Every September, we financial writers commemorate the anniversary of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy by wringing our hands over the question “Has Wall Street changed since the crisis?” The answer is always “No, not really,” and the reasoning is usually the same: no CEOs in jail, no big-bank shrinkage, no full implementation of Dodd-Frank, more dangerous shadow banking and illiquid derivatives and whatnot.

Many of these points are quite valid. But the overbroad conclusion they’re often used to make — that the financial sector is no safer or wiser today than it was when Lehman collapsed — is ludicrous. The truth is that Wall Street has improved enormously since September 15, 2008. Those saying otherwise are letting cynicism cloud their perception.

To see why Wall Street 2013 is superior in all ways to Wall Street 2008, let’s look at a few of the oft-registered complaints about the last five years in the financial industry.

Complaint: Nobody on Wall Street has been punished for what happened.

This is the most frequent gripe about what’s happened since Lehman. (“No man or woman who led one of the firms directly culpable for the catastrophe has been put in a prison-orange jumpsuit,” Neil Irwin frets, in one of probably dozens of examples written this week.) And it’s true that the Jimmy Caynes and Dick Fulds of the world are free men, and that this fact is emotionally grating.

But focusing on the lack of individual cases — which, by the way, regulators wanted to bring very badly but decided they didn’t have sufficient evidence for — misses the forest for the trees. The truth is, the big banks have been punished for the crisis in the way that hurts them much more than jail time: on their balance sheets. They’ve spent a staggering $103 billion on lawsuits stemming from the crisis (more than their entire 2012 profits, Bloomberg notes), traded below their book values, and seen their returns on equity (a core measure of profitability) plummet so low that bankers are worried that investors will give up on them.

Nobody’s disputing that there were outrageous legal violations during the crisis, from robo-signed foreclosures to Repo 105 accounting shadiness. And some of these crimes went shamefully unprosecuted. But many were punished, in ways as big as a $51 billion mortgage settlement and as small as finding a midlevel Goldman Sachs mortgage guy liable for securities fraud. These penalties aren’t as cathartic as seeing a CEO do a perp walk, but they’re not nothing.

Complaint: The banks are still overleveraged.

This objection stems from the fact that capital ratios (a way of measuring the cushions banks have against losses) aren’t as big as some reformers would like them to be. As Anat Admati wrote in the New York Times last month: “We will never have a safe and healthy global financial system until banks are forced to rely much more on money from their owners and shareholders to finance their loans and investments.”

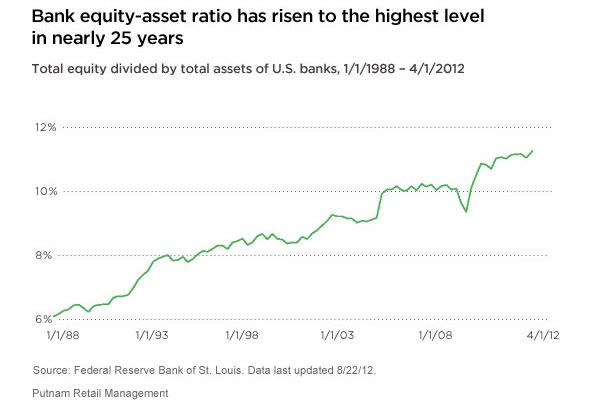

Admati is right about a lot. But she’s being overly cynical here. Banks are, in fact, much better capitalized than they were in 2008, thanks to Basel III and other standards put in place since the crisis. As the below chart shows, equity-to-asset ratios among the big banks are at their highest point in 25 years. Tier 1 capital ratios (a slightly better equity-to-asset measure that uses risk-weighted assets) are also high relative to historical norms. Even David Dayen, who doesn’t think Wall Street has changed much since 2008, concedes that “Dodd-Frank and Basel III have made marginal improvements” to the quality of banks’ capital structures.

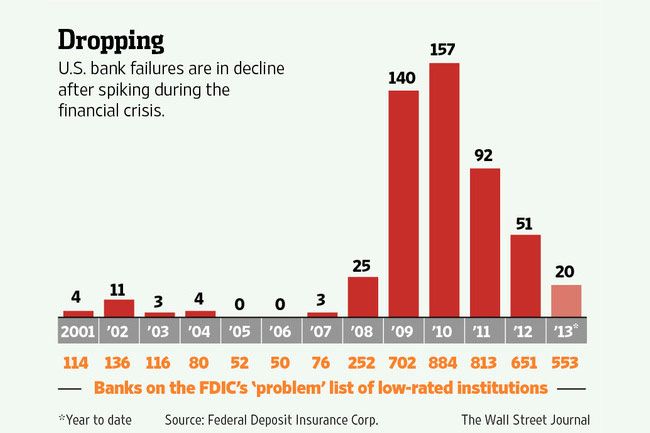

And look at how few banks are failing now!

