border security or national defense, conservatives accept this as normal. Under Obama they have blown it up into “crony capitalism.” Now, it is crony capitalism when the government uses its relationship with business in a slanted or political way, subverting its stated policy goals for political or financial profit. But Obama hasn’t had a whiff of any such scandal. The stimulus, which conservatives predicted would devolve into a slush fund, was carried off almost spotlessly.

Solyndra is the crown jewel in the crony capitalism indictment, and Mitt Romney used it last year as a synecdoche for Obama’s alleged crony capitalism. In reality, Solyndra is a non-scandal — lots of green-energy firms received federal loans on a fair competitive basis, and Solyndra happened to go bust. Even Darrell Issa had to admit it involved no political string-pulling or favoritism at all. And the apparently forgotten fact that Romney did run against “crony capitalism” shows how easily the “court party” or “libertarian populist” analysis can be harnessed to an unreconstructed Republican agenda.

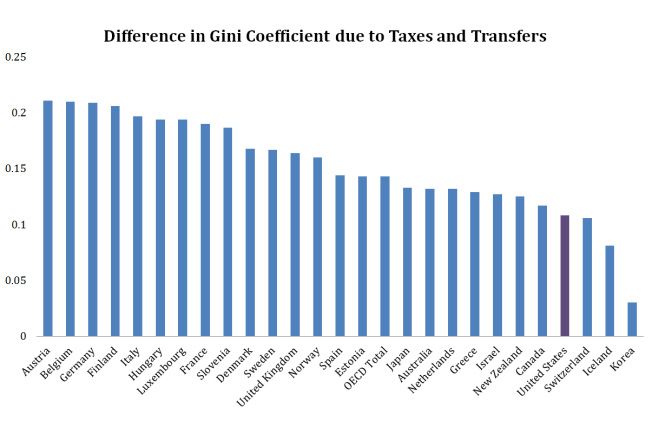

A second mistaken premise of Republican populism is a confusion over what causes inequality in the United States. Republican populists are obsessed with the role of elites using the government to reinforce their privilege. Certainly examples of this exist. But the main driver of inequality today is the marketplace, and the main bulwark against that inequality is the federal government. The federal government disproportionately taxes the rich, and it disproportionately spends on the poor. Our government redistributes less from rich to poor than do most other advanced countries, but it does redistribute:

In the face of this, a populist Republican faces two options. One is to attempt to meld the populist impulse with economic libertarianism, by devising an agenda that shrinks government exclusively in ways that do not increase inequality. You can see this in Carney’s heroic efforts to craft an agenda out of such items as abolishing the Export-Import Bank, eliminating the ethanol mandate, and reducing the payroll tax. I don’t mean to ridicule — there are real things to do here. But you could eliminate every business subsidy in Washington, and you’d still have in place a massive income gulf and a wealthy elite able to pass its advantages on to the next generation (through proximity to jobs, social connections, acculturation, spending money on education) that have nothing to do with government. The egalitarian laissez-faire economy is a fantasy.

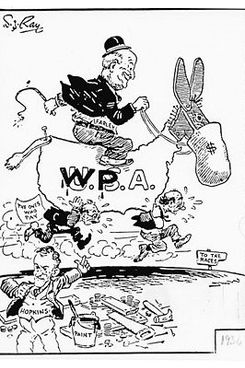

Some Republican populists don’t shrink from this reality. By their way of thinking, market outcomes are inherently just. “Unfairness” is something the government creates by definition. This is what writers like Domenech (“the cause of limited government as a means not only to safeguarding liberty, but to unwinding webs of privilege and rent-seeking”) or Levin (“Capitalism is fundamentally democratic”) are getting at. But this is not a new idea at all, merely a new label for an old conservative tradition of attacking welfare queens or New Deal goldbrickers.

The commonality tying together both of these errors is a failure to acknowledge the actual class contours of the American political debate. The main thrust of American politics is fairly simple: Democrats want to redistribute resources downward, while Republicans don’t. The main battles of the Obama era have been over Obama’s plans to raise taxes on the rich and offer more generous benefits to the non-rich. The “crumbs” for the working class are, in fact, the main part of the Democrats’ domestic agenda.

Meanwhile, opposition to redistribution is the defining feature of the Republican Party, connecting its refusal to increase tax revenue on the rich, its crusade to deny Medicaid to the poor, and its revolt against food stamps. The political analogue is the GOP’s crusade to winnow the electorate in every state it has control.

Some conservatives, like Douthat, are substantively uncomfortable with the Republican anti-redistribution agenda, while most others are merely discomfited by the political optics of it. Pretending Democrats are actually succoring elites is a handy way for all of them to avoid grappling with the central issue.

If you define privilege as “privilege meted out by government,” then, ergo, the Democratic Party is the party of privilege — the court party, the elites. There is certainly room to flay the GOP for its deviations — its farm bills, its business tax breaks — while ignoring both the main sources of economic and social privilege in America and disposition of the two parties toward it. But the right-wing populist analysis is still a magic trick, a way of transmuting the party that taxes the rich to provide health insurance to the sick and poor into the party of the rich and powerful. Far from the basis for a realistic program for the Republican Party, it’s merely a form of self-deception.