It’s been nearly two decades since Robert Reich held political office as Bill Clinton’s Labor secretary. Back then he was considered an affable moderate, capable of reaching across the aisle, but his steady pounding of the drums of middle-class neglect and income inequality in the years since as a cable TV pundit and Berkeley professor with 155,000 Twitter followers have made him into the kind of radical who is persona non grata at Fox News.

Reich’s newest project is a semibiographical documentary called Inequality for All — “An Inconvenient Truth for the middle class” is his pitch. The film was good enough to win at Sundance, pick up national distribution, and, on September 27, will begin playing in 40 cities nationwide. It imitates Al Gore’s global-warming shockumentary mostly in form — PowerPoint slides interspersed with taped tidbits and confession-cam pronouncements from Reich. Most of the facts and figures in the film aren’t new, but it presents a very tight and compelling sequence of very depressing statistics that turn out to be oddly empowering. Although Inequality for All is light on villains — Reich’s preference being to demonize ideas rather than individuals — you do come away from a viewing wanting to take to the streets, somehow, for something.

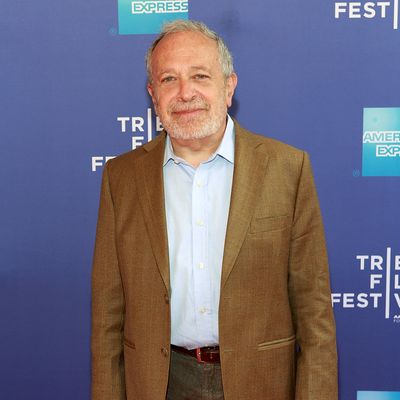

I met with Reich in his Berkeley office just before the start of the fall semester — he’s preparing to teach a big lecture class on public leadership, and bits of other courses — and we talked surrounded by piles of books and framed photos of Reich with Clinton, Obama, and other world luminaries, the kind that come with personalized messages inscribed to “Bob” in permanent marker.

Have you been happy with turnout for the movie?

I’ve been to about eight screenings, and most of them are getting standing ovations and great questions. But frankly, I don’t know what to expect. I’ve never made a movie or been part of a movie before. It’s unusually wide release for a documentary. But again, I have no relative judgments.

How involved were you in the process? Did you make the slides? Choose the music?

I didn’t realize when we started that [director] Jake [Kornbluth] was going to use me, and my life, as a sort of template. Because the years coincide with the years I was active in government and writing and all of this stuff. And I was a little bit uneasy with that. I didn’t want it to be a documentary on me. But he convinced me that it was important, I guess like Al Gore’s movie, that there was enough of me in it to make an emotional connection.

And then I still didn’t let myself think it was real until we got accepted into Sundance. Then I quickly learned that that was a big deal.

I confess that although I liked An Inconvenient Truth, it didn’t seem like it was going to convince anyone who wasn’t already predisposed to share Al Gore’s views on global warming. Do you think your movie can convert skeptics?

I don’t think this movie is going to convert anyone whose mind is already made up. But there’s a vast middle section of people who don’t understand the issue. That is, they know inequality is widening, and they know it’s been widening for many, many years, but they don’t understand why.

So, maybe the person who is casually interested in economics, or went to one Occupy rally.

Or a tea-party rally!

You really think a tea-partier is going to watch a movie about Robert Reich?

Well, remember, the tea party and Occupy Wall Street came out of the same Wall Street bailout. They came out of the same feeling that the dice were loaded against average people.

The movie doesn’t really pick fights. It looks at the system. Some people are a little bit nonplussed. That is, they came into the theater thinking there were villains and they wanted an exposé of villainy. In fact, if the movie says anything, it says this is the way we’re organized, and there are certainly people who have more principle and less principle, and we’ve blown it over the last 25 or 30 years, but it doesn’t take the easy way out. It doesn’t say, “Here are the bad guys — get them out of their positions of influence and we’ll be fine.”

My colleague Benjamin Wallace-Wells just wrote a story about the economist Robert Gordon, who calls the period of prosperity we’re in now, basically, a historical accident. Gordon says, Okay, we had a couple industrial revolutions that made us more productive; we had two World Wars that threw the economy into high gear; we had women in the workplace, which was an easy way to double productivity, but now we’re reverting to the mean. I found the argument pretty thought-provoking.

Well, he’s talking about productivity growth. Basically, economic growth comes from two sources — population growth and productivity growth. Now, there’s an interesting debate over whether technology is going to continue to generate growth. I don’t see any reason why not. There are plenty of people who think we’re on the edge of technical frontiers in materials technologies, biotechnologies, even more digital technologies. But I think the interesting questions are less about productivity and more the political and economic questions about who gets what and how to sustain our present path if more and more of the gains are going to fewer and fewer people. I don’t think that’s sustainable.

So, your retort to Gordon would be that even if the pie is shrinking, there could be a better allocation of that pie?

One of the reasons the pie has stopped growing so fast is because you don’t have adequate demand, and one reason you don’t have adequate demand is that the middle class and the poor don’t have nearly the purchasing power they had before. And yet our productivity keeps increasing, so your potential pie grows, but in terms of buying that pie …

When you look at places in America that are experiencing economic booms, it’s places like Texas and North Dakota, that have huge energy reserves, and Silicon Valley, where people are getting wealthy off of technology ventures. Is that sustainable?

