Alas, poor Gus, I knew him. A little.

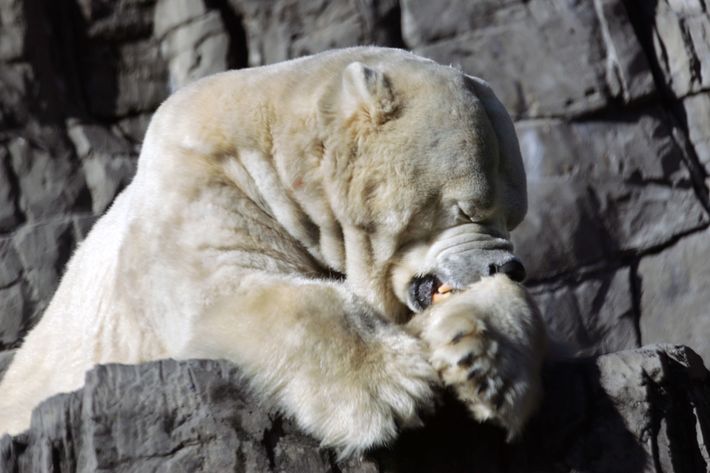

On Tuesday, the Central Park Zoo euthanized its 27-year-old polar bear, Gus. Veterinarians had discovered an inoperable tumor in his thyroid. He had beaten depression, and then beaten the actuary tables. Within the narrow category of New York City polar bears, he stood alone.

One summer, ten years ago, I had the privilege of working with him — or anyway near him. I used to walk past him every morning and every afternoon on my way to and from my job as a keeper at the Central Park Children’s Zoo. I wasn’t entrusted with anything so fearsome as a polar bear, reasonably enough; I was in danger only of being snuffled by a pig or spat on by an alpaca.

But I — like everyone else who worked at the zoo — held the polar bears in special esteem. They were our mascots, our stars, the animals that kids wanted to know about. Their exhibit was where you went on your lunch break if you found yourself wondering why you hadn’t taken a job in a law office.

And Gus, I learned from the keepers who actually knew what they were doing, was not just any polar bear. He was Gus the compulsive swimmer, Gus the bear with the $25,000 therapist. He had gotten famous in the nineties for his emotional problems — he had been bored and restless, neurotic and obsessive, and so the zoo had brought in a specialist. Needless to say, identifying with a gloomy male of 20 or so years did not require Shakespearean flights of empathy on my part. If my summer thus far had needed an epigraph, this line from a 1994 Times article about Gus’s troubles would have done perfectly: “ … an animal fills the void by doing exactly the same thing over and over again without any real reason.”

What Gus’s therapist had prescribed for him, I learned, was Enrichment. Enrichment happened to be my favorite time of day in the Children’s Zoo, since it offered relief from the security-guard-esque standing around that makes up most of a zookeeper’s day. (Most of a bad zookeeper’s day, I should clarify.) In the Children’s Zoo, Enrichment meant presenting the goats with a trash can smeared with peanut butter, or dangling keys at the end of a broomstick in front of the cow. The goats would knock their heads around the inside of the can and emerge giddy, peanut butter drunk.

But for Gus? Enrichment seemed beneath him, somehow, with his majestic swimming, his regal lazing, his terrifying paws. What were traffic cones or mealtime “challenges” to him? He seemed more the type for moody journaling, or stoic silence. Except that it had helped, apparently. The Gus I met was, by all accounts, a great deal happier than the Gus of 1994, and he remained quite happy, surrounded by toys slathered in peanut butter, for many years after.

This did not, although it should have, teach my anything.

Here were some of the things that were not doing me any good that summer: thinking, worrying, hoping, waiting.

And here were some of the things that were doing me good: running, shooting baskets, tinkering with the piece of writing that would, in time, become my first novel.

What I was doing when I was happy, although I didn’t realize it at the time, was acting out my own haphazard course of Enrichment. And I don’t, by comparing myself to a zoo animal, mean any insult. We humans, just like the animals in our zoos, were born into bodies whose workings are both mechanistically predictable and unfathomably complex. Put in lots of sugar and we’ll get fat and sick. Confine our movement and we’ll get weak and antsy. Give us some manageable problems with which to grapple and we’ll cheer up.

I didn’t understand it this way at the time, but to write a novel is to undertake just such a manageable problem. It is, like extracting that last little bit of peanut butter from the inside edge of the jar, just difficult enough to require your full attention, and just doable enough to keep you from despair.

The value of such tasks is a lesson, belatedly, that I’ve tried to apply to my own life — intelligence is not the same as wisdom. A container of peanut butter is not any less valuable than a container of bon mots. A bear-size unhappiness can sometimes be addressed with something as simple as a key ring.

We might all, in other words, do well to hire inner zookeepers, in addition to our inner critics and therapists and philosophers. Gus may not have known what to do about his misery, but neither did he know the myriad of human tricks for prolonging it. I hope, as he settles in on the great iceberg in the sky, finally reunited with his beloved Ida, that Gus is happy, and busy, and fully enriched.

Ben Dolnick is the author of the novel At the Bottom of Everything.