At 6 a.m. on Friday, I wake up, fumble for my alarm, and roll out of bed. As I walk to the kitchen to brew coffee, I think to myself: I am a cipher. I exist nowhere. My enemies could not find me, even if they tried. These thoughts come to me not because I fell asleep watching The Bourne Identity or took too much NyQuil before bed, but because I’m psyching myself up for a very difficult assignment.

For the next 24 hours, I’m going to try to live completely surveillance-free. I will foil Chinese hackers and the NSA with encrypted texts and VPN tunnels. I will find ways to buy things online without giving away any personal information and communicate via smartphone without producing metadata. Also, I will wear a funny-looking hat with small lightbulbs in it that will protect me from being caught on camera. With expert help and a spy’s toolkit, I will attempt to stick to my normal routine for an entire day, but without leaving behind a trail of data for the government – or anyone else – to collect.

I got this idea a few weeks ago, when some friends and I were talking about what Edward Snowden’s leaks concerning the NSA’s PRISM program meant for the future of privacy. Now that we know that the government can access our phone records and snoop on our e-mails, our Facebook messages, and our Google searches, will any digital interactions ever feel private again? Is it even worth thinking about life outside the panopticon?

Years ago, people who asked these questions might have been written off as tinfoil-hat nutters. But now, even normal people have reasons to be paranoid. If you’re an investigative journalist, a corporate executive working on a sensitive deal, a member of a targeted ethnicity, religious group, or political faction, or merely a citizen who puts a high value on privacy, you’re probably already worried about the extent to which you’re being snooped on. In a recent poll, roughly half of Americans said that the NSA’s data-collection efforts violated their rights. And as technologies like Google Glass become widespread, the pool of interactions that aren’t captured and catalogued — by private companies, the government, or both — will shrink even more.

Last week, after a proposal to defund the PRISM program narrowly failed in the House of Representatives, I decided to test the borders of the surveillance state, by trying to leave it for a day. Several friends pointed out that I could simply go camping in the woods without my gadgets, or become Amish. But my goal is to make my surveillance-free day a relatively normal one. I don’t want to wear disguises, change my name, and live on the lam, as Evan Ratliff did for his 2009 Wired story. I want to get online, check e-mail and Twitter, use a smartphone, eat meals at restaurants, buy things at stores, and take public transportation, just like I would on any other day. I want to see if it’s possible to maintain some semblance of personal privacy without time-warping to 1950 (or 1650).

I begin my project by shutting off all the technology in my house that automatically collects or sends out data about me. It’s a horrifyingly long list. I can’t use my Jawbone Up band, which wakes me up, tracks my sleep, and counts the number of steps I take every day. I have to switch my iPhone to airplane mode, turn my iPad and my Kindle off completely, and unplug my Xbox, since it’s connected to my home wi-fi network. Just to be safe, I also cover the cameras on my laptop, desktop, and cell phone with snippets of electrical tape, since savvy hackers can gain control of them remotely.

So, after my morning coffee, I start surveillance-proofing my biggest problem spots: my laptop and cell phone. Every day, these two devices transmit millions of data points about me — where I am, who I’m talking to, what I’m shopping for, which animated gifs I’m looking at — to an armada of private-sector companies and third-party marketers. Usually, I accept these leaks as the cost of living a digital life. But today, I’m going to try to tighten the information spigot.

Hundreds of programs and apps have sprung up in the last few years to help people keep their data out of unwanted hands, and when I was planning my surveillance-free day, I enlisted the help of two cyber-security experts to help me sort through them all: Jon Callas and Gary Miliefsky. Jon is a professional cryptographer and the co-founder of a company called Silent Circle, which makes a suite of software that allows you to send and receive encrypted calls and texts. Gary is the executive producer of Cyber Defense Magazine, and the founder of a company called SnoopWall, which makes a suite of apps that prevent cyber-spying and eavesdropping.

The first thing both Jon and Gary told me is that if my goal was complete anonymity and totally untraceable communication, I was certain to fail. They suggested I set my sights lower — shrinking my surveillance footprint, instead of eliminating it.

