Detroit’s collapse into bankruptcy has been held up by conservatives as a synecdoche for America’s future under Barack Obama. In its literal sense, this is totally wrong — Detroit’s troubles are unique in their severity. In a broader sense, though, there is some truth here. Detroit is a synecdoche for America — not America’s future, but its past.

Everything that happened in the United States in the middle of the twentieth century happened in and around Detroit, but moreso. The enormous mobilization of industry during World War II (“Detroit is winning the war,” said Joseph Stalin in 1945); that industry’s creation of the world’s first mass-affluent working class, a place where families lacking high school diplomas routinely had nice things; and finally the collapse of that economic paradise and the racialization of American politics that split the New Deal coalition.

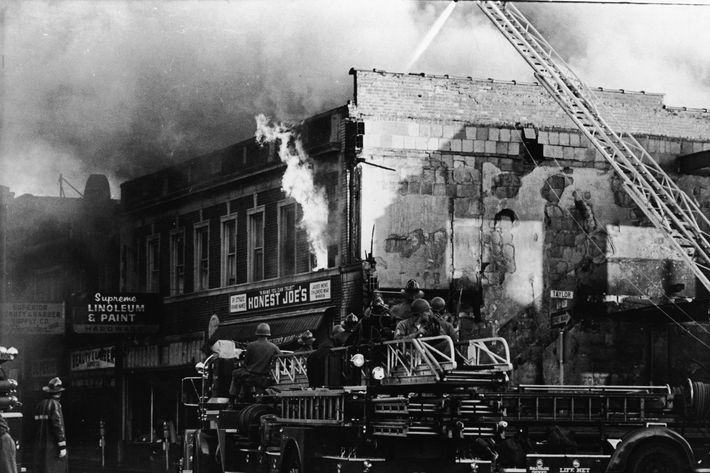

The 1967 riots were an event so traumatic they still hovered over the city when I grew up there in the eighties. The city burned down, and kept burning for years and years. The owners of its huge stock of abandoned, worthless properties would set arson fires, usually using the cover of “Devil’s Night,” a night-before-Halloween folk holiday of pranks and vandalism that as a kid I thought was observed everywhere but turns out to be mainly a Detroit thing. The city would have hundreds of fires of Devil’s Night, up to 800 a year at its peak.

Ze’ev Chafets, a native of the Detroit suburb of Pontiac, borrowed “Devils Night” for the title of his 1991 book about the city and its political culture. He compared Detroit to a liberated colony, whose politics was defined by continued resentment of the departed white occupier. White and black politics were locked into mutually reinforcing pathologies. Whites fled the city, blamed blacks for its destruction and, in many cases, gloated in its failures. Hostility toward the white suburbs shaped Detroit’s politics, which frequently amounted to race-to-the-bottom demagogic contests to label the opposing candidate a secret tool of white interests, with the predictable result on the quality of government. The worse Detroit got, the more whites hated and feared, fueling black racial paranoia, which made the city worse still. (Some national commentators recently suggested that Mitt Romney be brought in to turn around the city, which is a bit like suggesting that Benjamin Netanyahu would make a great Prime Minister for the Palestinians — hey, he’s from around there!)

In the mid-eighties, political scientist Stanley Greenberg traveled to Macomb County, a largely white, blue-collar Detroit suburb, which was also an epicenter of “Reagan Democrats,” who had abandoned the party. What he discovered was that these voters had come to see most all of politics through a racial prism. The Democratic message of economic fairness meant, to them, taking from whites and giving to blacks. Bill Clinton adapted Greenberg’s findings into a national persona — a “different kind of Democrat,” who was tough on crime, and who would “end welfare as we knew it” — that could rebuild a trans-racial Democratic coalition.

Detroit had one of the most racially segregated housing patterns in the country. I never recall hearing or seeing any expressions of anti-black racism, but this was probably because African-Americans were just so few on the ground. Paul Feig, who grew up in Macomb County, created Freaks and Geeks, a brilliant cult classic about a suburban Detroit high school in the early eighties, which captures the racial dynamic we experienced pretty well.

I grew up in Oakland County in the eighties. Many of my classmates’ parents forbade them from venturing south of 8 Mile Road, the Detroit city boundary, when they got their drivers’ license. Even those of us under no such restriction felt little pull toward the city. If you weren’t going to a Tiger or Red Wings game (the Lions and Pistons already having relocated to the suburbs), going to the city, going to Detroit was more an act of civic boosterism — charity, almost — than something you did for fun. It wasn’t, Let’s go to such-and-such, in Detroit!, but, Let’s go to Detroit! What should we do there?

