The idea of a Comptroller Eliot Spitzer is interesting for many reasons — the inevitable Post headlines, the ready-made story of political resurrection, the opportunity for the masses to learn what the hell a comptroller is. But one of the most exciting things about Spitzer’s candidacy has nothing to do with prostitute puns or financial education.

It’s that Spitzer, if he wanted to, could finally muster the clout to make an easy fix to New York’s pension system that would save billions of dollars and make every firefighter, police officer, and teacher in the city who depends on a public pension better off.

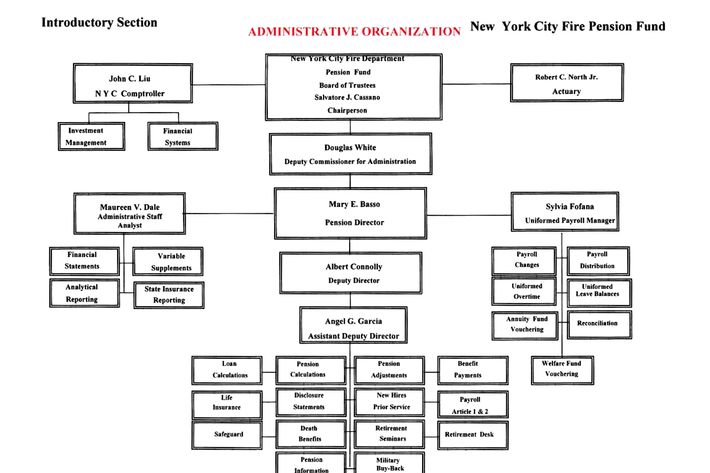

The fix involves restoring some order to the messy network of pension plans that currently exists in the city. Right now, there are five public city pensions — one for teachers, one for firefighters, one for police officers, one for Board of Education employees, and one for all other covered public workers. The comptroller is in official custody of all of these giant piles of money, whose assets currently total about $140 billion, but each of them is run independently. Each pays its own consultants, hires its own investment managers, and sits under its own board of trustees. There are about 60 trustees between the five pension funds and few professional investors among them.

It’s a terribly inefficient system and a bureaucratic nightmare. Just looking at the organizational chart from the firefighters’ pension fund’s most recent annual report (below) is enough to give you a headache.

Since all the pensions share a goal of maximizing returns, a much better solution would be to consolidate all five agencies under one roof, hire a world-class team of investors to invest the entire pool of money, and cut out a bunch of costs and red tape. Being a single $140 billion pension fund network, rather than a group of five smaller funds, would harness advantages of scale and allow the fund to negotiate for better fee arrangements with private-equity firms and other outside investors. And it would make it possible to attract investing pros to run the fund, rather than boards made up of union representatives and political appointees.

That’s exactly what current comptroller John Liu and Mayor Bloomberg proposed back in 2011. They estimated that the city could save $1 billion a year by merging its pension plans, hiring an investing A-team, and giving them control of the combined entity. Their plan was amazingly popular — even the union leaders liked it! — and it should have sailed through the state legislature. But after Comptroller Liu ran into a campaign-finance scandal, Liu’s opponents took advantage of his moment of weakness to attack the plan as a City Hall power-grab and turned union supporters against it. Their voices, added to the complaints of the consultants and other intermediaries who feared losing four-fifths of their New York pension business under a consolidated regime, effectively killed the plan.

The winner of the next comptroller race will have the chance to resurrect it. Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer, who is running against Spitzer for the seat, hasn’t made any promises about combining the five pensions, though he has promised to cut fees paid to outside managers. Spitzer could distinguish himself by making pension consolidation part of his campaign.

There is, however, a downside to combining the five plans into one professionally managed megapension. Namely, it removes the comptroller’s fiduciary duty and takes away a lot of his power. If Spitzer got elected and decided to give up control of the pensions, he might get better returns for the city’s retirees, but he’d be losing the chance to use the pensions’ investment portfolios as a tool for corporate reform. He’s said before that he likes the idea of pension controllers using their pools of money to advance political causes, and he’s already mentioned specific examples of how he’d wield New York’s pension plans as a bargaining chip with companies like JPMorgan Chase.

But Spitzer as comptroller would have other ways to influence Wall Street and corporate governance. And there’s no reason that the Liu/Bloomberg plan should wither away simply because Liu got wrapped up in scandal. Spitzer said this morning that he wants to “reenvision” the comptroller’s office. If elected, he could start by reviving the consolidation plan and using his political savvy to push it through. It’s not the sexiest campaign plank, but it’s one that would put the city’s pensioners on much firmer ground.