“Are you going to be completely invisible from the U.S. government?” Gary said. “Never. But you can make it painful for them to find you.”

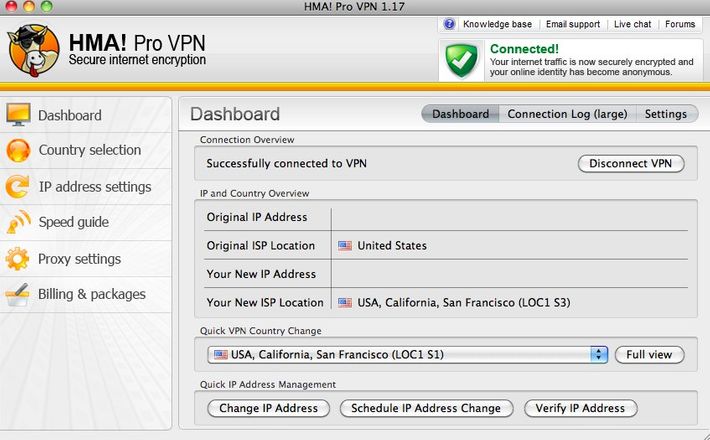

On their advice, I download Wickr, an app that allows you to send and receive encrypted texts and photos that self-destruct after minutes or hours of viewing. (It’s basically Snapchat on steroids.) I also sign up for a site called HideMyAss. It’s a private VPN service that is popular with the anti-surveillance crowd, since it allows you to camouflage your web activity by sending it through a network of thousands of proxy servers scattered around the world. I’m in the Bay Area, but with HideMyAss, I can make it look like I’m logging on from Brazil or Bangladesh.

While signing up for HideMyAss, I run into my first glitch of the day. Since credit cards are a privacy no-no, I was going to use cash and a Visa gift card (which I bought with cash at my local 7-11) to pay for things. But HideMyAss won’t accept a Visa gift card unless I register it with a real name and address — which sort of defeats the point. I’m feeling hopeless, until I spot a “Pay By Bitcoin” option on HideMyAss’s payment page. Bitcoins are, in many ways, the ultimate underground currency. They’re even better than Visa gift cards, since they don’t involve a credit card company or a bank at all, and since they exist only as untraceable strings of letters and numbers.

Luckily, I have a little left over in my Bitcoin wallet from my adventures with the crypto-currency earlier this year. So I click over to Coinbase and send about $50 worth of Bitcoins over to HideMyAss for a six-month subscription, the shortest I could buy. Once I log in, HideMyAss connects me to a server in a city of my choosing (I pick Reykjavik, Iceland), shows me a little green box telling me my connection is now secure, and asks me how often I want to switch servers. I set it for 30 minutes — meaning that in half an hour, my virtual life will pack its bags in Reykjavik and head to some other exotic locale. My online identity will be putting dozens of stamps on its passport today, even if I never leave my dining room table.

Next, I sign up for Hushmail, a Vancouver-based service that provides free encrypted e-mail accounts. Gmail is obviously a no-go for the day – Google being a particularly aggressive data-collector and PRISM target – and Hushmail, though not perfectly safe (it has forked over user data to the Canadian government in the past), is miles ahead. So I set up a vacation auto-reply on my Gmail account:

Hi, I’m trying to spend today entirely free of surveillance. Since Google is known to be part of the PRISM program, I will be using more secure web services to communicate for the next 24 hours. If you need to reach me today, please contact me through my secure email account ([redacted]@hushmail.com) or on Wickr (secure texting app) at username: [redacted].