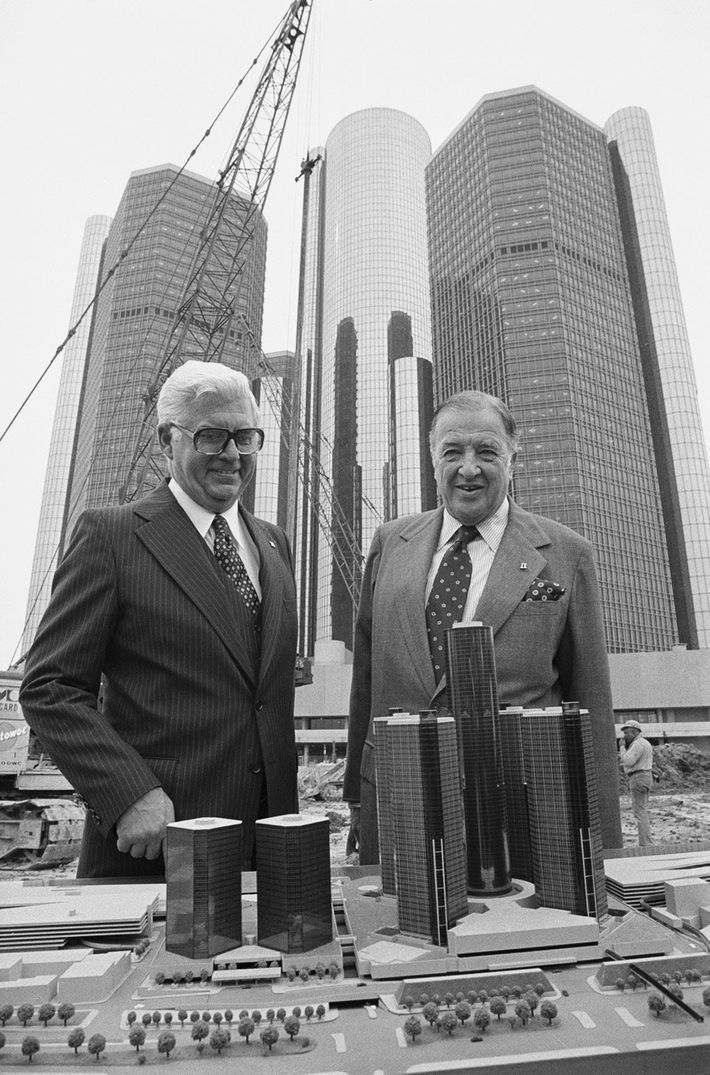

The city has been in decline for so long that its residents, or the suburbanites not cheering for its failure, always assumed it had to have hit bottom. Ten years ago, while visiting my parents, I attended an improv comedy show infused with booster-ish cheering for the city’s new mayor, who the actors celebrated half-ironically as “black Jesus.” It didn’t work out so well. The Renaissance center — the hoped-for catalyst for Detroit’s rebirth — started in 1971.

The bitter racial polarization of the seventies and eighties did not disappear, but it receded into the background. Jennifer Granholm, the governor of Michigan, elected in 2002, embraced a message of reconciliation. (“The only thing that should come between Detroit and Michigan is a comma.”) Barack Obama won Macomb County, prompting Greenberg to declare the epoch over. But the crisis of the city of Detroit itself only deepened. White flight had petered out by 1990 — virtually all the whites had left the city by then — but the flight of the black middle class only accelerated.

Detroit’s crisis began as primarily a racial problem, but it has long since ceased to be one. You simply can’t maintain a municipal economic base consisting mostly of very poor people, who can’t afford to pay much tax and who require high levels of government services. The functionality of government — its capacity to do basic things like light the streets, deploy firefighters and police, send ambulances — teeters close to anarchy. Compounding matters is the fact that Detroit was already one of the most spread-out cities in America at its peak, when three times as many people lived in it as they do today.

It’s hard to imagine any plausible way to pull the city out of its death spiral. New jobs would help, but there’s nothing compelling the workers who got those jobs to reside in the city. The conventional urban policy solutions never intersected with the reality of Detroit’s crisis. As Ed Glaeser points out, urban renewal centered on furnishing housing and transportation, both of Detroit had in excessive quantities. The city needed better governance and education. The major renewal project of my youth was the “People Mover.” It was initially conceived as a light rail project to connect the suburbs to the city, a massively expensive undertaking in a huge area with abundant freeways. It shrunk to a small downtown monorail loop. It became a stop on the downtown field trip, for suburban schoolkids — you’d visit the art museum, eat lunch in Greektown, ride a loop on the monorail, and pile back into the schoolbus. The People Mover operates at about 2 percent of its planned capacity. The People Mover is a relic to a time when it was possible to imagine a simple construction project could save the city. The sorts of solutions imaginative reformers contemplate today are vastly more radical.

Detroit is not the future of the United States. It is the residual wound of the rise and fall of postwar America, the place where the egalitarian economy was born, and it where also died.