This isn’t to say that the capital requirement boosting we’ve done so far is enough, or that Basel III is an adequate shield against future crises. Only that banks are much more intelligently structured than they used to be.

Complaint: There’s still too much risk in the financial system.

It’s true that, thanks to the Volcker Rule (which limited proprietary trading by banks) and other post-crash regulations, some of the risk that used to be contained in the banking system has been pushed into a lesser-regulated and more opaque shadow banking sector. But let’s focus on the banks. Does anyone really think that Citigroup and Bank of America are still taking the kinds of risks they did in 2007?

The Wall Street Journal had a good profile recently of Morgan Stanley CEO James Gorman, who has succeeded enormously in turning around that once-flailing bank by, in essence, making it boring. It’s now predominantly a retail brokerage rather than a trading dynamo. The same basic transformation has happened all over Wall Street. Portfolios are smaller; derivatives are more transparently bought and sold; and this summer, when two banks tried to package and sell a synthetic CDO — the same types of derivatives that brought down AIG and endangered the financial system — nobody wanted to buy. There is still risk in the financial system, but it’s not backed by the same devil-may-care attitude we saw in 2007. Even Neil Barofsky — the TARP inspector general and as pure a critic on regulatory matters as you’ll find — concedes that we’re safer now, though we have a ways to go.

Complaint: The too-big-to-fail problem still exists.

You may have heard that big banks have actually gotten bigger since the crisis. This is true in a strict sense, mostly because a bunch of mergers consolidated former rivals after the crisis. And it’s natural to worry that because these banks are so big, they’re backed by an implicit government guarantee of a bailout, should another crisis happen.

But I actually find the Treasury Department’s case on this point fairly compelling. Treasury points out, following Matt Levine’s example, that big banks have had higher borrowing costs than smaller banks since the crisis, meaning that investors aren’t taking it as a given that they’ll be bailed out in the event of trouble. The counterargument, that big banks are receiving a taxpayer “subsidy” in the form of depressed borrowing costs, simply doesn’t check out.

Of course, it’s impossible to know if too-big-to-fail exists without having it tested in practice. But I find it incredibly hard to believe that if another Lehman-like catastrophe happened, our lawmakers would find their continued existence a compelling enough reason to fork over billions of dollars.

Complaint: All the regulations put in place after the crash got watered down by bank lobbyists.

It’s true that as lawmakers have ratcheted up regulations on banks since the crisis, lobbying firms have been right beside them, trying to lighten the load for their bank clients. And it’s a disgrace, as Bloomberg News points out, that only 40 percent of the rule-making requirements in the Dodd-Frank Act have been met and that key pieces like the Volcker Rule have gotten held up by the financial industry’s protestations.

But if banks had gotten their way all along, there wouldn’t be a Dodd-Frank to water down. And the fact that these rule-making battles are being fought, rather than merely conceded to Wall Street straightaway, is a testament to the stiffer backbones of today’s regulators, and their willingness to argue for weeks over seemingly minor rule changes. The fact is that regulators have always been outmatched by Wall Street lobbyists, who have much more money and talent to throw at every picayune argument. For years, it wasn’t even close — the banks steamrolled Washington and got all the deregulation they wanted. Now it’s at least contested.

So, what am I trying to say?

Bear in mind: Saying that Wall Street is better than it was in 2008 does not mean that all is well. There’s still a lot of work to do to make the financial system safer, and we shouldn’t stop writing laws and trying to shrink banks and regulate derivatives more tightly, and all of the other reasonable measures that have been proposed by advocates of deep reform.

I’m not taking the banks’ side here. Really. And I wouldn’t go as far as Morgan Stanley CEO Gorman in saying that the chance of another crisis in our lifetimes is “close to zero.”

But pooh-poohing the progress we’ve made at reining in the financial system’s danger since Lehman only has the effect of entrenching cynicism, and making genuine reformers feel underappreciated. Wall Street is a long way from perfect, but thanks to the efforts of a lot of well-intentioned people and institutions, it’s a lot less of a threat to American prosperity than it was five years ago. And for that, we should give at least a little credit where it’s due.