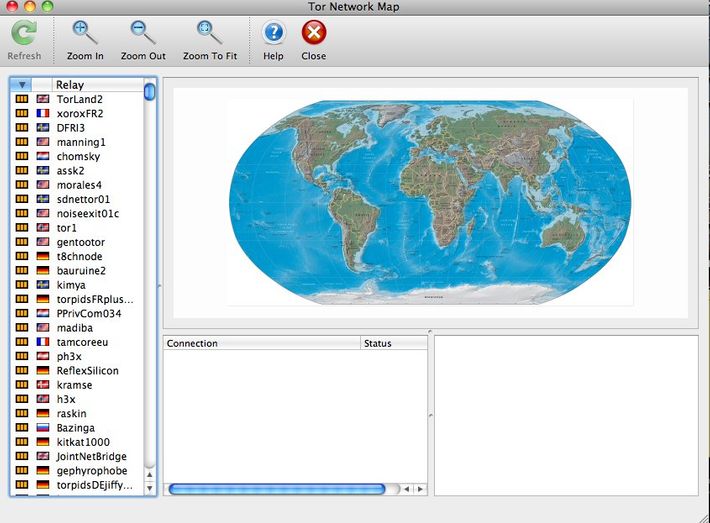

Once I’ve gotten HideMyAss and Hushmail running, I download Tor, a secure browser that is beloved by the hacker community. Tor (short for The Onion Router) works by shuttling your requests through a network of servers all around the world, and decrypting and re-encrypting data multiple times during transmission. It’s not a perfectly secure network, but it does a fairly good job of keeping its users anonymous – which is why it’s reportedly the browser of choice for cyber-criminals and online drug dealers.

While Google, Facebook, and Instagram are off limits, I carve out an exception for Twitter — sending direct messages over a secure connection, and posting public updates with no geotags — since the company isn’t part of the PRISM program and is known for fighting hard to maintain its users’ privacy in court. And I allow myself to log into my work e-mail remotely, since I think (hope?) my employer would never give me up to the feds.

Then there’s the question of what to do with my iPhone. It’s got all kinds of geolocation functions enabled (to tell me where my nearest Uber car, Seamless delivery restaurant, or ATM is), and it’s on a Verizon Wireless plan, which means that its metadata is being delivered to the NSA on a silver platter. To minimize my digital traces today, I’ll keep it on airplane mode and will only be using it for Wickr messages when I’m on a public wi-fi network — meaning that location services and cellular data functions will never come on. For all other things, I’ll use a burner phone – a Samsung Galaxy that was sent to me a few weeks ago as a tester unit, and isn’t registered under my name or connected to any of my existing accounts.

To avoid the risk of unwanted transmission, I decide to put both phones in a so-called “Faraday cage,” a conductive metal enclosure that will block out any radio or cellular signals. A video I found online claimed that metal cocktail shakers make the best Faraday cages, but my cocktail shaker isn’t big enough to hold two phones, so I wrap them in aluminum foil instead.

In all, I’m doing what most security experts would consider a half-assed job. I could protect myself much better with CIA-grade technology, and my plan is full of holes (for one thing, I don’t have a burner laptop). But the modern surveillance state is so pervasive that there are always going to be weaknesses in any amateur plan.

My favorite anti-surveillance hack of the day has nothing to do with either my phone or my laptop, though. It’s a red baseball hat that I outfitted with infrared LEDs, and wired to a pair of 9-volt batteries, following instructions I found online. Most surveillance cameras operate on the infrared spectrum. And to the naked eye, my hat’s LEDs will look like nothing. But on infrared cameras, they’ll drown my face and render me unrecognizable. I’ll just appear as a ball of light.

Both Jon and Gary pointed out one of the central paradoxes of my day – that, by downloading Tor and HideMyAss, by paying for software in Bitcoin, wrapping my phones in foil, and by turning my head into a giant glowing orb, I’m effectively asking to be put on a terrorist watch list. It’s the digital equivalent of hanging a big “I’M SKETCHY” sign around my neck. And as I browse through my morning news sites, using my Icelandic internet connection and my Tor browser, I can’t shake the feeling that black helicopters are already circling overhead.

Still, I have to keep going. I’ve got a full day ahead of me – some writing at my local coffee shop, an afternoon of meetings in San Francisco, an errand or two in the city, and drinks at a friend’s house after work. And somehow, I’ve got to do all of this while staying below the government’s radar.

And so, after finishing my breakfast, I get dressed, put some extra foil and batteries in my bag, don my anti-surveillance hat, and head out into the wide, watching world.

[For more of The Surveillance-Free Day, click here for Part II]