Look, a natural-resource-based economy can take you only so far. If you want sustainable growth, you have to have a wide portfolio of economic activities, and you have to have enough indigenous demand to sustain your economy. If you’re relatively small as a country, yes, you can rely on exports. But reliance on exports is a little dangerous. Even China realizes it’s got to somehow move to a consumer-driven economy.

So you’re not calling for an American manufacturing renaissance?

People who call for one don’t really understand what they’re talking about. You look inside a manufacturing company today, and you don’t see labor-intensive assembly lines. You see robotics. There are advantages to having manufacturing here, but the advantages are all for small suppliers, not just of parts, but also of services.

What’s happened in the U.S. over the last 35 years is that we haven’t figured how to nurture small feeder companies. But more importantly, we got lazy. We rested on the successes of the first three decades after World War II, and we didn’t face for years the reality of stagnating wages.

Why not? Because GDP was going up and up?

Sure, GDP was going up. But also, we found a variety of ways to keep ourselves going without having to face stagnating wages. One was putting women in the workforce … that was the first coping mechanism for the middle class, in terms of keeping up its standard of living when wages weren’t growing. The second coping mechanism was everyone working longer hours. And then, finally, we borrowed against the rising value of our homes. Now the interesting thing is that every one of those coping mechanisms is now exhausted.

So what do people do? Is there a way to increase wages systematically without the kind of robust labor movement we had in the middle of the twentieth century?

Well, you need to expand the Earned Income Tax Credit, which is the biggest anti-poverty program that nobody knows about. Two, health care is very important; you have to get everyone into it. Three, child care. There is a huge cohort of people for whom that second wage earner is spending 60 percent of her earnings on child care. Fourth, education. Fifth, you need some sort of progressive tax reform. And sixth, I think it’s important to unionize low-wage workers. Big-box retailers, fast food, people involved in health care.

What American company is doing a good job? What’s the examplar?

I don’t think there’s one example. Costco, for example, pays its workers, trains its workers. As a retail force, they are earning much more than other retail workers. There are other companies — Kaiser [Permanente], in terms of health care, that give very good training and wage benefits to their workers. Hmm … let’s see. I’m trying not to include a high-tech company. If you go into high-tech and finance, they’re all treating their workers wonderfully because they want to hold on to them.

What’s your relationship with Elizabeth Warren like these days?

I admire her. I have worked with her. And I’ve helped her with some campaign events. I think very highly of her.

Do you support her Glass-Steagall 2.0 push?

I haven’t seen a very subtle analysis of that particular bill. But I do think Glass-Steagall needs to be reinstated. I think it was a shameful day in the Clinton administration when the White House decided to sign on to getting rid of Glass-Steagall. But even if Glass-Steagall is resurrected, that’s not going to make Wall Street more responsible. I think we need to use the antitrust laws to limit the size of the big Wall Street banks.

Do you spend a lot of time talking to people on Wall Street? How regular is your communication with financial-sector types?

Pretty regular. It’s hard to avoid them in Washington. For example, Bob Rubin, whom I consider a friend even though we locked horns the entire time I was in Washington, but that doesn’t mean I can’t like him. But there is a Wall Street worldview that is very distorted by money, and by concentrated power. I don’t think Wall Street has the faintest idea of what’s happening outside Wall Street and Manhattan to average working people.

Do you think Silicon Valley is more aware of the world outside itself?

Silicon Valley isn’t quite as insular yet, but it’s moving in that direction. At least Silicon Valley is producing services that people want to use. If a new app doesn’t catch on, Silicon Valley is getting some important feedback. But Wall Street is operating in its own bubble regardless of what most people want.

Berkeley is, you must admit, something of a lefty bubble. Do you find you have the opposition you need?

I go around the country a lot, so I come up against a lot of opposition. Even in airports, people who have seen me on Kudlow or MSNBC say, “Let me talk to you about that,” because I’m fairly conspicuous. [Gestures to his head and laughs, a reference to his four-foot-eleven frame.]

Also, Berkeley is the most unequal distribution of income of any Bay Area community. Did you know that?

No.

That’s a credit to Berkeley. It means that Berkeley has kept the rich, the middle class, and the poor all in Berkeley. That’s very hard to do. Mostly you have cities that are all rich or all poor.

So, I must ask: Mayor Bloomberg. Your verdict?

He’s had an impressive run. He’s shown a lot of guts. Now, some people might say it’s easy to show guts if you’re that rich. But look, he’s an example of someone who has a great deal of money who didn’t have to take on what has been historically a very thankless job. I give him a lot of credit.

One thing that occured to me as I watched the movie is that you say that Fox News never invites you on these days, whereas you used to be a frequent guest. Do you miss having a seat at the table? Being able to speak to both sides?

I’m never asked on Fox, and I very rarely have an opportunity to speak to conservatives. That’s different than what it was ten to fifteen years ago. And I haven’t changed.

The left has become slightly more left, but the right has gone quite far to the right. I mean, you’ve got Republican members of the House and Senate who are openly looking for ways to impeach President Obama. I don’t remember it that way.