Steve Ballmer, Microsoft’s screamy CEO, announced today that he will retire in the next twelve months, after a successor is picked. The market cheered the decision, and shares have climbed 7 percent on the news.

It’s easy to see why. The list of Ballmer’s product follies runs fairly long and includes (but is surely not limited to) the Zune, Vista, Windows 8, Kin, and the Surface. (There’s also this opposite-of-prescient quote, from 2007: “There’s no chance that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share. No chance.”)

But while Apple might be chuckling at having proved Ballmer wrong on that front, it should also be worried. Because the same thing that happened to Microsoft under Ballmer’s watch could well be happening at Apple.

Ballmer and Apple CEO Tim Cook are cut from similar cloth — both are operations guys who were thrust into leadership roles after the departure of charismatic, visionary founders. Both enjoyed early praise and dealt with nagging questions about whether they’d be able to match their predecessors’ records when it came to innovating. Both trotted out new versions of flagship products developed under the old regime, enjoyed a steady inflow of cash from those franchises, and used that cash to play around with various new products.

Some of Ballmer’s early products were successes — the Xbox, released a year after he became CEO, revolutionized the video-game industry and brought Microsoft pop-culture credibility. But more of them were uninspired duds — ham-handed attempts to copy popular products made by other companies or cash in on emerging market trends. Ballmer took risks — acquiring Yammer, for example, or opening retail stores. But they were risks only in the sense that most people were advising against them. There were no flashy flameouts — no radically different products, no head-scratchers that took consumers by surprise. And the result was a timid company that always seems a few steps behind.

Right now Apple has the kind of wind at its back that Microsoft did when Ballmer took over in 2001. The iPhone is losing market share, and iPad sales are slowing, but they’re still profitable enough that Tim Cook could do nothing but release new iPhones and iPads every two years and his company would remain one of the largest in the world, with a twelve-digit cash pile and a stable stock price.

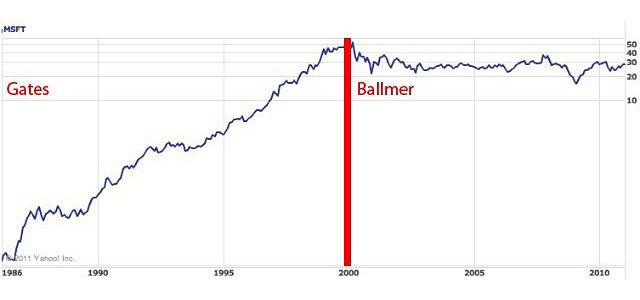

But cushions wear thin. And like septuagenarian rock stars, an aging tech company can only ride the old hits for so long before the audience gets impatient. Here’s what happened to Microsoft’s market cap after Ballmer took over:

And here’s where Apple is, with Tim Cook’s August 2011 appointment at roughly the halfway point in the chart:

Despite the obvious biographical parallels, Cook has some advantages over Ballmer. Whereas Microsoft was battling both Apple and Google, as well as larger industry trends (namely, the shift from desktop to mobile computing), Apple is on the right side of the mobile divide and has its best talent in its core iPad and iPhone divisions, unlike in Microsoft’s case, where the creative geniuses have been mostly sequestered in the Xbox unit.

But Apple has real threats too. The most obvious two are Samsung, whose mobile phones are gaining ground on the iPhone, and Google, which has decimated iOS’s market share with Android and is trying to upend Apple’s laptop sales with its Chromebooks. And unlike Microsoft, Apple’s core customers are finicky, impatient consumers, not businesses — which are generally slower to jump between technological platforms, given the hassle and expense it entails.

Tim Cook has so far taken the Ballmerian approach to innovation — releasing gold iPhones and the iPad mini, both tiny iterations on Jobs-era hits, and testing the appeal of quirky device categories like computerized watches.

That’s fine for now. But if Cook wants to keep Apple out of decline, he’s got to be willing to look stupid. As Ballmer’s twelve-year tenure has shown, when you’re a tech giant, it’s better to attempt big, bold things and fail than have your company die by a thousand small, boring cuts.